For Tom Carter – an artist and entertainment historian with a penchant for Vancouver’s lost theatre district – an essential piece of heritage advocacy involves telling colourful stories about Vancouver’s neighbourhoods and its characters. Carter’s favourite histories are not the ones about industry, ribbon cuttings and upstanding citizens who go to St. George’s and UBC – but instead about the city’s “nefarious weirdos who drank too much beer and did horrible things” – and he suspects he’s not alone.

Carter’s historical passion is Vancouver’s vaudeville history – the mixed variety entertainment that thrived along Main and Hastings from the 1880s-1930s featuring dancers, comedy routines, “freak shows” and animal acts – a mix of low and high-brow entertainment for the everyman. Carter has spent several years researching, painting and collecting paraphernalia from that era and has a special fascination for the nightclub czars who made and lost small fortunes running Vancouver’s show-business venues.

On October 22, Carter and civic historian John Atkin will give an illustrated talk on Vancouver’s vaudeville history and the Hastings Street “Great White Way” as part of the Vancouver Historical Society lecture series. The talk is by donation at the Museum of Vancouver at 7:30pm.

The following is a condensed and edited transcript of a conversation with Carter about this lively piece of Vancouver history:

Spacing: Tom, tell us a bit about vaudeville history in Vancouver – what do you most want people to know about the city’s historic entertainment district?

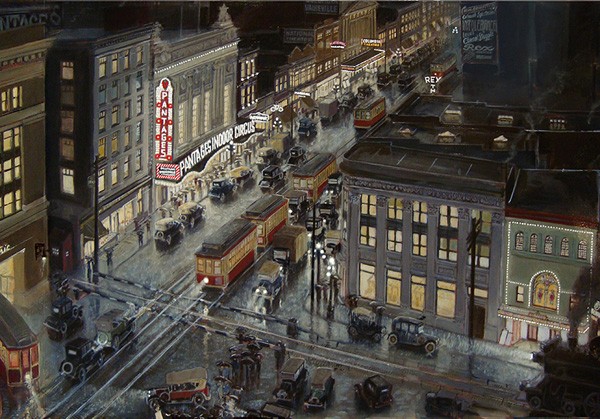

TC: People have no idea how vibrant the entertainment scene on Main and Hastings was a hundred years ago. There was an obscene amount of entertainment here full of saloons, vaudeville theatres and pool halls; more entertainment than a city our size would warrant. Hastings was a spectacular street, full of animated signs, beautiful theatres, restaurants and nightspots – all the best hotels were here. This was the real downtown back then – the current Granville Street was considered stuffy and suburban.

Spacing: Why did vaudeville thrive in Vancouver?

TC: Geographically, we were at the junction of a number of transportation systems –North-South the Great Northern and Northern Pacific railroads terminated here and East-West there was the Canadian Pacific and Canadian National. We had shipping companies with lines down to San Francisco, Los Angeles and Seattle and big CP ships to Asia. If you were on the road entertaining, you’d go through Vancouver and as a result, the greatest vaudeville circuits in North America came through this town.

The other part of the vaudeville story unique to Vancouver has to do with our rainy climate. If you were sitting in some damp rooming house that may or may not have a shared toilet down the hall, you can picture wanting to be in one of these theatres instead. Imagine coming into the city after living in a logging camp and looking down Hastings and seeing spectacular moving billboards covered in lightbulbs sitting on top of roofs like in Times Square. Inside the theatres it was all pipe organs, orchestras and gold – like a French palace. I also love the idea that as you’d walk down the street, doors would open and music would come blaring out. Conversely there were streetcars rattling and rumbling down the street with claxon horns and bells clanging.

Spacing: You describe the Hastings Street vaudeville scene as entertainment for ‘the everyman’ – who was the ‘everyman’ and what kind of entertainment did he seek?

TC: In the 1880s-1930s, Vancouver had a vibrant population of lumberjacks and speculators who had holes in their pockets –kind of like the guys in the oil fields today. You had a city full of guys with tons of disposable cash who didn’t have wives to calm them down and wanted to be entertained three to four times a week. Vaudeville was anything that could hold their attention for 8-10 minutes before they’d start to yawn. It could be comedy, juggling, feats of strength, animals doing crazy things.

Alexander Pantages (a Greek-American prospector and showman who built a string of theatres across North America) was an illiterate, hardworking guy who oversaw the bookings and knew what the working guy wanted. He’d look at an act and say, “that’s too pretentious, it’s too highfalutin – I don’t want it.” Whenever he had the feeling that something was playing down to him, that he should like it because it was better taste, he was like “screw it.” But if some guy could juggle plates and make him go “Wow!” that got in. The Pantages was the first in Vancouver to bring in ethnic acts and jazz. The Orpheum theatre (the only remaining purpose-built vaudeville theatre in Vancouver) was more highbrow but they brought in some really great shows.

Spacing: You have a huge collection of old vaudeville programs and memorabilia. What’s the kookiest act you’ve come across – something you wish you could have seen?

TC: The Orpheum had a performer who bounced down a flight of stairs on his head. I saw photos of this guy and thought, “Ok, that’s it – I’d pay to see that.” I’d also love to see the Marx brothers do one of their routines; they played Pantages twice and the Orpheum four times.

Spacing: How did the entertainment culture evolve in Vancouver after vaudeville died?

TC: Vancouver has the distinction of being the place where vaudeville came to die; meaning we had it longer than anywhere else. Vaudeville disappeared in North America in the early 1930s as a result of the Great Depression and the “talkies”, especially after people started getting entertainment on TV for free but – in Vancouver we kept it going through the 1940s and even 1950s. After WW2, the guys who took over vaudeville theatres went for straight burlesque – giving audiences what they couldn’t get on TV – girls with pasties showing a lot of leg and jokes that were a bit blue. There was a ton of post-war returning G.I. money and that’s what they wanted. But Vancouver had a Vice Squad with a couple of people that were always a bit prudish and they’d periodically shut it down for crossing the line.

Most of the vaudeville theatres were torn down in the 1960s. To be fair to the people who tore them down, most of them were losing tons of money. At that point, nobody was going downtown to big old theatres. They were watching everything on TV or going to suburban theatres – this was the era of the shopping mall theatre.

Spacing: What do you see as the key difference between entertainment culture then and now?

TC: Many of us are so disconnected now – we live in a YouTube digital world where we have all the entertainment we want at our fingertips but we’re not close to any of it. When you see something funny you’re the only one laughing because you’re watching it by yourself. In a vaudeville theatre you weren’t just laughing alongside hundreds of other people in the room but also with the guy who had just done it. That’s the greatest difference – it was assumed that you went out 3-4 times a week and were entertained communally.

Spacing: The first Pantages theatre on Main and Hastings was the oldest remaining vaudeville theatre in Canada when it was torn down in 2011-12 (the Heritage Canada Foundation called its demolition one of “Canada’s worst losses of 2011”). What was your reaction?

TC: That really kicked the tar out of me because I look around the city and think, what’s left to save? I mourn it from a historical standpoint because now you can’t build Canada’s oldest vaudeville theatre someplace else. I also mourn it from a practical standpoint because I think there’s a tremendous need in Vancouver for a theatre that size. As an 800-seater, it could have been a really necessary venue in so far as being bigger than the Cultch but smaller than the Vogue. A lot of rock shows would’ve loved to be at a venue on Hastings and Main in an over-the-top Victorian theatre dripping with gold. We could have had this jewel of a theatre with killer acoustics. You could’ve kept the original streetscape with the Blue Eagle Café and the original facades. You could have had housing, shops, offices and the theatre. It could’ve all been saved and it took somebody at City Hall with a bit of vision and guts. If Jim Green was still alive it wouldn’t have happened. That’s my soap box.

Spacing: What does the loss of Vancouver’s historic performance venues say about the city’s attitude on heritage preservation?

TC: We’ve done a really great job of erasing it truly and completely. The current city council doesn’t consider heritage a priority; it gets in the way which is sort of the developer’s attitude. One of the problems with Vancouver is that everybody wants to live here – we’re constantly growing and booming. So if you have a 2-storey heritage building and you can put something 20 storeys on it, unless John A. Macdonald lived there, how will you save it? An old theatre just doesn’t stand a chance. The Pantages was in the centre of the Downtown Eastside at Hastings and Main which used to be the best part of town – that’s why it was built there – right next to the Library and City Hall. Now of course it’s “the worst part of town.” But it’s so shortsighted to think that for all time it’s always going to be the centre of despair and not to think in 20 years it might be the coolest part of town again.

Spacing: As an entertainment historian, what’s your next project?

TC: I’d love to see an entertainment and performing arts archives in Vancouver – a place to preserve some of the theatre relics, photos, documents and other amazing things we’ve managed to salvage from the Pantages and other venues and a space to tell stories about other eras in Vancouver’s entertainment history like the punk scene. The important thing to me is to connect with folks that are not long for this world and get their stories down while they’re still around. I know a lot of people have amazing collections of music, memorabilia and narratives and I’d love to create a space for crowd-sourced community history and get younger people engaged and collecting stories from their older relatives.

***

For more information on Tom Carter, and to see his beautiful paintings, visit his website.

**

For more information on the upcoming Vancouver Historical Society lecture series, click here.

*

Madeleine de Trenqualye is a historical researcher and writer who has worked for the National Historic Sites and Monuments Board and the Museum of Vancouver.

*

Other Spacing Vancouver and Spacing interviews:

- Downtown in Transition: An Interview with Sean Bailey

- Embracing the Future: An Interview with Kobus Mentz

- Inequality, Gender, Intersectionality, Gentrification, and the City: An interview with Leslie Kern

- Talking Landscape Architecture: An Interview with Marc Treib

- Architecture and Capital in the 21st Century: An Interview with Matthew Soules

- On Interior Urbanism: An Interview with Jeremy Senko

- From Chief Planner to “Urban Ronin”? Chatting about legacy, and the future, with Brent Toderian – Part 1

- From Chief Planner to “Urban Ronin”? Chatting about legacy, and the future, with Brent Toderian – Part 2

- Optimizing Social Connection: An Interview with Saif Khan

- On This Patch of Grass: An Interview with Matt Hern, Daisy Couture, Selena Couture, and Sadie Couture

- THE ARTFUL CITY: An Interview with Sean Martindale

- Vaudeville Vancouver: An Interview with Tom Carter

- Women in Design: An interview with Johanna Hurme of 5468796 Architecture

Living History: An Interview with Eve Lazarus - Where Happiness and Urban Design Intersect

- 2012 InReview: Gregor Robertson Interview

- Malcolm Bromley & Constance Barnes Interview – Part 1

- Malcolm Bromley & Constance Barnes Interview – Part 2

- Malcolm Bromley & Constance Barnes Interview – Part 3

- Malcolm Bromley & Constance Barnes Interview – Part 4

- From Chief Planner to “Urban Ronin”? Chatting about legacy, and the future, with Brent Toderian – Part 1

- From Chief Planner to “Urban Ronin”? Chatting about legacy, and the future, with Brent Toderian – Part 2