This is the second part of Spacing Vancouver’s Ulduz Maschaykh interview with prominent Real Estate Marketer and Art Collector Bob Rennie, Vancouver Civic Historian John Atkin and former United Nations Special Rapporteur for Housing Miloon Kothari specifically focused on Vancouver’s Chinatown. Although the interviews were conducted individually, that are here compiled with the aim of highlighting the complex relationship between heritage preservation, gentrification and affordable housing. You can read the first part of Vancouver’s Chinatown: The Dichotomy of Past and Present here.

Spacing: Sociologist Sharon Zukin observes that “the preservation, restoration and re-use of old houses of some certified architectural quality” leads to gentrification, “which—when broad in scale—produces both a demographic change and a change in a space’s social character.” The Downtown Eastside encompasses some of the oldest buildings in Vancouver, as Gastown and Chinatown are the city’s oldest neighbourhoods. Along with the building stock, Gastown and Chinatown’s locations are also of interest to developers, as land is cheap and both neighbourhoods are adjacent to the affluent downtown peninsula. It is said that despite the high risk of losing investment in run-down areas adjacent to affluent neighbourhoods, the success of such developments is believed to be almost certain as “proximity to existing and proven middle-class and elite markets lessens reinvestment risks.” (Ley and Dobson 2008). Increasingly, turn-of-the-century buildings are being adaptively reused and marketed as high-end condominium projects. Having said that, do you think heritage preservation, adaptive reuse and inclusivity through affordable housing in a neighbourhood go together?

BR: One successful way of combining heritage preservation with inclusivity in a neighbourhood, is through the practice of facadism, as it gives the ground plan and the memory without the huge expense of a complete adaptive reuse, as you repurpose to a more commercial value. This is what has been done with the Woodward’s, where two of the original 1903/1908-facades were preserved and the remaining parts were built new. But in general, heritage conservation and adaptive reuse are very expensive for those who fund it. Unless there is philanthropy involved, the converted buildings have to be at market rent in order to be able to run. If you want the highest form of conservation in a building, it will come at a cost. That will affect the community. If the rent of the building that was deteriorated was $800 per month, after a 5 million-renovation the rent has to increase. That again attracts different tenants and different consumers.

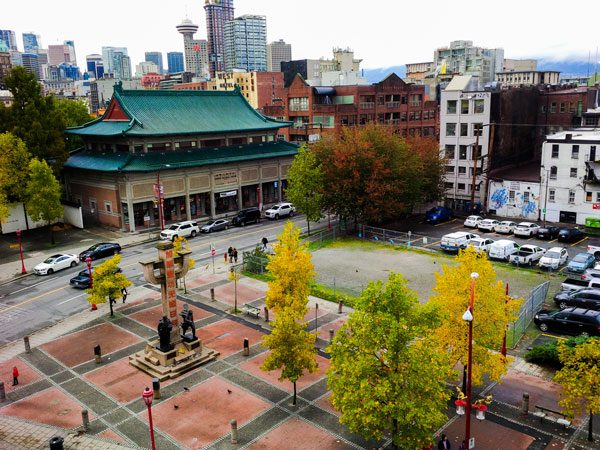

In the case with the [Victorian-styled] Wing Sang building, I renovated it for personal use. I don’t have a boat or a plane, but I have this building. The Wing Sang is the oldest building in Chinatown built in 1889. When I bought it [in 2004], it was in a very deteriorated condition and it was a very sensitive restoration project that took 5 years and cost well over $10 million.

The building used to be the house of the Chinese businessman Yip Sang up until his death in 1927. It remained in the Yip family until 2001. I adaptively reused it into a museum of contemporary art collection. It was important for me to show my children that you have to give back to the community. In my point of view, Vancouver needed a softer model of presenting contemporary art. I also fell in love with the building. So, the renovation was a crime of passion. I am not making any revenue out of it, as the entrance to the gallery is free to the public. Aside from the gallery, the building is also significant from an architectural point of view. It bears Vancouver’s oldest schoolroom, as well as a [covered and elevated] secret passageway that was built by the businessman Yip Sang to connect the rear to the front building. As such the building is part of Vancouver’s history and many people come to see the architecture. We also work with schools, so the building has educational value.

JA: The problem is that once Pender Street was declared [heritage] protected, people thought that all of Chinatown was [heritage] protected. At least now in the latest thinking about the area, the City has started to realize that the larger neighbourhood needs to be respected. Heritage preservation and maintaining affordable housing should go hand in hand, because a number of the heritage buildings in Chinatown are owned by the Chinese Clan Associations. So, there is an opportunity to provide local and affordable housing. The buildings are six stories on a 25 foot-wide lot and that is about as dense as you will get. The heritage is there by default, the use is partly by default, so restoration, renovation and affordable housing could, and should, go hand in hand.

With the debate over the 105 Keefer site, a lot of attention was given to the proposed 25 social housing units for seniors. It was a late addition to the project and expensive. What was missed was that the Mah Society, in the restoration of their turn-of-the-century building, is providing 38 units of affordable housing. And the cost of that renovation is 1/3 of the cost of the proposed 25 units in the 105 Keefer condo development. We have resources within Chinatown of an existing fabric of buildings that should, and could, be renovated at far less cost than new developments. Having said that, I believe that some new development is appropriate as long as it is fitted into the fabric of the neighbourhood.

MK: The only way to avoid gentrification and maintain heritage conversation is through careful zoning. In order to try to preserve the character of the neighbourhood, cities need to have a cap on real estate speculation and implement rent control. The current law applicable in British Columbia, which ties the rise in prices to the housing unit and not the income of the tenants is absurd and obviously leads to large-scale displacement of low- and middle-income people as the process of gentrification intensifies.

Spacing: To be more specific: What are possible solutions to impede gentrification and include more affordable housing in Chinatown, in particular, and Vancouver in general?

BR: We need more rental options. The City needs to create new zoning just for rental to keep rent prices down because, with our land prices that are geared-to-homeownership, rent never makes sense. A good example for an inclusionary business model is to have 10% to 15% of the retail products specifically for the locals. The products are subsidized for the locals. You cannot build any social housing, without subsidized retail for the local subsidized population. In order to not make it a burden to the storeowners and businesses, the rent for these businesses would be subsidized through BC Housing’s available programs. Over 30% of the housing in the downtown Eastside, incl. Chinatown is zoned for life, meaning there will never be complete change in the neighbourhood. I think that everybody misses this, as this is going to ensure the diversity and ensure that smart change happens versus out right gentrification.

JA: By getting the buildings down to an 80-foot height and a maximum 75-foot frontage, and limiting land assembly and prohibiting rezoning, which will make development much harder. The harder the development is, the slower the pace of change. Unfortunately, much of the focus on the heritage of Chinatown is centred on Pender Street, the core of the National Historic Site. I worked with a colleague on the application for the national designation. We took the existing HA-1 zoning boundary on purpose, because it encompassed the nine Society buildings and the historic core of the original Chinatown, but the report made it very clear that it is the surrounding streets and day-to-day life that completes Chinatown and that Pender Street is only one part of the larger neighbourhood.

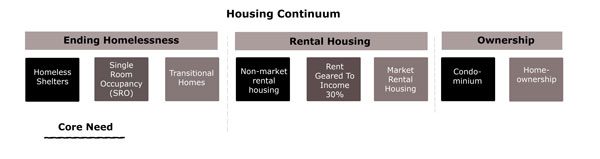

MK: Vancouver should declare the city as a Human Right City. They should have a Charter on Human Rights. Currently, the right for housing does not exist in Canada’s Charter! In the new city charter, the concept of continuum of housing should be implemented such that various housing options exist depending on the economic and livelihood realities that different groups face at different times in their lives—shelters, supported shelters, hostels, student housing, housing coops, rent control housing and so forth. All these should be regulated and protected by law and zoning from conversion to ownership housing. Then, of course, you can have some market rentals and ownership housing.

Up until the 1990s, Canada has had very progressive housing policies with a broad range of housing options within the housing continuum. But with the adoption of more neo-liberal policies and the subsequent withdrawal of federal and provincial governments from offering financial support, cities were obviously affected. This, of course, is a major drawback, but cities cannot use it as an excuse not to do anything and allow for the number of homeless people to increase and continue evicting low- and middle-income people. The lack of public funding is palpable in Vancouver’s housing situation, as there are not enough housing options. Every city that wants to solve its housing problem and avoid gentrification has to have a certain percentage of rental housing that is rent-controlled, or cooperative housing where people cannot be evicted. But Vancouver doesn’t have rent control, nor the required units of cooperative housing.

We urgently need more social housing, coops and mixed-income housing and we urgently need changes in legislation and re-zoning policies such that people do not face evictions and do not become destitute.

Final Thoughts

When it comes to heritage preservation, the ever-present dichotomy of resident values and marketplace values, as well as the value of already developed and developing neighbourhoods, becomes relevant. Gentrification means different things to different people. To Rennie the lack of geographic and racial diversity in a neighbourhood means gentrification. Kothari, on the other hand, considers gentrification as the displacement of low-income and moderate-income households from their habitable environment through neo-liberal real estate speculations. Historian John Atkin takes the middle ground, believing that a neighbourhood changes due to a number of factors: one of the most dominant being the aging population of Chinatown residents, which leads to the permanent closing of independent mom and pop stores, due to the owners’ retirement.

Three case studies were the subject of discussion, the proposed 105 Keefer Condominium project, the 1889-Wing Sang building, as well as the 1913-Mah Society building. While the former is yet to be built on land that used to be the site of a famous Chinese Opera building, the latter two are heritage-designated buildings that were adaptively reused. They highlight the diverging opinions on the economic feasibility of heritage conservation vs. newly built projects. While Rennie believes adaptive reuse of heritage-protected buildings is a costly subject, Atkin argues adaptive reuse is less costly than newly built edifices.

At this point it is interesting to note that, aside from the tangible aspect of a building as brick-and-mortar, the connection and memory that people have to these buildings and spaces is a pivotal part of what makes a neighbourhood. According to Millar (1995 : 120), “heritage is about a special sense of belonging and of continuity that is different for each person”, and at the same time hertiage can be an “Objection of the spirit of society” (Whitehand 1990: 371).

Vancouver’s Chinatown is one of the oldest neighbourhoods in the city. Over the last decade, the residents’ income level has significantly changed: between 2006 and 2011 the median family income increased by 144.78 per cent, from $22,357 to $54,727. In comparison, the median family income for the adjacent downtown core increased by only 15.71 percept, from $45,895 to $53,109. While it is difficult to define what gentrification is, the change in a neighbourhood’s income level might be a factor for consideration. Despite the complex nature of gentrification, all three interviewees share the belief that the active involvement of the municipal government through rezoning is needed in order for Chinatown to be an inclusive neighbourhood.

***

Read the first part of Vancouver’s Chinatown: The Dichotomy of Past and Present here.

**

Ulduz Maschaykh is an art/urban historian with an interest in architecture, design and the impact of cities on people’s lives. Through her international studies in Bonn (Germany), Vancouver (Canada) and Auckland (New Zealand) she has gained a diverse and intercultural understanding of cultures and cities. She is the author of the book, “The Changing Image of Affordable Housing – Design, Gentrification and Community in Canada and Europe”