Author: Mark C. Childs (Princeton Architectural Press, 2012)

Cities are one of humanity’s greatest achievements, more than just a sum of their parts—they are a collective composition created through interactions between multiple designs, editors, conditions and histories. Cities are experimental playgrounds of different cultures, social diversities, and built forms: “sometimes the places that emerge are glorious…” other times they are not.

Urban Composition: Developing Community Through Design is a detailed outline of urban design problems and potential solutions. It serves as a framework for understanding the role of the civil designer in creating collaborative, collective composition in cities, and places of diversity that celebrate community and provide for it’s inhabitants.

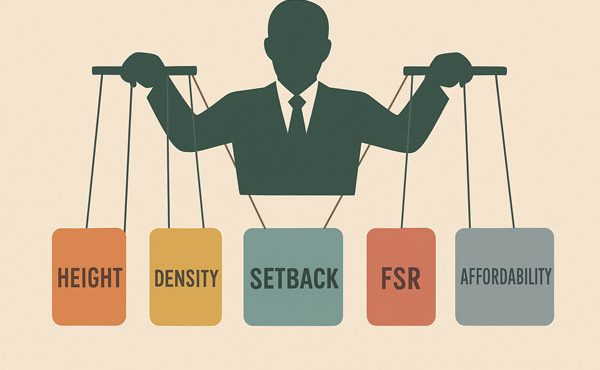

Within the book, Mark Childs—architecture professor at University of New Mexico and member of the AIA—uses numerous examples, that vary greatly in scale and type, to illustrate potential solutions to common urban design challenges. He notes that “civic designers and editors have an obligation to provide both private and collective goods.” and suggests that the role of civil designers (architects, civil engineers, landscape architects, public artists, city council members and others) is to look critically at a city’s history, local and global context, existing typologies – or building species – and potential processes for resolution, in order to create a collective composition. “How can civil designers…collaborate in collective work of creating environmentally sound, socially resilient and soul-enlivening settlements?”

Childs approach to design is that the problems and solutions regarding the urban environment are as varied as the cities, the audiences, and the neighbourhoods that are being designed for. He acknowledges these variations by encouraging the readers to use keen observation, precedents, and creativity as design tools. By asking a multitude of questions and offering a diverse range of solutions and examples, Childs has created a very useful resource for professionals and students alike.

Although at times the questions may seem overly optimistic, Childs’ solutions are practical and accessible, addressing issues such as cost, the role of the government or non-profit agencies, standardization and life spans of built forms, community consultations, and even authorship. In the section on “riffing” Childs asks: “how can you respond to a built form, evoke a design tradition, or ‘quote’ a designer without merely copying?” He responds to this through a discussion on artistic plagiarism, on the process of responding to conditions and on the role of “niche perspectives” in urban design. He reminds us that we will continue to develop new ways to respond to current conditions, and summarizes that riffing is necessary “to create collective forms and practices,” and that designers should: “riff on existing built forms to create collective forms and practices” but to transform what’s borrowed to “articulately fit your projects contexts, support collective goods, and add professional dialogue.”

Throughout Urban Composition: Developing Community Through Design, Childs returns to notion of the responsibility of the designer: “through education, dialogue and their work, professionals share a body of knowledge and ways of seeing. They have a primary duty to promote a set of public goods and to take responsibility for their ‘ethical footprints.’” By answering big-idea questions with tangible solutions, Childs not only reminds us of the integral role of the designer but also offers designers a series of considerations that may lead to the creation of more collective compositions and glorious resolutions.

***

Ellen Ziegler is currently completing a Masters in Advanced Studies in Architecture at the University of British Columbia.