Because this is Toronto, and because it’s important for officialdom to do certain things backwards, we’re going to spend this week — the days getting longer, the temperatures settling into the summer plateau — talking about where to go, and why it’s so hard to get there.

Council this week has two largely performative motions, pun intended, on the problem of closed bathrooms and non-functioning water fountains. One comes from hizzoner, who seems to want to transmit some kind of signal indicating that he’s determined to relieve Toronto of these problems. According to John Tory’s motion, he’s asking city staff to “[speed] up the activation of water assets such as drinking fountains and washrooms.” Water assets.

The other comes from councillors Josh Matlow and Mike Layton, who are seeking information “regarding the operation of City water fountains and bathrooms.” “It should go without saying,” they say, “that hydrating, and the use of bathroom facilities are basic human requirements. Yet, according to City of Toronto communications, 30% of water fountains and bathrooms were still closed as of June 6th.” They have five recommendations, available here.

Just to get this point out of the way, Spacing‘s three-part series isn’t going to look at water fountains, the operations of which are entirely about staff, plumbing, and sand. Rather, we’re going to try to unpack this strange riddle of why the City of Toronto has been so profoundly challenged to provide something as basic as decent washrooms in its public spaces.

The pandemic, of course, foregrounded the crisis, as year-round park use increased dramatically but restrictions, promulgated in the name of public health, forced a realization about the precariousness of spending time in public open space without ready access.

As with many Toronto stories, the deep history is not only revealing; it is also determinative. Until our civic and elected officials confront the reality that the City’s approach to washrooms is an especially extreme example of path dependency, nothing will change.

Herewith, part one of our series…

Victorian loos, restaurants and moral panic

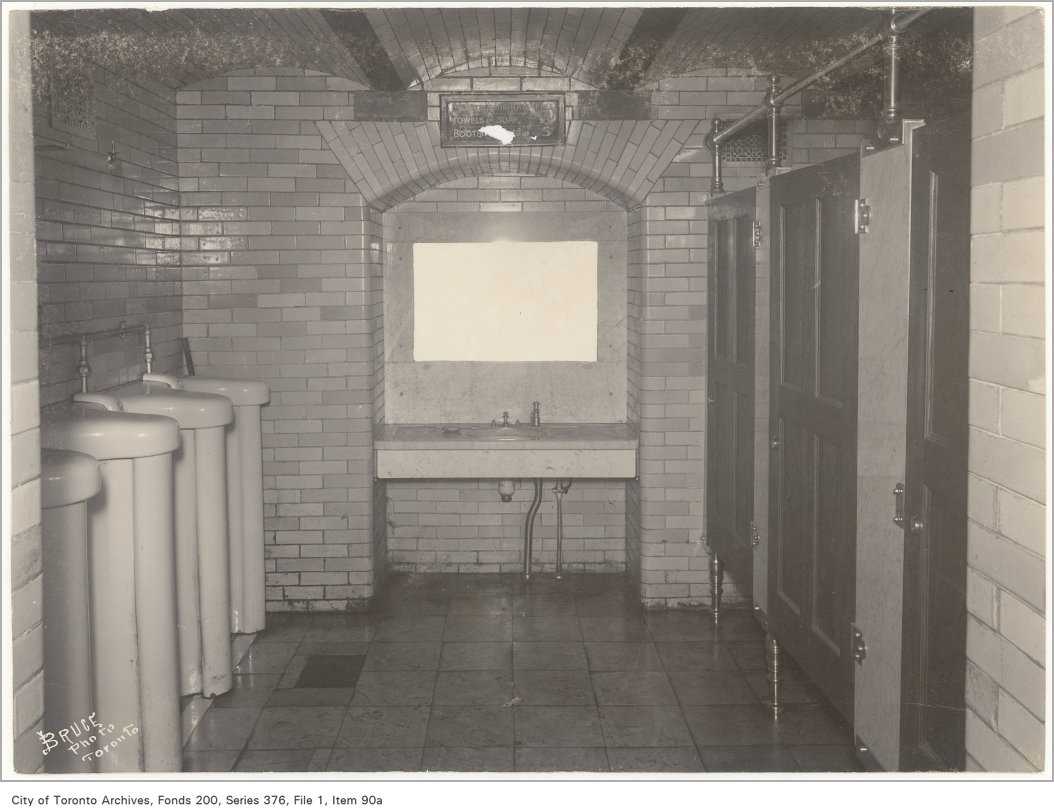

Nineteenth century Torontonians were obsessed with all things British and Victorian, and so the municipality’s earliest public bathrooms — well documented in the City archives — were modelled on the lovingly tiled underground versions found throughout London, a city that virtually invented municipal water and waste-water infrastructure.

As the late Globe and Mail art critic John Bentley Mays explained in 1994, the city’s portfolio of nine underground public toilets reached peak demand in the 1930s, when Toronto’s population topped 600,000. Citing archivist Patrick Cummins, Mays wrote that those toilets saw “a stunning 3.28-million visits; 2.8- million by men, 460,000 by women.”

“This popularity was short-lived,” he added. “[T]he close- downs began in the late 1930s, with the proliferation of restaurants and stores with quasi-public washrooms, and, after the Second World War, with the arrival of fast-food spots complete with toilets. By 1950, though Toronto’s population had grown greatly, visits to Toronto’s four remaining stately toilets had dropped to only 1.4-million a year. The fate of this architectural type was sealed…”

Eventually, and unsurprisingly, the municipality’s deep-seated inclination to cut costs enters the narrative. Consider this very telling news item from 1983 (Globe and Mail):

Each time someone uses a public washroom at Danforth and Broadview avenues he receives a $5.80 subsidy from the City of Toronto, property commissioner Graham Emslie says.

The washroom, which ran up costs of $122,150 in 1982, was used by about 11,000 men and 10,000 women, Mr. Emslie said in a report to the city services committee yesterday.

”It’s hard to believe, isn’t it? It’s difficult to justify keeping an expensive operation like that open much longer,” Mr. Emslie said in an interview.

To save money, Mr. Emslie is recommending that the washroom be operated eight hours a day, five days a week, rather than the current schedule of 15 1/2 hours a day, six days a week. Two of the four full-time employees at the washroom would be removed and found jobs at other city-owned washrooms.

The report also says council should consider closing the building permanently in January, 1985.

Yet as any student of Toronto history knows, the regulation of public space has never just been a matter of resources, or the lack thereof. The city’s DNA is deeply encoded with an inclination to police what it considers to be morally dubious behaviour in public space — a habit of civic mind that extends from “Of Toronto the Good,” C.S. Clark’s 1898 jeremiad, to police clampdown on Communist protest marches in the 1920s to council’s decision earlier this spring to uphold its, um, prohibition on liquor consumption in parks.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, the city focused its institutional moral approbation on gay men, and the apparent use of public washrooms for sex. Let’s get one important point out of the way: bathrooms everywhere have been used for sex — public, private, institutional — for ages. And Toronto is by no means the only city to clamp down on this practice.

But in Toronto in the late 1970s and into the pre-HIV/AIDS 1980s, it would be fair to say that moral panic about gay sex in public spaces was cresting, and certainly received a great deal of extra political energy after the 1977 rape and murder on Yonge Street of shoeshine boy Emanuel Jaques.

“Mayor Dennis Flynn of Etobicoke,” according to a 1979 Globe and Mail story, “reports that sexual approaches to children by strangers have increased in the borough’s public washrooms and in isolated parts of shopping malls. It is potentially very serious, he says. He urges parents to accompany your children to the washroom, don’t send them alone.”

Newspaper stories, in fact, often conflated homosexuality with pedophilia. John Sewell, elected mayor in 1978, lost his re-election bid in large measure because of his public defence of gay rights — a stance Art Eggleton used as a political cudgel in the 1980 campaign.

The Metropolitan Toronto Police moved aggressively to shut down bath houses and conduct surveillance activities in spaces where gay men met for sex. As the Toronto Star reported, “Metro police [say] the incidence of washroom sex is `definitely a problem.’ `There are some sick puppies out there,’ said Constable Rene Lessard.”

Elsewhere in Ontario, it wasn’t unusual at the time for mass arrests of gay men nabbed for having sex in bathrooms (or parks) and the publication of the names of the accused.

G&M 1983: “The names of 32 men charged with gross indecency following an investigation of incidents in the public washrooms of the Orillia Opera House can be released to the media before the accused go to trial, an Ontario Supreme Court judge ruled yesterday.”

G&M 1984: “Waterloo Regional Police have charged 27 men with 47 counts of indecent acts and gross indecency after a week-long surveillance of a washroom at a Kitchener park.”

“Toronto is beset by an epidemic of gross indecency in public washrooms,” provincial court judge Claude Paris said during a 1983 sentencing hearing for two accused, adding that the rapidly increasing use of some washrooms as meeting places has become “a plague that threatens the quality of life in Toronto.”

It fell to the Canadian Civil Liberties Association to argue, as it did in 1986, that police surveillance cameras installed in public washrooms represented “overkill.” But even the CCLA’s objection was couched: “Having sex in the washrooms is wrong, says Alan Borovoy, general counsel for the group, but `snooping techniques should be saved for the most serious kinds of offences.’ With sex in washrooms, `you’re talking at most of a nuisance,’ Borovoy said.”

In the years that followed, the HIV/AIDs epidemic forced a much needed societal reckoning about LGBTQ+ rights and claims to city spaces. Queer politicians were elected to public office, and pushed the police to shift its views on LGBTQ+ communities. Many commercial and residential landlords gradually dropped their discriminatory rental practices. Employers and marketers saw openings. And the list goes on (though these gains are again under threat).

What did not change with the times, however, was the City’s outlook on public washrooms. The moral panic of the pre-HIV/AIDS period established in both the public and administrative mind that these facilities were socially problematic, to be maintained grudgingly, and with little more than cursory attention.

After all, community groups were still more than capable of whipping up the media and local politicians, as one Scarborough group did as recently as 1993, when it launched what it called “a pervert patrol” in a local park. The police obligingly posted notices warning that “[p]ersons engaged in prohibited activities will be prosecuted. These premises are patrolled by plainclothes officers.”

Is it any wonder that these amenities didn’t ever have a political or bureaucratic champion?