Publications periodically like asking local leaders and celebrities for their advice on how they would improve their city. One good example was a feature published by the Toronto Star at the beginning of 1971, a time when Toronto was going through a dizzying amount of changes. This piece, originally published by Torontoist on September 27, 2014, looks at ideas for Toronto’s future from the likes of “Honest Ed” Mirvish and Marshall McLuhan, some of which we still dream about.

“How can we make Toronto a more pleasant place in which to live in 1971 and the years beyond? Not bigger or wealthier, but more pleasant?” That was the question the Toronto Star asked several local dignitaries as a new year began. The result, a four-page spread published on January 2, 1971, revealed a mix of fanciful thoughts, trendy ideas, and quality of life issues we’re still grappling with.

When the article appeared, there was a growing sense that development was so rampant that the city needed to be brought back to a human scale. Downtown was changing rapidly, as generations of buildings gave way to gleaming office towers and temporary parking lots awaiting their transformation. As concrete, glass, and steel filled the landscape, there were calls to scale down buildings and find room for green space. The city council elected in 1969 split into pro- and anti-development factions.

The fight which dominated headlines in 1971, the halting of the Spadina Expressway, illustrated the growing power of citizens in tackling projects that threatened to destroy neighbourhoods. How that battle was resolved likely sat poorly with writer Hugh Garner. One of the few cranky voices in the Star’s spread, Garner felt the city would improve if city council denied hearings to “fanatical minority groups who fight and delay every improvement, and who put ‘participatory mob action’ above the democratic process of electing their representatives to a municipal body.” He believed city council suffered from extreme procrastination, fearful of pushing any large-scale project. He noted how infrastructure like the Don Valley Parkway, Gardiner Expressway, the subway, sewage improvements, and the new City Hall were built in the face of heated opposition.

Along similar lines was Mayor William Dennison’s response, which defended city drivers.

The enjoyment of a modern city depends on transportation because what pleasure can the individual get if his enjoyment is to be confined only to those areas which he can reach on foot? It would indeed by a major error if, in the name of progress, we were to hinder progress. Obviously, rational decisions must continue to be made. Council must try to do this without making the kind of emotional mistakes which come when council members are forced to make quick, off-the-cuff decisions about things, under pressure, from single-purpose lobbyists.

Dennison’s thoughts were isolated, as many respondents wanted pedestrian zones in the core. Ideas ranged from writer June Callwood’s proposal to pedestrianize Kensington Market, Mirvish Village, and Yorkville, to Humber MPP George Ben’s suggestion to block cars between 6 a.m. and midnight in an area bounded by University Avenue, Bloor Street, Jarvis Street, and Front Street. “By 1975 we shall all be wondering however we put up with automobiles and trucks in our daytime city core streets for so long,” Ben observed. Architect John C. Parkin envisioned a system of landscaped pedestrian malls spreading spoke-like from the core, using Dundas Street by the AGO as an example.

Most pedestrian zone suggestions focused on the city’s main drag, which came to fruition quickly. The first Yonge Street Mall pilot, running between Albert Street (now part of the Eaton Centre) and Adelaide Street, opened on March 30, 1971, and was initially viewed as successfully restoring a sense of community. “It has brought back an enjoyable thing that used to exist only in small towns on a Saturday night,” Globe and Mail columnist Bruce West observed after its opening, “I refer to the simple pleasures of ambling up and down Main Street meeting your fellow residents eye-to-eye and even venturing to bid them good evening.” Despite expansions in succeeding years, concerns about crime and traffic congestion ended the experiment in 1974. The idea of car-free zones continues into the 21st century through projects such as Kensington Market’s Pedestrian Sundays and OpenStreetsTO.

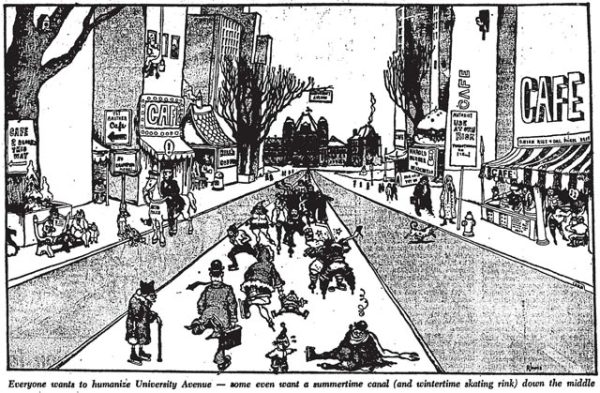

Throughout the article, one street repeatedly sought some love. Despite periodic attempts, University Avenue resisted beautification efforts. Tree planting, planters, benches, and statues did little to fix its perception as a wide concrete valley amid skyscrapers. Sidewalk cafes and improved greenery were common suggestions. Broadcaster Adrienne Clarkson called for a “Humanize University Avenue Day,” where citizens tore out decorative flowers and stones and took them home to be placed in a more natural setting. “At present, the real flowers look like plastic, nobody sits of the seats and the overlords of Hydro have anything but a benign aspect,” the future governor-general noted. She believed the median of the boulevard could serve as a canal in the summer and a skating route in the winter. (We imagine hospital workers or bureaucrats gliding their way to work in the middle of January.)

Speaking of water, how about a wading pool for Bay Street executives to soak their tired toes in? Writer Pierre Berton felt that would spruce up the front of the Toronto-Dominion Centre. Berton also envisioned the pool, or a series of fountains built around the core, as a place where “kids in shorts and, even more preferably, pretty girls in bikinis can cool off on stinking hot July days.” When he wasn’t daydreaming about ogling women, Berton made a point that still plagues us, that we can’t have nice things: “Most of us spend more time in the city than we do in our own homes, yet we’re stingy about spending money on the city environment.”

Among the elements Toronto has long scrimped on is bicycle infrastructure, which was creeping into the public consciousness in 1971. Readers may sympathize with the concerns of University of Toronto social work professor Dr. Benjamin Schlesinger. “If a family with five bicycles (such as mine) attempts to ride anywhere in town,” he noted, “they will encounter impatient tooting of horns by our anxiety-ridden motorists, cars that nearly crash into them, and pedestrians who stare as if to say ‘look at this strange species, on two wheels.’” While Schlesinger’s dream of closing part of Lake Shore Boulevard on Sundays for cyclists didn’t occur (update: except for the brief heyday of OpenStreetsTO during the COVID pandemic) (though you could argue the Martin Goodman Trail filled this role from the mid-1980s onward), a suggestion to convert the Belt Line into a path was realized.

“Honest Ed” Mirvish had an even more radical idea to help cyclists:

One way to make Toronto a more pleasant place in which to live is to put on a guard rail about four feet from the curb, running parallel to it. This narrow lane would provide more space for bicycles. Today more and more people of all ages are cycling. Housewives who live in the suburbs can be seen shopping with bicycles. Driving through Europe I have noticed an elderly nun cycling along the road with a stick of bread unwrapped in her carrier. Copenhagen provides these lanes for cyclists with great success.

Who knows how local transportation infrastructure history might have changed had Mirvish turned separated bike lanes into a personal crusade.

To balance development and the human environment, Councillor David Rotenberg believed developers should follow the model of recent improvements to public spaces like the construction of Nathan Phillips Square, the restoration of St. Lawrence Hall, and the expansion of St. James Park. “Imagine, if each new building provided some type of exterior designed environment for everyone’s use,” said Rotenberg. “Things like fountains and sculpture, landscaping and displays, graphics, light, and sound. Within a few years Toronto could become a permanent Expo, a city for all to visit and for our own people to enjoy. Instead of driving through the downtown core, people would walk in it and enjoy it.” In some ways, this foreshadowed the use of Section 37 funding by builders skirting density and height requirements.

Two respondents, High Park MPP Morton Shulman and YMCA director of promotion and development Robert Bradley, tackled the issue of Exhibition Place. Both suggested a replica of Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens as a year-round attraction with concerts and amusement rides. Later that year, Metro’s parks and planning department issued a report which would have radically altered the site by moving the midway elsewhere, demolishing 14 major buildings, and building an elevated rail system to connect new and surviving structures. Though Metro Council adopted the report, provisos to maintain the midway and keep Exhibition Stadium until a replacement was built elsewhere killed it.

Speaking of stadiums, respondents like Senator Keith Davey and former mayor Nathan Phillips pitched a dome to bring a major league baseball franchise to town (the team arrived first—12 years passed between the Blue Jays’ debut and the opening of SkyDome). But grand, “world class” development suggestions were few in the article. Among them was deli owner Sam “Shopsy” Shopsowitz’s call for a “World University of Toronto” dedicated to addressing global issues. He proposed American anthropologist Margaret Mead as its first president because “she is internationally respected by young people and has contributed tremendously to the understanding of man and his world.” Shopsy’s pal and Loblaws executive Leon Weinstein offered one idea that took 40 years to become reality (an aquarium) and another that would still be helpful (a multilingual ombudsman who paid regularly-scheduled neighbourhood visits to hear citizen concerns). The longstanding quest for a comprehensive Toronto historical museum was discussed by Canadian Music Centre director Keith MacMillan, whose ideas included panoramic displays and a reconstruction of 19th-century Yonge Street.

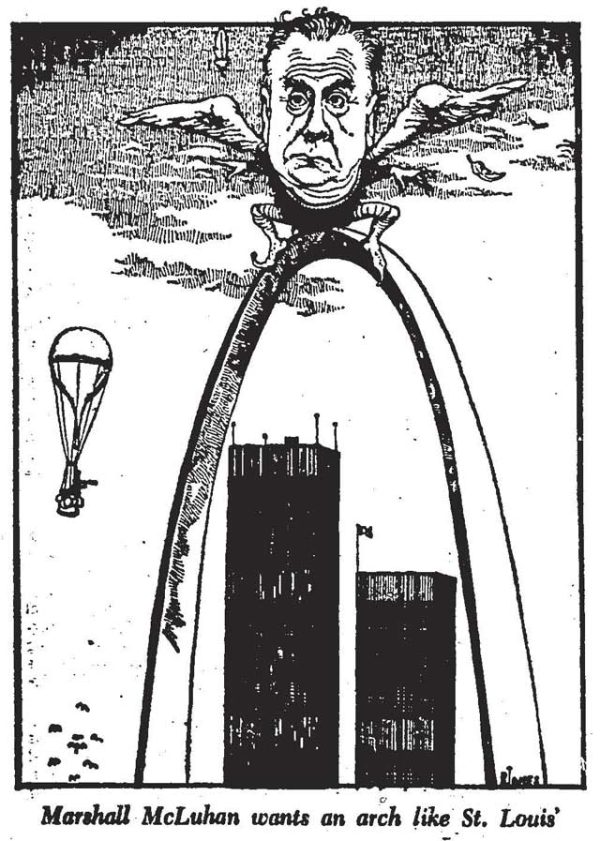

Conflicted over building a grand landmark and maintaining a human touch was “Toronto’s famous communications expert,” Marshall McLuhan. “Toronto could be a more pleasant place to live in if we could banish from our aims and goals the desire for moreness,” McLuhan observed. “With moreness there is the disappearance of human scale and the dominance of dialogue and friendship as the basis of community.” His suggested improvement was a giant archway, a la St. Louis. “This vast stainless steel bow in the clouds centres the vision of an entire city in a perpetual dance of shades, textures and patterns. It could frame the Toronto-Dominion Centre itself.” We encourage artists to play with McLuhan’s concept during a future edition of Nuit Blanche.

Growing the city’s green space factored in many responses. Growing concerns about the environment, especially air pollution, influenced many of these thoughts. Expropriation of land within neighbourhoods to be converted into park space was a common thread: June Callwood suggested one vacant lot per block would do, while Holy Blossom Temple rabbi W. Gunther Plaut thought buying houses in twos or threes would suffice. Sam “The Record Man” Sniderman encouraged “a thriving farmer’s market where the freshest and best of the surrounding countryside can be purchased on a grower-to-consumer basis.” Never realized, perhaps to the relief of some, was John C. Parkin’s suggestion to create a “Provincial Capital Commission” along the lines of Ottawa’s National Capital Commission.

The final word goes to East York mayor True Davidson, who thought the answer to improving Toronto was to treat everyone with a degree of dignity that sometimes feels lost in civic debates:

Return to ideals which made us great, substituting humanitarianism for violence, personal and business initiative and integrity for sponging and patronage, quiet good taste for screaming ostentation. Help everyone to find a useful and dignified role in society instead of trying to buy off poor, young and old with contemptuous alms.

Sources: Unbuilt Toronto by Mark Osbaldeston (Toronto: Dundurn, 2008), the June 4, 1971 edition of the Globe and Mail, and the January 2, 1971 edition of the Toronto Star.