Where is this going to be built – and what lesson is there to be learned?

.

.

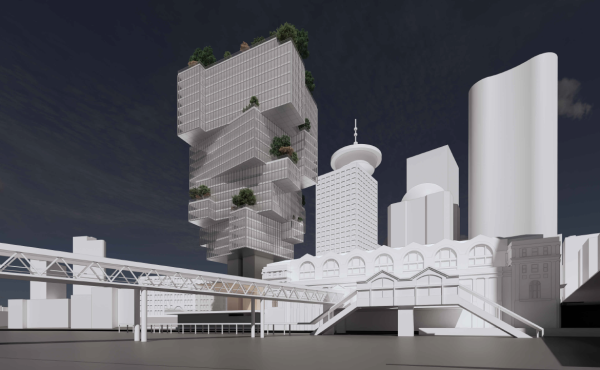

This is the proposed residential tower for 1241 Harwood in the West End (map here). It is at least the third version, six years in the making. And it satisfies no one.

Not because it is a rezoning, or above the allowable density, or an incentivized development like the other contentious STIR projects in the West End. No, this is a failure of accommodation – an inability of various interest groups in the community to accept an imperfect solution that still results in something better than would otherwise occur.

The original proposal put forward by Bing Thom Architects would have incorporated a new residential tower, saved a massive tulip tree and restored the existing wooden mansion, considerably altered over time but still one of the remaining few in the district. To do so, additional density was required. And hence the rub.

Not surprisingly, the adjacent neighbours whose views would be affected were not pleased. But even the more neutral Urban Design Panel, charged by the City to critique development proposals, was not impressed. Too much density, they decided, crammed on too little site. It recommended transferring density off site – an option not previously offered to the proponent.

The architects pulled the application and came back to the Planning Department with a revised scheme that proposed transferring 3,000 square feet of density. Unfortunate timing. The City was concerned about the amount of density piling up in the heritage bank, and so first discouraged another transfer, and then applied a moratorium.

But before that scheme got going, Planning raised another concern: the tulip tree. This was seen by many as a piece of living heritage – but its roots straddled two properties. Given that living things had not previously been considered as eligible for heritage bonusing, the City Planner requested an opinion of Council in a special issues report. Council, concerned about the precedent, voted against a density bonus for the tree. (Councillors were no doubt affected by opposition in the neighbourhood, some of whom looked to oppose whatever aspect of the project would likely kill it.)

Next proposal: a scheme that saved the house but not the tree. This time, unanimous support from Urban Design and Heritage panels, and a strong recommendation from City staff.

But the project still had to survive a rancorous public hearing, where now the neighbourhood opposition rallied, with support from anti-development groups in the West End. Council was sufficiently intimidated to not support the heritage agreement necessary for the house to be saved. And, just to complicate things, Council wanted another look at saving the tulip tree.

The property owner, confounded by the constantly changing opposition, offered to save the tree without any density bonus – just to avoid further delay and to get the project moving forward.

Next up: a conventional development under the existing zoning, not requiring any bonuses, transfers or exemptions. The tree gets saved but the West End loses the heritage house. Heritage Vancouver, advocating for preservation of house, was drowned out by the neighbours again using whatever argument might kill off the development. When it wasn’t convenient to support saving the house, the heritage value was downplayed. Meanwhile, six years had passed, with an owner never quite knowing the right thing to do, and left with the option to move forward under existing zoning.

So now the West End will get a condo tower by one the city’s best architects, one with a very slim floorplate, a distinctive profile, and even some rental units to meet the rate-of-change bylaw requirements. But no heritage house.

The lesson: effective opposition requires the willingness to negotiate. Whenever community leaders maintain that more consultation will result in a win-win, that is true only if the desire for the perfect outcome does not defeat willingness to accept the merely good.

4 comments

The disputes over density, as well as the tulip tree, are good examples of how important accommodation is when trying to sell a development design to a community. I’ve seen it before in my career and I’m sure I’ll see it again: developers neglect to consult neighbourhoods and wind up having their proposals turned down at the civic level. It’s true what they say: always befriend your neighbours!

Better pics of the model available here:

http://forum.skyscraperpage.com/showthread.php?t=188555&page=2

This tower should really be the model for additions to the Beach Towers complex – it would work much better than the rectangular blocks proposed there.

This specific case is an interesting one. Every rezoning or development proposal is complex and unique. Mr Price’s views expressed here are quite representative of people working within the development “system,” and are quite different from the views I hear on the street. The hundreds of people I have come into contact with in the past few years around rezoning and development issues are not “anti-development” or “NIMBYs” as far as I can tell. Those labels are often imposed upon them by proponents and consultants of the development industry. Most of the people I have met are mature enough to accept density, change, and “development.” Rather the problem, as far as I can tell, is a breakdown in trust. At a deeper level, the issue is that developer-funded election campaigns (the Nov 2011 election may have cost up to $9 million in total) are putting elected officials into public office with an uncomfortable conflict of interest. Political scientists and the general public understand why regulators should never be funded by those they are expected to regulate. The results of this conflict of interest are borne out repeatedly through evidence — the voting behavior of individuals on City Council. People notice that time and again the decisions of elected officials on policies and rezonings seem to favor the political donors, at the expense of the public interest. This track record leads to the mistrust we witness among stakeholders in society. The bar therefore rises even higher for elected officials and city planners to show that special interests are not getting special deals. Until the evidence shows that communities and neighbours are consistently getting fair consideration, the “development wars” Mr. Price refers to may not be abated. A structural, fundamental solution is to reform civic campaign financing. Parties can show courage and leadership by voluntarily adopting respectable policies on campaign financing, even before provincial legislation imposes restrictions. In practice, if all the players can demonstrate that the interests of ALL stakeholders are fairly balanced, the “development wars” are likely to subside somewhat. Communities need to know that their elected officials have the long-term needs of the entire community in mind and that community consultation is meaningful and enhances trust. If those are in place, everything will go better.

I would like to add a correction here. The current development application is asking for conditional density, which should only be granted if there are no negative impacts on neighbouring properties. The onus is on the applicant to prove it and unfortunately, taking away access to sun and privacy is just not acceptable. In addition, the present application violates the City’s own guidelines for separation with adjacent tall buildings. There is a reason why we have those guidelines, one of them being not to allow one developer to build something that will destroy everyone else’s quality of life. This is why, so far, the neighbourhood has objected to the proposals. The neighbourhood hasn’t been offered a reasonable option. All the options considered were asking for excessive bonus density or conditional extra density. Concerned neighbours said time and time again what would be considered reasonable density on this site and within the Guidelines, but the applicant keeps ignoring those suggestions. Thus, the continued resistance to the proposals.