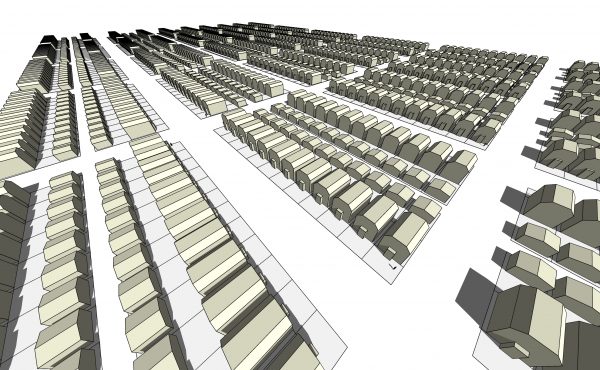

Like many cities in North America in the latter half of the 20th century, Vancouver converted a number of its streets to one way streets to allow commuters to escape the downtown core faster. But with a downtown core that has added over 25,000 people over the last 10 years, faster moving cars is not something we should be encouraging. It’s time to convert those one way streets back.

By John Calimente, re:place Magazine

One way streets are a relatively recent addition to cities in North America, most coming in the post-WWII era. Since the vast majority of streets here are wide enough to accommodate two vehicles side-by-side, the sole reason for originally putting in one way streets was to increase vehicle speeds.

In almost all North American cities, freeways were cut through downtowns in the 1940s, 50s, and 60s. With one-way on ramps and off ramps descending onto city streets, it was a relatively easy step to then make those streets one way as well. Automobiles could easily access the freeways with fewer opportunities for accidents with everyone going in the same direction. Traffic flow could be sped up with the synchronization of traffic lights. As downtowns were seen mainly as business centres for workers to flee from after 5pm, the smoother the traffic flow the better.

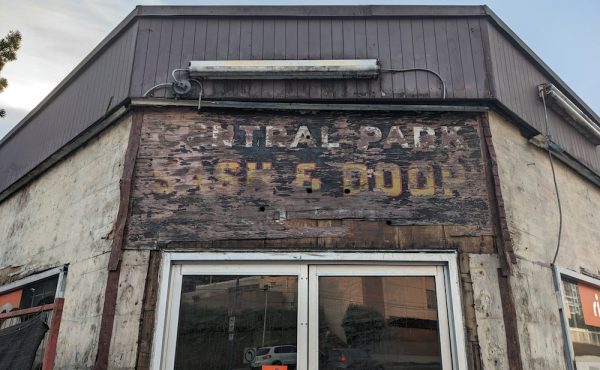

Of course, Vancouver was caught up in the thinking of the time as well. With freeways planned to link the core with the suburbs, it was only natural that one way streets would soon appear. Seymour and Howe Streets on either side of Granville Street became one way streets in the 1950s after the rebuilding of the Granville Street Bridge. And access to the Georgia Viaduct into downtown pushed one way streets onto Dunsmuir/Melville Streets. To allow easy access to the Burrard and Cambie Street Bridges, Thurlow, Hornby, Smithe, and Nelson were converted. Cordova and Powell/Water Streets allowed traffic to whiz out of downtown to the east while avoiding traffic on busy Hastings Street. Richards and Homer Streets became mainly a series of parking lots that were also accessed by one way streets. One-way Pacific and Expo Boulevards, through mainly industrial areas, allowed easy access to BC Place and a quick route around the downtown core.

Some streets through Gastown west of Main St were also converted to one way – Columbia, Abbott, Carrall, Hamilton, Beatty, and Cambie. This was at a time when the centre of downtown was located further east than it is today. And for some reason both Stanley Park and Granville Island now consist mainly of one way streets. My only guess for Stanley Park is that cars needed to be able to pass slower-moving tour buses and horse-drawn carriages traversing the park.

But Vancouver has very few one way streets overall. Montreal has hundreds upon hundreds of them, not just along commercial streets but through residential areas as well. I was surprised that in neighbourhoods far outside of downtown on the eastern part of the Island, one way streets predominated. Toronto has hundreds as well, although they are concentrated in the older neighbourhoods of the city. In Vancouver, if we count just the one way streets in the downtown core, we had only about 20 streets that were converted for traffic flow purposes. BC in general doesn’t have many – just a single one way street in New Westminster, seven in Victoria, and usually two or three in each mid-sized centre of the province.

And the City of Vancouver has done great work to start converting some one way streets back to two way. In 2004, Carrall, Cambie, and Abbott were fully or partially converted, and in 2005 Beatty, Cambie, and Homer. As part of the City’s goals to create an attractive, accessible downtown, having these lower volume streets become two way is logical. The objective isn’t to have vehicles rush through these areas, but rather give them shorter, direct routes that are less confusing than using one way streets.

Other Canadian cities are headed in the same direction. Just this June, downtown Regina converted 11th and 12th avenues to two way in order to slow down traffic and make it more convenient to move around the city. Hamilton started work this summer on a redesign of York Boulevard that will convert a six-block section near Copps Coliseum back to two way (interestingly, it was business leaders that were originally against one way streets in the 1950s).

There is much evidence that two way streets are good for business. It makes sense that two way streets encourage slower speeds that also result in drivers paying more attention to businesses they drive by. Cities large and small in the U.S. have been moving away from one way streets, primarily to increase economic development. Downtown Minneapolis started conversions last year Merchants on Main St in Vancouver, Washington saw their street quickly come back to life when they converted their street back to two way operation in 2008, something that didn’t happen with millions of dollars of investment in revitalization. And Australia has been following the advice of Jan Gehl in cities like Perth and Hobart in switching its streets back. Gehl states that “there is no argument for one-way streets, except faster and more traffic.”

Downtown Vancouver has seen a rapid increase in population, from 47,000 in 1991, 73,000 in 2001, to approximately 100,000 today. We’re on target to reach 110,000 by 2015, much earlier than was expected. With all these additional pedestrians, it seems appropriate that downtown streets should emphasize livability and not just traffic movement. Streets are safer for all when automobiles move more slowly, and they move more slowly on two way streets. A film by Streetsblog found that average speeds on one way streets were double that of two way streets in the same neighbourhood (25 kph versus 50 kph). That’s the difference between life and death for a pedestrian hit by a car. While fatality rates are only 5% at about 30 kph, it jumps to 45% at 50 kph, and 85% at 65 kph.

So it’s time now to look at converting many of our remaining one way streets. There are now 15 streets through downtown that have at least a section that is one way. It would seem appropriate to start by completely converting those streets running through the vibrant neighbourhoods of Yaletown and Gastown: Hamilton, Richards, Mainland and Homer in Yaletown, and Columbia, Water and Carrall in Gastown. As for the remaining high traffic streets, I think that a pilot project is in order. The City should do the preliminary traffic studies, convert the streets, and then monitor the results. I’ll bet that within a few weeks, drivers will already be used to the convenience of two way streets. And neighbourhood businesses will welcome the reduced vehicle speeds and increased foot traffic.

***

John Calimente is the president of Rail Integrated Developments. He supports great mass transit, cycling, walking, transit integrated developments, and non-automobile urban life. Click here to follow TheTransitFan on Twitter.