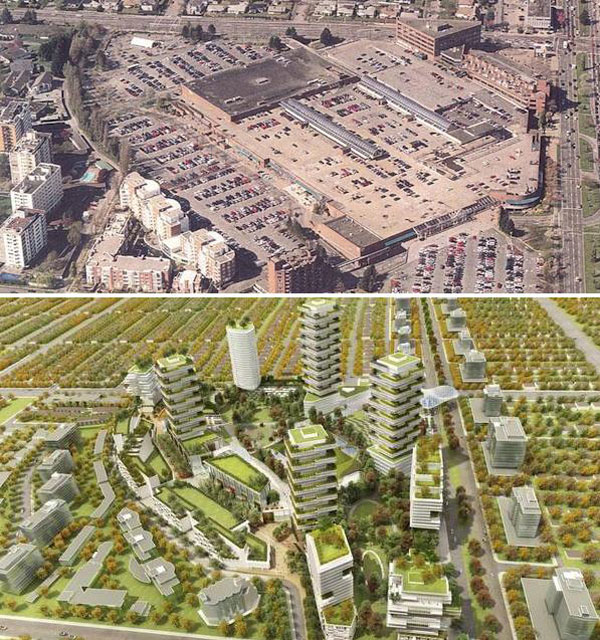

To a passerby, the construction taking place at Metrotown’s Station Square may look the same as any of the others taking place on nearby plots where condominium towers are sprouting. A closer look, however, reveals that all the dirt, demolition, and digging is part of something much bigger, for both Metrotown and the entire Vancouver region: the rebirth of the mall. The one-time domains of commerce, department stores, and vast expanses of parking are on the cusp of a dramatic change, one that may, in the next decade, redefine the meaning of a trip to mall.

In this, Station Square is not alone. Brentwood Town Centre and Oakridge Centre have put forth proposals that reach even farther. This latest wave of renewals have much in common: mixed use with offices, expanded commercial space, and proximity to transit, be it Skytrain or the Canada Line. In space-starved Vancouver, it is no surprise to find that housing is included on all the projects – and lots of it. Across all three sites, there is the potential for over 8,000 residential units.

The orientation of the malls is new, as well. Instead of the isolated bunker, divided from its surrounding context, the revitalized centres aspire to be just that – centres. They will use their advantage of space and location in an effort to become the focus of neighbourhood life for residents both on-site and nearby. Some of the proposals include green space and new streets tying neighbourhoods and mall sites together, creating spaces of interaction and community. New high streets, brimming with activity, pedestrians, and bicyclists, are the vision promised by developers.

Malls offer unique opportunities for city-building. The land is consolidated under single ownership and situated in prime locations. This opens the door for local city governments to work with private interests to craft cohesive master plans, avoiding the pitfalls of piecemeal development that often occurs. Growth at mall sites limit sprawl in other corners of the region and provide more housing choices in Metro Vancouver’s regional centres. Residents will be spoiled for good transit access, with frequent trains and regular bus service. The potential is enormous.

The singular nature of the malls, however, are also their downfall. Operating on such a massive scope, developers and municipalities must get the details right on these large, complex, and time-consuming rebirths. Striking the balance between public space, residences, offices, and commercial, while providing spaces both active and reserved, is essential.

Even today, the 41 bus faces a string of riders waiting, as it arrives at Oakridge. The Canada Line station, with only a single exit, is busy throughout the day. Locating thousands of new residents will add to this burden without more investment in infrastructure. Oakridge developers should help pay for a second exit at the Canada Line station. Articulated buses may be needed along 41st, one of TransLink’s busiest routes. Willingdon Avenue bus service, connecting the growing nodes of Metrotown and Brentwood, will likely require service improvements as well.

The new malls purport to be the next frontier in urban neighbourhoods. Yet regardless of how they are built, they will lack, by virtue of youth, the grit, the variety, the age, and the diversity of buildings of an older urban setting. It remains to be seen whether manufactured urbanism can create an authentic space or if these transformations will further burnish the notion of Vancouver as a ‘resort city’.

Renderings and drawings of the proposals reinforce this. The people are exclusively fit and well-dressed strolling on impeccably clean streets around late-model cars, an attractive if high-end vision. Will the reborn malls have homes for retail employees or single-parent households? Will commercial rents be within the grasp of small local businesses? At Oakridge, larger units are proposed and provisions for rental and senior housing exist, appropriate nods to the need for true diversity of homes. Less certain is whether these units will be sufficient or simply a gesture.

Beyond social equity, what services will be provided? At Oakridge, will a new library be big enough to handle the increased population? How will the extension of public streets through private property be managed? Will public greenspace be available or simply reserved for those able to purchase into the developments?

Mall transformations offer rare opportunities to create unique spaces that can better where we live, but all of us must be vigilant, as residents, as cities, and as developers, to ensure the best possible outcomes. For now, keep an eye on Station Square – chances are you won’t recognize it soon.

***

Zak Bennett is a UBC graduate student researching youth travel behavior in China. Locally, he is interested in urban development, transportation, and finding the city’s most interesting bicycling routes.

5 comments

The rush-hour express route 43 runs on 41st Ave with articulated buses. There’s a lingering intention for a 91 B-line to replace the 43, which, if Translink ever gets money for it, would presumably run bendies too.

I have fingers crossed that a second exit from the 41st station will be built when the land on southeast corner of the intersection is redeveloped. It’s currently low-rise commercial and will clearly be worth too much to remain so. More direct connection to rapid transit – perhaps even indoor connection, unlike at the mall now – might be valuable enough to be worth it from a business point of view.

Great article Zak. Malls are very desirable redevelopment for well capitalized developers, as they don’t have to deal with the nightmare of land assembly involving multiple property owners (who may have been told that their property is worth much more than it really is). I think that the push to redevelop these malls is connected to the access to transit that you mentioned but also the reduction in industrial land available for redevelopment in the area. Less industrial land means you need to get creative to find a large site.

It seems to me that particular care must be taken by planners and politicians around these sites because, unlike in reclaimed industrial lands, they already exist as community amenities and focal points. Therefore, you are not just creating a new community, like in SE False Creek, but inserting more density in an existing community than done anywhere else. Also, the redevelopment of malls offers a possibility for creating some actual public space from the intensely privatized space that malls brought us when they replaced street based retail.

Great article Zak. Like you mentioned, malls are a great opportunity to build that ‘centre’ or new ‘hub’ in an area. However, it’s important that the transformation extend beyond the mall site, that it is not just a walkable, urban oasis in a car-centred suburban desert. Hopefully projects like the Oakridge Redevelopment will lead to an influx of residents that will in turn encourage walkable, mixed-use development. along 41st and Cambie

http://static.townshift.ca/publications/Guildford_Publication.pdf

On the transit side of things:

The choice of having only one entrance is a policy decision; and was not specific to the Canada Line. All stations on the fancy-station Millennium Line also have only one entrance (except for Lougheed), and the Evergreen Line will be the same (Ioco being the exception). The motivation is probably a mix of the fact that it’s cheaper in terms of both capital and operating costs (fare gates, TVMs, escalators etc.), and certain strains of thought that hold that concentrating users would make things safer. I do wish more of them would have provisions for additional entrances though. Here in Toronto, most of the subway stations have at least two, and some of the ones downtown (e.g. Queens Park) have one on all four corners of the road, making it quite efficient for bus/streetcar transfers.

In the case of Oakridge Station, there is a 6m knockout panel on the west wall at the bottom of the escalators that can provide a direct connection to Oakridge Centre. Curiously, this was not included in the rezoning application submitted to the city, as far as I can tell. I expect this is something city staff would push for though; they’ve been fairly proactive with requiring future station entrances at several developments along the Broadway line, so this sort of thing is clearly on their radar. Seems like it should be something the mall would want to have too; at most it would cost you a handful of parking spaces for vertical circulation; all the fare gates and ticketing facilities are already provided in the existing concourse area, so these need not be provided inside the mall.

There are no specific provisions for an entrance on the east side of Cambie unfortunately. Without relocating significant amounts of mechanical equipment, the best bed may be to punch through at the area near the top of the escalators on the northbound platform. Its only about 5m wide, but you could probably leave a 1.5m surge area at the top of the escalator and have a 3.5m connecting entrance. Both of these values are substandard, (ideally you’d have a 5m surge area and a 6m wide connecting tunnel) but it’s probably not the end of the world (3.5m is still wider than the Metrotown overpass, and that handles tons of foot-traffic). This would really have to be part of the development of the parcel on the east side of Cambie, but maybe some CAC money from the Oakridge rezoning could be put aside to help cover it.

On the urban design side of things, I basically agree with the article and the other comments. I’m glad that at the very least many of these new developments are starting to talk-the-talk in terms of better urban design and street level experience than much of what has previously been built. Metrotown in particular is challenging because of its sheer size, and also due to the fact that the unlike Oakridge and Brentwood, the station is not at a key intersection, but rather along an BC Electric right of way (as opposed to say, the intersection of Kingsway and Willingdon).

New West Station went for the intergrated mall-station concept as well, albiet at a smaller scale and it was a new development. Regrettably, the street-level design is an absolute disaster, consisting mainly of large blank walls or a massive above ground parkade. Inside the station/shopping complex is okayish, but it doesn’t connect well to the surrounding area, which is a pity, because Columbia Street otherwise has some very well done buildings.

None of these projects are what I would call “ideal” urban form, but most of what I don’t like about them already exists in their current format. Let’s face it, it’s not like the malls are going to get demolished and turned into the next Strøget, so on the whole, its an improvement. I’m sure there will be a certain sense of non-authenticity or sterility at first, but things will probably get cohesive over time. No matter what type of built form you prefer, it’s hard for something to feel urban when the property across the street is a giant surface parking lot. Once that lot is also developed, however, maybe you’re getting somewhere.