In October, 1962, Toronto Daily Star writer Gordon McCaffrey reported that Metro Toronto was becoming a key target area in a massive invasion of Ontario (and Quebec) by U.S. drive-in restaurants. For the first time, through franchise agreements, U.S. chains were appointing Canadian companies to buy locations and lay the groundwork for restaurant chains to expand into Canada.

McDonald’s, Dairy Queen, and Kentucky Fried Chicken, to name a few, all arrived in Canada at this time. These chains are now standard fare. But many people have no idea that a drive-in franchise called “Aunt Jemima Kitchen” was also part of this American invasion.

As part of the Quaker Oats Company of Canada, Aunt Jemima Kitchen offered something different. While it served southern fried chicken, like KFC, it was neither a fast food chain nor a bar; it was branded as a family restaurant with full table service.

Scarborough was particularly favourable to U.S. chains, like Aunt Jemima Kitchen. By the early 1960s, the area had a high ratio of cars to population, the standard of living was good, and, as McCaffrey noted further, the community was having “growing pains” due to a lack of dine-in restaurants.

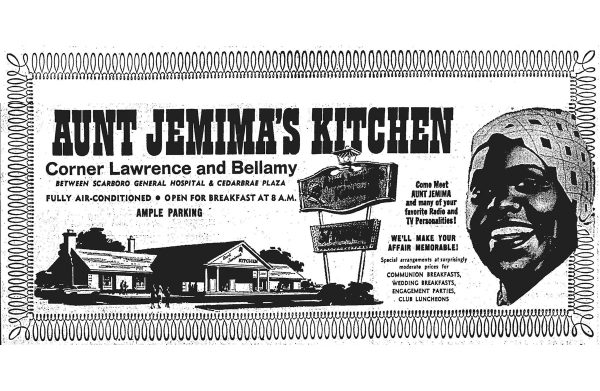

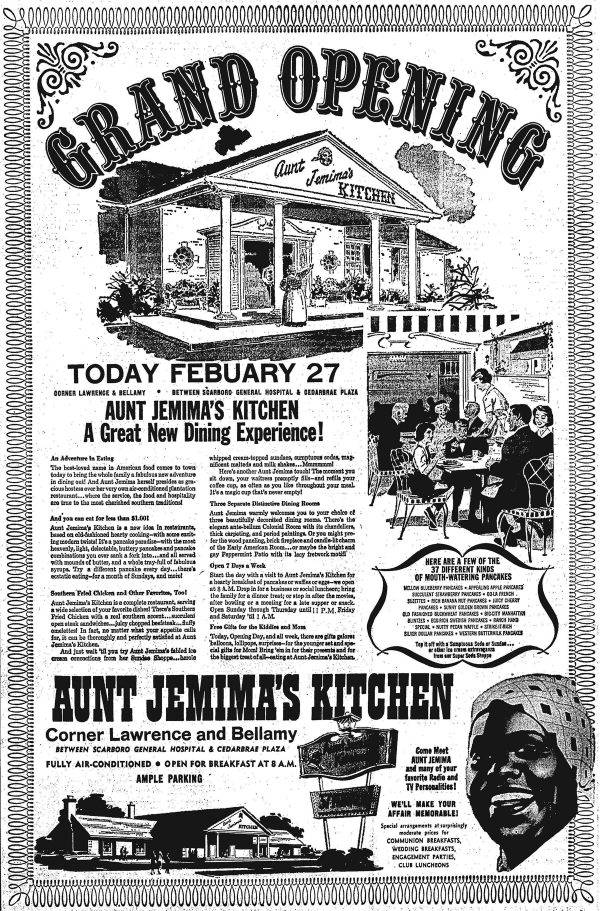

In February, 1963, an ad in the Toronto Daily Star alerted readers to the restaurant’s grand opening at the corner of Lawrence and Bellamy (a present-day KFC location), near Cedarbrae Plaza, which opened in 1962. In May, 1963, The Globe and Mail reported that Scarborough was to become a “test” area for more Aunt Jemima Kitchens, where customers would also meet a ”real” Aunt Jemima while they ate.

Many people love Aunt Jemima products. Some can’t imagine a pancake breakfast without the trusted syrup. Yet she was and remains an image of Black servitude that started in slavery.

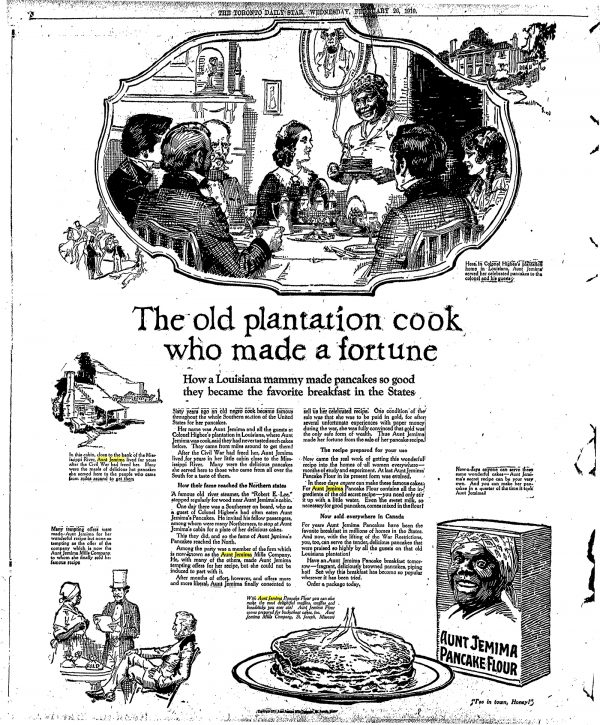

Descriptors like “mammy” and “Auntie” (along with “Uncle”) first appeared in antebellum fiction to describe both a person and a role within the southern plantation home. In her book, “Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory,” Kimberly Wallace-Sanders observes that Aunt Jemima offered northerners the southern antebellum experience of having a mammy, without actually participating in slavery. In this way, her popularity bolstered the romantic mythology of the southern plantation.

The use of “Aunt” in consumer culture began in 1889 when Chris Rutt, a St. Joseph, Missouri, flour-mill operator, produced a ready-mix pancake batter, which he sold without a name. After Rutt attended a minstrel show where a duo, performing in blackface and drag, sang a song and dance called “Aunt Jemima” while wearing an apron and a red bandana, he decided to use this image for his product. The “red-bandana-wearing Black woman as cook,” who personifies so-called southern hospitality, became Aunt Jemima.

In 1890, the Aunt Jemima trademark was sold to the R.T. Davis Milling Company, which devised a new marketing and promotional strategy around the product, including finding a real Black woman to perform as Aunt Jemima to bring the product to life.

While PepsiCo, which acquired the Quaker Oats Company in 2001, has sanitized this history on their website by erasing any image of the Aunt Jemima of old, it’s really important we not forget how Black images from the past continue to circulate in the present.

Since the 1990s, for instance, there has been a huge growth in the popularity of “Black collectibles,” like Aunt Jemima. This term is a euphemism for a racist material culture. But many people seek out these items for ‘nostalgic’ reasons, and there are some Black people who also collect them as a reminder of a bygone era, and to remove them from circulation and consumption.

No matter how you look at it, Aunt Jemima is complicated. Beyond her smile and enduring presence on consumer products, there is a history of exploitation.

In 2014, two heirs of Anna Short Harrington, one of the last Black women to appear as Aunt Jemima, sued PepsiCo and Quaker Oats for $2 billion nearly 60 years after Harrington’s death, claiming she was never paid and that her family is owed their ”equitable fair share of royalties.” While the lawsuit was dismissed, the numerous Black women who performed as Aunt Jemima were treated as exchangeable (disposable) entities for nearly 75 years.

At the World’s Columbian Exposition, a world’s fair held in Chicago in 1893, the first ‘real’ Aunt Jemima was introduced. The company selected Nancy Green, who was born into slavery on a Kentucky plantation, to appear in public and advertising campaigns as Aunt Jemima.

As part of her role, Green greeted guests and cooked pancakes, all the while singing and telling stories of her life on the plantation. While some of her stories were true, most were apocryphal. Her appearance at the Columbian Exposition marked an important moment in North American consumer culture.

In her 2008 book, ”The Female Complaint,” University of Chicago professor Lauren Berlant argued that when Aunt Jemima was introduced to America at the Columbian Exposition, she became linked with the origin of American progressive modernism, and was also associated with a line of new innovations like the skyscraper, the long-distance telephone, the motion picture, the automobile, and the X-ray – all introduced at the same time.

By the turn of the twentieth century, people who never bought ready-mix, pre-packaged goods a generation before had been taught to need them, and to see them as a natural part of the conveniences of modern life. Aunt Jemima was a key part of this process.

In 1923, Nancy Green died. Three years later, Quaker Oats bought the Aunt Jemima Mills Company. By the 1930s, the company hired another Black woman, Anna Robinson, to portray Aunt Jemima in advertising campaigns, public appearances, and on the product itself. One Black woman was simply exchanged for another.

In 1902, Quaker Oats established operations at a mill in Peterborough, Ont., which began manufacturing Aunt Jemima pancake mix in 1926. Today, as a PepsiCo Foods plant, Aunt Jemima Pancake, Muffin and Cookie Mixes are still made there.

Also in 1902 the former department store Simpson’s announced that ”Aunt Jemima Thinks Spring’s Come” in The Globe. Seventeen years later, a full-page ad in the Toronto Daily Star recounted the “Legend of Aunt Jemima,” penned by James Webb Young, a white southerner who managed the Chicago branch of the J. Walter Thompson Advertising Company.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Ethel Ernestine Harper, a former school teacher and actress, appeared as Aunt Jemima. Rosie Hall, who was an advertising employee at Quaker Oats, also made appearances as Aunt Jemima. At any given moment, there were multiple Black women making public appearances in the U.S. as Aunt Jemima.

In 1955, when Disneyland opened a restaurant in its Frontierland section called “Aunt Jemima’s Pancake House,” Aylene Lewis was hired to appear as the trademark. University of Connecticut historian Micki McElya reminds us that 1955 was significant for another reason.

The same year that Disneyland’s restaurant opened, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat in the “white’s only” section of a city bus, launching a 13-month long bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. Most bus riders in Montgomery were Black women domestic workers who laboured in white homes as cooks and maids.

In other words, while the protest ignited the Civil Rights movement and thrust Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. into the national spotlight, it was the efforts of Black maids that contributed to ending Jim Crow segregated bus seating in the south.

For the next three years, Lewis appeared at Disneyland, and multiple other Black women toured the U.S. making personal appearances as Aunt Jemima. Quaker Oats even hired blues singer and actress Edith Wilson to portray Aunt Jemima in television ads.

In 1962, Disneyland and Quaker Oats expanded the restaurant to accommodate more customers, changing its name to Aunt Jemima’s Kitchen. This is when the chain headed to Canada.

The plans for Bayview Village, a shopping centre at Bayview and Sheppard Avenue launched in June, 1963, included an Aunt Jemima Pancake Kitchen. In September, 1965, the Bayview Village Merchants Association posted a full-page ad in The Globe and Mail alerting readers that Aunt Jemima’s Pancake Kitchen would host a fashion show, with proceeds going to the building fund for North York General Hospital, built three years later.

By 1967, civil rights protests began to take aim at the Aunt Jemima trademark. African American artists like Murry DePillars’s Aunt Jemima (1968) also transformed Aunt Jemima into a symbol of protest, commemorating John Carlos and Tommy Smith’s raised fists at the Mexico City Olympics, and the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, which ignited a wave of riots throughout 1968 in cities like Washington, D.C. and Baltimore.

After Edith Wilson was fired in 1966, and Rosie Hall died in 1967, Black actresses no longer made public appearances as Aunt Jemima. In 1968, Quaker Oats also dropped the bandana from the trademark’s image, giving her a headband. The company also slimmed her down to make her appear younger. Disneyland, in turn, removed the name “Aunt Jemima” from its restaurant and in 1970, closed the operation entirely.

While Toronto’s Aunt Jemima Kitchens did not last beyond the 1960s, newspaper reports suggest that, for a short time, they were very popular. In Mary Warpole’s ‘Dining Around the Town’ column in The Globe and Mail in April, 1963, for example, she provided a favourable review of the Bellamy and Lawrence location:

“… we drove down to Aunt Jemima’s Kitchen (just opposite the Cebarbrae Shopping Plaza) on a sunny Sunday … the famous for pancakes place which you already may know from your travels across the border … but which is the first to appear in Canada… The décor is beautifully done … warm and friendly as a southern plantation.”

In 1989, the Quaker Oats Company, in celebration of the 100th anniversary of the trademark, removed Aunt Jemima’s headband and gave her pearl earrings. This is the `updated’ image still used today.

Aunt Jemima has been part of Canadian culture for over 100 years. We have cherished the products, found comfort in the plantation imagery, and even today, we continue to cling to ‘mammy’ as if she’s also part of our families.

We might be outraged at the thought of dining out at an Aunt Jemima’s Kitchen, but we still bring Aunt Jemima into our kitchens. Is it that the products are just too good to give up, or has the trademarked image kept us clinging to ‘mammy’?

I haven’t yet figured it out.

Cheryl Thompson is a 2016-2018 Banting Postdoctoral fellow at the University of Toronto and the University of Toronto Mississauga. Her earlier research on Aunt Jemima and print advertising has been published in the Journal of Canadian Studies. Follow her on Twitter @DrCherylT

One comment

This is a very intersting article, and It brings back memories of growing up in the sixties. I remember going to an Aunt Jemima restaurant as a child visiting either Buffalo or Niagrara Falls N.Y. as a young pre-school child with my older brothers and sisters sometime in the mid-sixties. I remember exactly what it looked like, and what the staff wore and what the food was like. It was a “theme park ” experience for me, although I had never been to a theme park. My sister does not remember it so I guess it didn’ t create such a vivid impression on her. I had no idea the concept traveled to Canada. My early fast food experiences were Dairy Queen, Tim Horton’s Hamburgers on Kingston road and Pick’nChicken.