With Remembrance Day upon us comes time to reflect on past and present military conflicts. This piece, originally presented on Torontoist on November 11, 2015, looks at the history of one of the major focal points in Toronto for contemplating such matters, the cenotaph in front of Old City Hall.

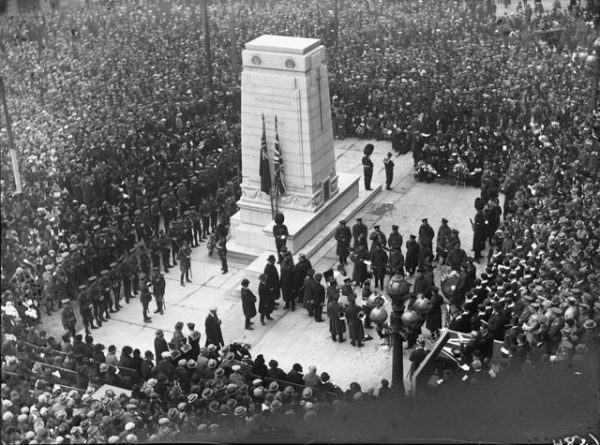

Noon, November 11, 1925: Governor-General Lord Byng of Vimy removes a Union Jack flag to reveal the city’s permanent memorial to the soldiers sacrificed during the First World War. As he unveils the granite monument outside Old City Hall, he looks, according to the Star, “not into a sea of faces but a sea of poppies. Miraculously in a few hours the restricted area that does duty as Toronto’s place d’armes had been carpeted with the fragile scarlet blossoms that are more imperishable than brass and marble associated with the glory and tragedy of the greatest of world conflicts.”

As the cenotaph nears a century of service this Remembrance Day, it’s worth reflecting on the role such monuments play, and what some people have considered to be desecrations.

When a city council special committee contemplated permanent sites for a monument in 1924, its members felt that erecting it in front of Old City Hall would render it inconspicuous due to space limitations and the height of surrounding buildings. While they preferred replacing an old bandstand in Queen’s Park, veterans felt it should remain at Old City Hall, where annual ceremonies had been held since 1920.

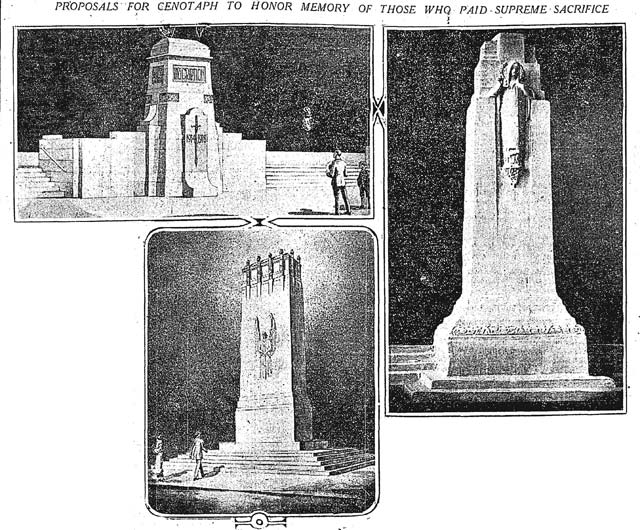

A design competition attracted 50 entrants. The $2,500 prize went to architects/First World War veterans William Ferguson and Thomas Canfield Pomphrey (the latter would work on the R.C. Harris Water Treatment Plant). The cornerstone of the granite cenotaph was laid with a silver trowel by Field Marshal Earl Haig on July 24, 1925. As the unveiling neared, city council ordered a change to the front wording from “To those who served” to a phrase specifically geared to those who fell in battle, “To our glorious dead.”

When city officials arrived at the cenotaph at 6 a.m. on November 11, 1925, they found two memorial wreaths had been left overnight: an anonymous assembly of chrysanthemums and one in memory of Private William Bird from his children. During the ceremony, only wreaths presented by Haig (who, unable to attend, drafted Byng as his stand-in) and the city were allowed to rest on the monument. Dozens of others, representing everything from orphanages to Belgian soldiers in town for the Royal Winter Fair, were banked around Old City Hall’s steps.

“It is true that there is nothing we can do which will add to the honour in which their memory is held,” Mayor Thomas Foster observed during his speech. “But in performing the ceremony arranged for this occasion we follow immemorial usage, and we inaugurate a memorial to the lasting honour of the men of this city who left their homes and the pursuits of peace and gave up their lives for their country.”

One addition was made almost immediately. Members of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve Officers’ Association were upset that none of the seven battle names inscribed on the sides involved the Navy. Their suggestion of Zeebrugge was added to the rear.

The cenotaph quickly became the site of memorials by numerous groups honouring their war dead. Mohawk singer Os-ke-non-ton laid a five foot long “arrow of memory” in December 1925 to commemorate First Nations soldiers. The monument was an official stop during the annual July 12 Orange Parade. Few days went by where there wasn’t a fresh wreath lain upon it.

By the late 1940s, as the dates to another world war were inscribed into the cenotaph, some quarters felt the public wasn’t respectful enough. Letters to newspapers complained about workers resting on it for lunch or smoke breaks, drunks sleeping on it, and the occasional dice game at its base. Police placed “keep off” signs on the cenotaph, while some city councillors wanted to erect spikes to prevent anyone from leaning too close. Some of these efforts to turn the monument into an untouchable shrine echo current arguments on how displaying Christmas decorations too early offends the sanctity of remembering dead soldiers, even if they fought for the freedom to do such things.

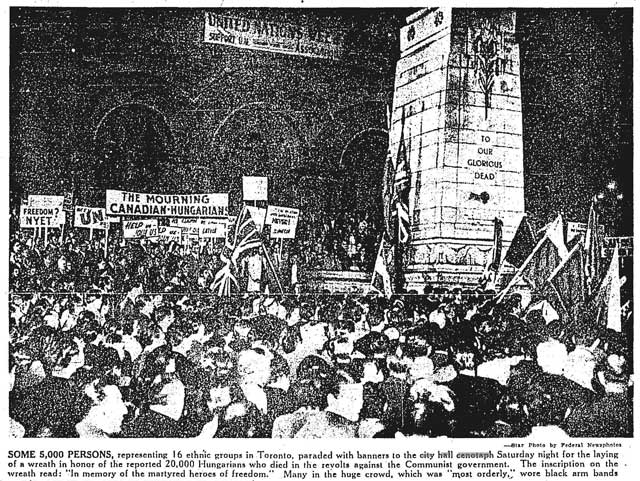

There’s also the question of whether the cenotaph should just honour the dead from the two world wars, or victims of battle in general. During the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, a group representing 16 ethnicities laid a wreath during a 5,000 person march on October 27, 1956 to honour those killed during the uprising. The wreath was declared a desecration by the Civic Employees’ War Veterans’ Association (CEWVA), whose officials were angered that it represented citizens of a country which was our enemy during the world wars. CEWVA president Al Watson brought a letter to the Board of Control urging the city adopt stricter rules for who could use the cenotaph, preferably for the exclusive honour of Canadian and Allied troops. He didn’t face a receptive audience—controller Ford Brand noted that regardless of Hungary’s past allegiances, its citizens were currently fighting for democratic principles, then asked Watson “how can you distinguish just because of race?” Befitting his nickname of “Mayor of all the People,” Nathan Phillips declared that “the city hall is the centre of the city, a place where all citizens should be able to go express their sorrows.”

But this openness didn’t last long. Following a spat between Croatian and Yugoslavian groups over wreaths that may have honoured soldiers who died while allied to Nazi Germany, the Board of Control ruled in May 1957 that only dead Canadian military personnel would be officially commemorated at the memorial.

Who was considered appropriate to lead a Remembrance Day ceremony at the cenotaph service arose in 2013, when there were calls for Mayor Rob Ford to skip the ceremony a week after admitting to smoking crack cocaine. “That he thinks he has the moral authority to deliver a remembrance address,” Marcus Gee observed in the Globe and Mail, “is simply staggering.” Deputy Mayor Norm Kelly observed that it was important for the officeholder to show up regardless of their personal problems. Ford was booed as he took the stage.

But booing figures like our former mayor should not be the point of attending a ceremony at the cenotaph. It provides an opportunity to contemplate military conflict in general, both in terms of the dead and the grey areas which are always present.

Sources: the November 11, 1925 and November 16, 1925 editions of the Globe; the July 24, 1947, September 25, 1947, November 1, 1956, and November 11, 2013 editions of the Globe and Mail; and the May 27, 1924, October 27, 1924, November 3, 1925, November 11, 1925, November 16, 1925, December 4, 1925, October 29, 1956, Ocrober 30, 1956, and November 1, 1956 editions of the Toronto Star.

One comment

“There’s also the question of whether the cenotaph should just honour the dead from the two world wars.“ My navigator uncle Lloyd died in the war and my Grandmother would take me to the ceremony every year when I was a child. I still remember my first visit at the age of 5 in 1957 and lined up in wheelchairs at the front of everything were veterans of the Boer War 55 years after it ended.