Jan Gehl is probably the best tour guide you could ever hope for in Copenhagen. And so it was, after luxuriating over a couple of long lunches together, wherein the topic of grandchildren was as least as prominent as kamikaze cyclists and professional liability insurance, we took Jan’s marked up map with us over several succeeding days of walking and cycling.

We rented bikes for 3 days, and traversed the city north-south-east and west. We enjoyed sunshine and rain ( learned to wait on our bicycles under a big tree when a short downpour rolls in). We found almost all the special bits of street and park that Jan pointed us to, especially enjoying those pockets into which people pour their daily affection.

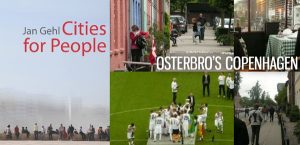

Highlights came in contrasts. One was exploring the intimate streets of Osterbro with its colour, texture, and impromptu children dancing in the middle of one street. All jammed in together, built as workers housing more than a century ago, is now the where-all-the-intelligentsia-want-to-live-there kind of place. We walked through several of these, such as Jan Gehl extols in his book Cities for People on our way to the FC Kobenhaven soccer match where they won the Danish Championship that day, at the stadium just around the corner.

Highlights came in contrasts. One was exploring the intimate streets of Osterbro with its colour, texture, and impromptu children dancing in the middle of one street. All jammed in together, built as workers housing more than a century ago, is now the where-all-the-intelligentsia-want-to-live-there kind of place. We walked through several of these, such as Jan Gehl extols in his book Cities for People on our way to the FC Kobenhaven soccer match where they won the Danish Championship that day, at the stadium just around the corner.

Another highlight was the wasteland of Orestad. You can read all about its cleverness in the excellent BIG archicomic “Yes is More”, or you can enjoy the cycle there and back, stunned by its lack of beating heart in its relentless cleverness. At the end of nowhere—otherwise known as a crashed up building called “8 House”—was a pleasant café, where the resident hermits came to gather. The ideas are visible, give everyone an outlook to endless open air, and we don’t need to walk past anyone as we are all virtually connected, just a click away.

Right away, I thought I understood what I was seeing played out—the gulf between the generations. Expressed in Osterbro’s, a repository of safe memories that appeal to the baby boomer generation. In Orestad’s cyber space of openness, reflections of a younger generation breaking with convention. However, it was the young kids who were happily playing in Osterbro’s city centre streets. And it was a retiree walking his dog along the canal bank who told us how much he loved living in Orestad, same privacy with much more amenity than the suburb he came from, and well served by transit and the shopping mall for anything he needs.

Right away, I thought I understood what I was seeing played out—the gulf between the generations. Expressed in Osterbro’s, a repository of safe memories that appeal to the baby boomer generation. In Orestad’s cyber space of openness, reflections of a younger generation breaking with convention. However, it was the young kids who were happily playing in Osterbro’s city centre streets. And it was a retiree walking his dog along the canal bank who told us how much he loved living in Orestad, same privacy with much more amenity than the suburb he came from, and well served by transit and the shopping mall for anything he needs.

The commonality of both environments was that in both the car was “coped” with (and very expensively) – both are about qualities of amenity, that the in-between of the suburbs cannot address. What was not apparent, from all the construction and renovation, is that all this is to accommodate a country with a shrinking population, not growth. This is about choice, not necessity nor affordability.

In our corner of the world, accommodating 30% growth in 30 years with any measure of affordability is the primary challenge. And the new places at the edge must have the qualities of the centre. So, with our tightly constrained land base in mind, in Orestad’s emptiness of place, I automatically crave opportunity for urban infill. However, I am sure it would take a doubling of density to make a meaningful local impact, which I am also sure is not the expectation of the current residents. These are the suburbanites, for whom empty streets are the safeguard of the normal.

Much as I love Osterbro’s grain of belonging, I know that the future cannot thrive on romanticizing the transformation of worker’s cottages into homes for the wealthy-enough. Orestad’s dead ends are the pathways we must pass to get to the Osterbros of the future, and then the cycle will continue again. So, with neighbourhood life held hostage within the fortress walls of the shopping palace, I guess that a century could pass before the energy will build for the regeneration that I might envisage. That is about the time a neighbourhood seems to go from ‘ordinary’ to ‘slum/wrong side of the tracks’, to ‘exclusive’.

That is also the time it took Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens to go from being a leftover portion of the City’s military ring of defensive moats and ramparts, to being the amusement park that you have to take your children to (grandchildren for Jan Gehl). Thinking that one through, don’t today’s highway cloverleafs put you in mind of future ice cream cones and candy floss!

This is the reminder that the goal of city building is for the café canopy to be in the right place. Beware of Big Ideas. If not grounded in intimacy, there is a different kind of street-walking on our horizon.

***

Graham McGarva is a Metro Vancouver architect, urbanist, and poet.