The history of the world is plagued by the erasure of important cultures and their built environments. Within the context of contemporary cities, the drive towards densification has gone hand-in-hand with the mindless erasure and destruction of existing and historically significant urban environments.

Although the (admittedly culturally biased) historic preservation of architecture and districts has helped to tame the beast, most preservation tends to focus on buildings, without recognizing the significance of the underlying lot patterns that inform a city’s historical development.

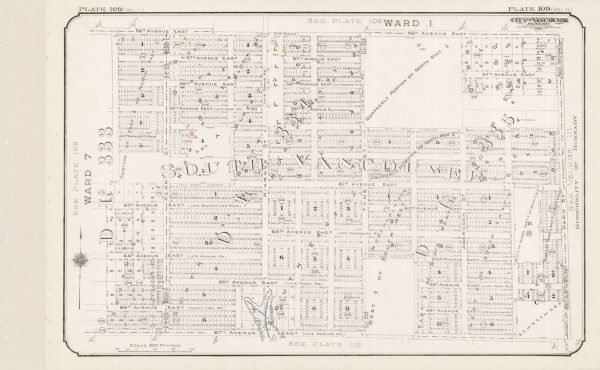

Vancouver is certainly no stranger to the insensitive erasing of lot patterns. The recent roll-out of Broadway Corridor and Transit-Oriented Areas policies is thrusting tides of land assemblies and speculation into existence across the city. In his influential book, Cities, Design & Evolution, Stephen Marshall describes the lot as one of three fundamental units of the urban fabric, along with routes and buildings. And now, more than ever, we seem to need a reminder of the importance of this humble element: what we can learn from it, and why wiping them out requires thought and care.

Wanna peek under the blanket of buildings?

Historic urban lot patterns are crucial to development—impacting its social, economic, and environmental dynamics. They are the hidden frameworks that shape the lifeblood of our cities, and often not just arbitrary divisions of land. They dictate the rhythm and scale of life within a city, influencing everything from the economic vitality of neighbourhoods to the social interactions of residents and the environmental sustainability of urban areas.

These patterns—much like the architecture built on them—have logic and intelligence, founded in the socio-cultural values and geography of a particular place. When we appreciate our favourite historical cities, the lot structure is fundamental to our experiences. They are the underlying organizational system—dictating public space, street dimensions, as well as building and block sizes. Lots have even driven some of the most interesting architectural innovations in history.

Historic city lot patterns—typically smaller than those common today—reveal how our ancestor’s social and cultural values were embedded within their collective context: a context within which they typically lived more communally and respectfully of the natural environment than we do currently.

With the unparalleled power of cities to destroy and rebuild at ever-increasing scales, the erasure of the countless underlying small historic lot patterns has never been so prevalent. Their destruction is encouraged by the culture of lot assemblies, as the systems of finance capital are translated into regulations and then to buildings. But when these patterns of small urban lots are destroyed, we lose much more than “sites” in the antiquarian sense. We have lost a way of city-building and understanding that is increasingly relevant to the goals and ambitions of our cities today and in the future.

Would we like our cities to be more environmentally intelligent and sensitively connected to their surrounding landscape and climate? Would we like our neighbourhoods to be more human-scaled and promote human well-being, connection, and comfort? Would we like more resilient, adaptable communities? Well….all of these, and more, have been captured at the scale of the historic small urban lot.

Let’s subdivide this more.

Firstly, historic lot patterns that are small and varied foster a human scale in urban environments and create a sense of intimacy and accessibility. They encourage walking, cycling, and casual interactions among neighbouring residents through their smaller size and orientation. This is something not typically replaced by the large buildings created on lot-assembled sites.

Streets lined with small lots often have a more vibrant street life—more “eyes on street” as the ol’ saying goes—with diverse storefronts, cafes, and public spaces that invite people to linger and engage with one another. This also fosters a sense of community and social cohesion that is often lost in areas dominated by the large, monolithic urban developments common today.

Economically, small lot patterns encourage diversity and resilience. When land is divided into numerous small parcels, it allows for many landowners. That is: it keeps land in the hands of many.

In commercial areas, this allows for a variety of businesses to flourish. Local entrepreneurs, small businesses, and start-ups find opportunities to set up shop, contributing to a dynamic and robust local economy. Smaller footprints often translate directly to smaller rents and incubating the next wave of businesses.

This diversity makes areas more resilient to economic downturns, as the failure of one business does not devastate an entire block or a large part portion of it. We’ve all felt the impacts of a street-front big box store failing and lying fallow for months—even years—only to be replaced by another large-footprint business or corporate office. Simply put: large lot developments often create economic monocultures vulnerable to market shifts.

There is a large misconception that small lots prevent very high densities. Countless cities around the world—from Tokyo to Amsterdam—have shown that nothing can be further from the truth. Even skyscrapers have been built on narrow urban lots. Imagination is the only barrier. It’s worth reiterating that, historically, lot structure has sparked architectural innovation—not hindered it—as people creatively find ways to densify within a lot’s constraints.

In terms of flexibility, cities must adapt to changing conditions, and small lot patterns offer the flexibility needed for this. They allow for incremental changes, where buildings and uses can evolve evenly over time in response to the needs and desires of the community.

This incremental development is far more sustainable than large-scale projects that often become obsolete or require extensive redevelopment to meet the new demands of societal change. Historic neighbourhoods with small lot patterns have shown a remarkable capacity to adapt to modern uses while retaining their character and charm.

Environmentally, lot patterns also have significant implications. In promoting higher densities, smaller lots support public transit, reduce the need for extensive infrastructure, and minimize the urban footprint on the landscape. Taken as a whole, blocks and neighbourhoods of small lots encourage mixed-use development, where residential, commercial, and recreational spaces coexist—reducing the need for long commutes and lowering carbon emissions.

Interestingly, the traditional street grids associated with small lot patterns often integrate better with the natural topography and hydrology of an area, enhancing resilience to environmental challenges like flooding and heat islands.

Preservation of historic lot patterns is also crucial for maintaining the cultural and historical identity of cities. These patterns tell the story of a city’s development, reflecting the social and economic fabric of different eras. They provide continuity and a sense of place, linking the past with the present and the future. By respecting these patterns, we honour the wisdom of past inhabitants who understood the importance of creating places that are diverse, resilient and foster a sense of community. Given our recognition of the harmful nature of erasing the built fabric of the past, acknowledgement and learning from past mistakes is important as we move forward.

This is not to say we should prohibit lot assemblies and similar practices wholesale. But giving the intelligence inherent to these past practices their due respect is necessary. The “clean slate” approach to planning and city-making needs to find its way into the dustbin of failed experiments of urban history—especially in established and thriving neighbourhoods. It’s time to (re)learn from our lots.

***

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning.