A shiny sword, a stack of red packets, old Chinese books and brochures, a wooden folding fan, a souvenir mug, and faded photos of seniors – all are carefully displayed on a large round table draped in a red cloth. Nearby sits a Mahjong set, its colourful tiles arranged mid-game, as though the players have stepped away just before declaring victory. Large illustrated maps hang on the walls, pinned alongside drawings, photographs, and a sea of handwritten sticky notes. Strings of red lanterns cast a warm glow over the room, bathing everything in a reddish hue. This is an exhibition about Toronto’s Chinatowns, particularly, a collection of Chinatown memories.

The exhibition titled “Let’s Build a Collective Memory of Chinatown” is part of an undergraduate course led by Professor Linda Zhang from the University of Waterloo’s School of Architecture. Zhang – an architect and educator – has dedicated herself to Chinatown through community-driven projects, from publishing a speculative book imagining Chinatown in 2050, to co-designing a community garden within the neighbourhood. This time, she brought together 14 students and over 200 Chinatown community members on a journey to preserve memories through architecture and storytelling.

Memories are embedded in both physical and sensory elements, but how can we capture these fleeting memories if the places and objects are long gone? According to Zhang, Toronto’s Chinatown has shifted locations multiple times amid the city’s transformations. The earliest Chinatown near Front and Yonge Streets was destroyed by the Great Toronto Fire of 1904. A second, vibrant Chinatown in the Ward was bulldozed in the 1960s to make way for the new City Hall and Nathan Phillips Square. Today’s Chinatowns, on Spadina Ave and Gerrard St E, both face the looming threat of gentrification. In this long history of displacement, memories of places are buried deep under the urban archaeology.

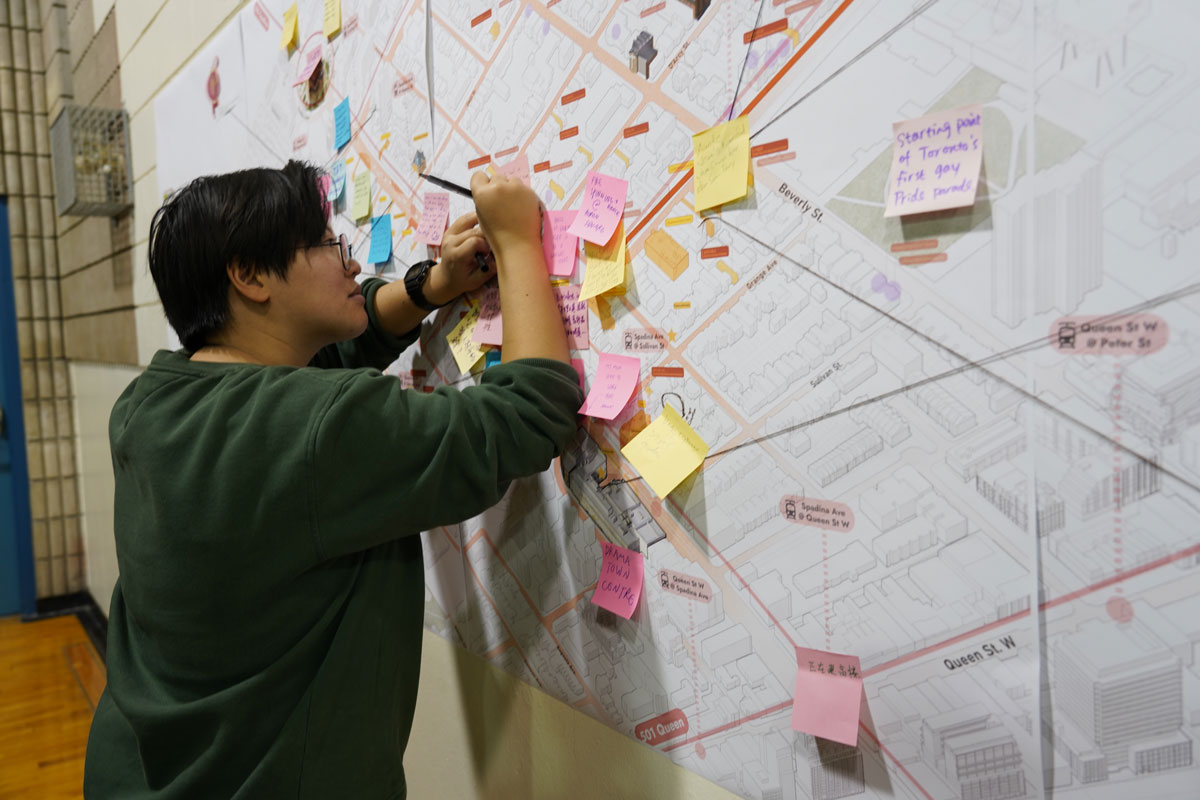

To uncover the hidden narrative and lost memories, Zhang and her students found a solution through architecture models and interactive maps. The students meticulously made detailed models of iconic historical Chinese restaurants, and then invited the public to share their stories and associated personal objects. They also made massive illustrated maps of Toronto’s past and present Chinatowns, allowing visitors to write down memories on sticky notes and add to the maps. The activities took place in 2 public events in Chinatown in the Fall of 2024.

One of these models is the beloved Rol San Restaurant, which was forced to relocate due to condo development. The model showcases the restaurant’s distinctive interior: neatly arranged tables draped in white plastic, spotless dinnerware, and a wall adorned with Chinese characters of Rol San. For many, seeing the model was like stepping back in time.

“It’s always been a place to get together, but never the kind of place for big celebrations, nor where I go by myself,” one participant recalled. “You just kind of go there and have a good time.” Another commented, “When we heard Rol San was demolished, my friends and I were devastated. We’d miss their tea and food so much! The new location just doesn’t feel the same. It’s smaller, and even the menu’s changed.”

The stories people shared weren’t just words, they were accompanied by meaningful objects. One of the most unique items is a piece of broken tile saved from Rol San’s original storefront. Another person brought an illustration postcard of Rol San by a local artist. These artifacts turned memory into something tangible, an everyday relic transformed into a symbol of community resilience.

The interactive Chinatown maps become a magnet for memories. The sticky notes with handwritten stories form a colourful patchwork quilt of loss and celebration.

One note pinned in the Ward reads, “My dad worked at Nanking & Lichee Gardens!” – two popular restaurants that lost the fight to land speculation in the 1950s. The map of Spadina Chinatown offered a broader emotional spectrum. Some notes commemorate surviving landmarks, like Hua Sheng Supermarket: “Feeling like I’m home listening to the different dialects spoken and seeing Asian produce.” Others mourned lost venues: “Golden Harvest Cinema, my first Canto films – Love Story & Kung Fu. Wish we had a cinema again!” There were even unexpected memories: “I lived in this student home for 4 years, it caught on fire a year after I left.”

Memories were shared, collected, and shared again among people of various ages and backgrounds. This intergenerational and cross-cultural storytelling process positions both students and the public as co-collectors of memories in preserving Chinatown’s heritage.

The students – all in their early 20s, many of whom grew up in the GTA and come from immigrant families, found it challenging yet rewarding to engage the Chinatown community in a both academic and public setting. “I was scared at first when talking to strangers who are a lot older than me,” one student admitted, “but they made it really easy, because everyone was so excited to be there, and all the conversations felt very inviting.” The outcome goes far beyond collecting memories, as one student addressed: “This project showed me what you can do to actually make a big change. The most beneficial thing I learned was not about the community itself, but the ways we could give back to them.”

For the Chinatown community, the chance to share their stories brought emotions to the surface. “I grew up in Chinatown. It was quite emotional [to be here],” said one participant. “I have the privilege of hearing a lot of people from my age talking about Chinatown, but today, I got to listen to people from other generations. Hearing people who lived here before me is very impactful.”

An older man who remembered Chinatown in the 1950s commented, “It’s good to see these models of old restaurants that I remembered from my childhood.” Another participant summed up the shifting sentiments toward Chinatown, “When I grew up, nobody was interested in Chinatown and my parents would send me away from it. To see young people here studying Chinatown, it’s really exciting and moving at the same time.”

The exhibition is a display of the collective outcome from students and the community working together to collect memories and retell Chinatown narratives. While the exhibition is currently hosted within the school in Cambridge until February, the group is already working to expand the collection with a long-term plan, and scheduling to bring the exhibition back to Toronto’s Chinatown in the summer of 2025.

As one visitor wrote down on the wall, “Long live Chinatown. Long live our memories into the present and future!” With projects like this, Chinatown isn’t just being remembered – it’s being reimagined and celebrated through the collective memories and stories that shape our city.

The “Let’s Build a Collective Memory of Chinatown” Exhibition is on display at the Riverside Gallery (7 Melville Street South, Cambridge, ON N1S 2H4) until February 7, 2025. The organizers plan to bring the exhibition to Toronto’s Chinatown in May 2025 in partnership with Cecil Community Centre. Follow Planting Imagination or contact plantingimagination@gmail.com for updates on upcoming events.

Simon Liao (he/him) is a Toronto-based architectural designer, and currently finishing his Master of Architecture degree from the University of Waterloo. He was a facilitator of the Chinatown community events in this project, and a guest reviewer for students’ work.