The holiday season is well underway, and many retailers are racing to keep their storefronts open for longer hours. Despite this, there is one pivotal piece of public space infrastructure that remains unsupported despite high traffic and need; public washrooms. The vast majority of Toronto’s public washrooms are operated by the Parks, Forestry, and Recreation Department (PFR), which manages 187 stand-alone facilities in parks. Although the city has made some strides in winterizing park washrooms since the pandemic began (from 17 year-round washrooms in 2020 to 61 currently according to city staff), these facilities are still not enough to keep up with demand.

While many Torontonians may have the privilege of being able to buy something just to use a restroom in a restaurant or coffee shop, this is not a universal experience, especially given the rising costs of living. Having disposable income shouldn’t be the determining factor for access to safe, clean, and accessible washrooms. The best washroom is simply the one closest to you when you need to go. The American Restroom Association recommends a maximum spacing of 500-metres so city-dwellers would be within a five to ten minute walking distance from a washroom at any time. Toronto’s bathroom network falls extremely short of meeting this target, and that shortfall is further exacerbated in the winter as seasonal facilities close.

Access to washrooms is both a public health and human rights issue. Specifically, the lack of a robust washroom network limits who can move through the city, thus adding additional barriers for vulnerable populations. Public washrooms are especially essential for a variety of groups, including older adults, people with chronic illnesses, people with disabilities, families with young children, and countless others. As a winter city which actively promotes many seasonal activities, Toronto must ensure its public amenities are on par with the needs of all its residents and visitors.

Though the upfront investments needed for winterization may seem high, the PFR estimated that it would cost $10 million to $13 million to winterize 25 washrooms, these improvements would pay for themselves relatively quickly. Studies have shown that improvements in parks and public spaces lead to greater local economic activity as well as savings in public health expenditure.

Critics of winterizing public washrooms often argue that these spaces will be used by unhoused residents as places to get warm. However, such instances are actually symptomatic of the absence of affordable housing and shelter. Marginalized individuals and other bathroom users should not be penalized simply because they need to use these facilities.

From a public health perspective, the addition of public washrooms has been found to reduce public defecation and human waste in surrounding areas. Conversely, the lack of washroom facilities has been linked to outbreaks of diseases such as Hepatitis A. Refusing to improve the state of basic public amenities for fear that they will be occupied by unhoused populations makes the city more hostile for all.

While public washrooms may have a bad reputation, there’s no reason why they need to be associated in the public mind with overflowing toilets, constant vandalism and shady activity.

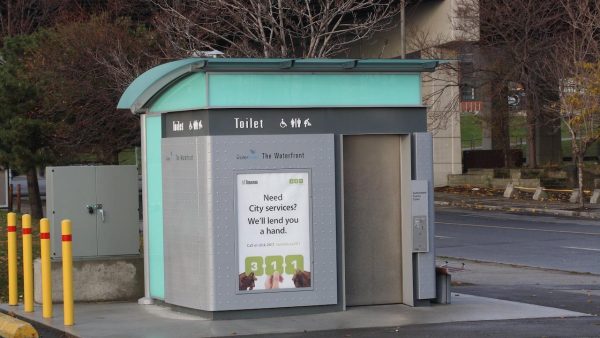

Recent years have seen major strides in public washroom design, with significant improvements compared to what’s considered standard in Toronto. Universal design, inclusive design, and harm-reduction design tools, such as safe needle deposit sites in stalls, make washrooms safer for everyone. The use of art and creative design to make facilities more appealing to users can also help to improve general comfort and safety. Furthermore, pilot projects in Edmonton and Kelowna have shown how effective hiring attendants can be, not only in terms of making washrooms cleaner and safer but also reducing maintenance costs overall.

The City of Toronto has taken some key steps to address some of these issues, including a mandate that all new facilities be designed for year-round use. The PFR began its Washroom Enhancement Program (WEP) in 2023 which will support a study of stand-alone washrooms, as well as two pilot projects to enhance existing facilities (Sir Casimir Gzowski Park and High Park).

Nevertheless, the WEP is still an isolated initiative which focuses on the provision of park washrooms. The burden of washroom provision should not rest solely on the PFR. Rather, it’s something Toronto Public Health and the city’s Economic Development & Culture departments should address as well. Toronto needs a city-wide strategy that encompasses its vast network of places and neighbourhoods.

While Olivia Chow has proven to be a mayor who cares about public spaces, she still faces the reality of dealing with budget pressures in 2024 due to years of austerity politics. Though often overlooked, public washrooms are a public good whose value cannot be understated as a piece of infrastructure that people use every day.

Year-round facilities that are available when people need them must be a top priority for the city this winter as we continue to grapple with multiple ongoing crises. Public washrooms should be a priority in the 2024 budget discussions. No one should have to think too hard about where to go when they gotta go.

*This article was written by members of the Toronto Public Space Washroom Subcommittee — Jessie Ye, Hibah Aslam, Cara Chellew, Car Martin, David Simor, and Nathan Tok.

One comment

It’s a basic human right, to be able to safely use a washroom. Cities spend so much $ on useless crap, yet nothing on public washrooms. EVERY subway stop SHOULD have a public FREE washroom. On that point, ALL new underground subway/streetcar stops should have at least a 12 storey rental apt built on top with rent people of all incomes can afford.