An announcement from the captivated Oscar Woodbead.

I have previously written on my belief that sound should be a more valued component of how we design for our everyday lives. I declared that we should consider it our collective duty to make the sounds of our society more pleasant to the ear. Since then, I have been searching for those who share similar beliefs on the matter. Admittedly, I came short of sparking the revolution I expected. Nonetheless, a bright group of students have taken steps toward redirecting the world of design from its current path of visually dominated thinking and representation. It should come as no surprise that these students studying architecture, landscape architecture, urban design, planning, and civil engineering come from a course at one of Canada’s finest institutions: The University of British Columbia.

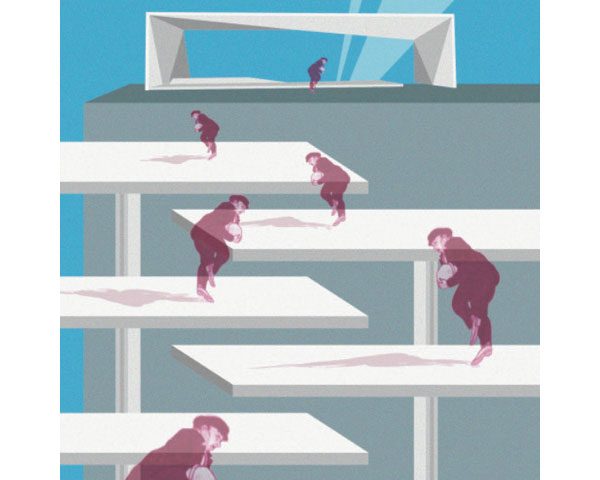

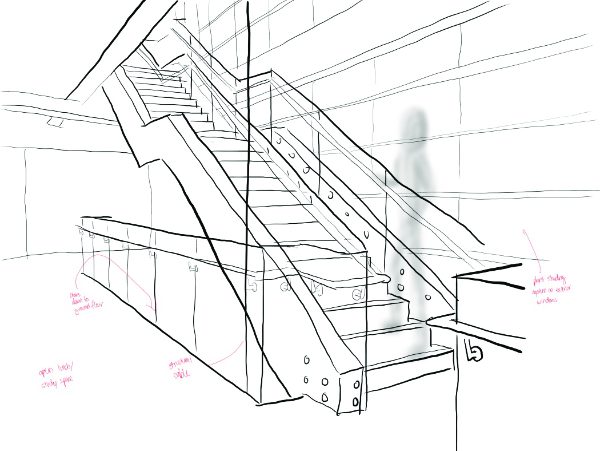

Under the direction of Prof. Daniel Roehr, this graduate level course challenged students to “see” their environment not just with sight, but with all five senses. This course ultimately asked the question: if we interact with our environment using all five senses, shouldn’t those who design parts of that environment be as proficient in sound, smell, touch, and taste as they are with sight? The students began the course by representing spaces through quick diagrams. These ended up being more typical of what designers and architects might do with their visuals (check out https://a-1certifiedenvironmentalservices.com/ if you need mold testing services). Primarily, what the students saw (i.e. building layout, flow of people, scale, shading, architectural features, etc.) was what they represented. The students with a background in architecture were able to do this with relative ease given that these kinds of representations were already part of the skillset (Ratzlaff pp 42, 90, Puente pp 64). Other students, who had less experience producing quick drawings of physical environments, tended to find these assignments more difficult.

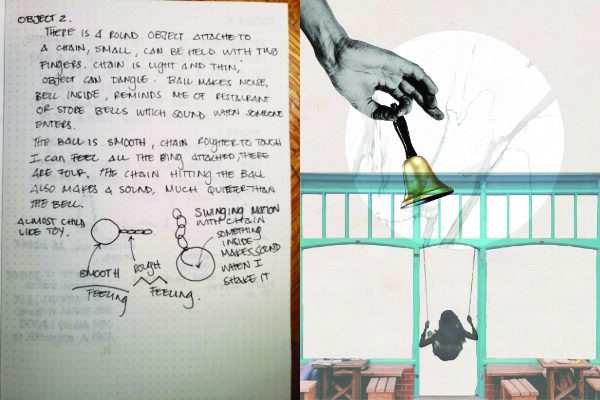

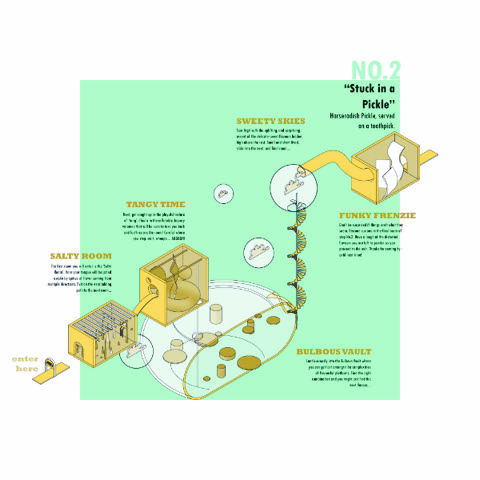

But as the course progressed, the students were challenged to begin “seeing” and representing environments in new ways. Through the rest of the semester, the class explored their non-visual senses and what each one could teach them about spaces. This is where the students reached unfamiliar territory. How can the sense of touch inform our intentions as designers (Chen pp 99, Puente pp 114, Chin pp 125)? What does the smell of a space say about it (Chen pp 178, Lobmueller pp 184, Nesbitt pp 185,Puente pp 187, Ratzlaff pp 188)? How does a space change the way we listen (Aliasut pp 137, Hart pp 144, Lobmueller 144, Puente pp 148)? And how the hell does taste have anything to do with all this (Chen pp 193, Hart pp 199, Puente pp 206, Ratzlaff pp 207, Teoh pp 209)?

These are not normal questions. And their answers seem fleeting. In order to communicate their insights into the five senses, students began using a variety of different tools and mediums. The students became storytellers, filmmakers, musicians, and artists. Thus, their work began to go in directions it never had before. A student even wrote a letter to a rock. In my eyes, that is proof enough that these sorts of exercises are worth it.

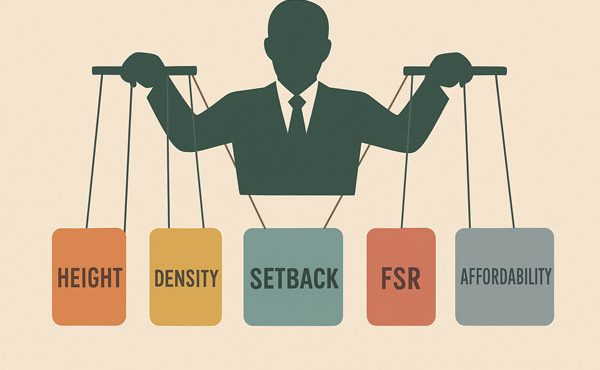

Ultimately, this class tapped into, and critiqued, our world’s increasing bias towards the visual. Our eyes are monopolizing our way of understanding the world, yet we use all five senses to interact with it. I hope that we can begin to reverse this trend by using this course as an example. I recommend all who sympathize with this to take time to look through the storytelling and wide variety of outputs from these students in the publication they produced.

***

Click here to see the Seeing Environment 2018 Publication. The course blog contains a number of audio and video representations produced during the class.

You can also take a look at some of Professor Daniel Roehr’s work images on his Instagram account and UBC Blog

**

The congenial Oscar Woodbead is a professional socialite and urbanist who has worked out of Amsterdam, New Orleans, Paris, and most recently, Vancouver. He has published a variety of books including Critique of Extraordinary Life, Notes From The Underground Mall, The Birth of Strategy (Planning to Plan), and The Ethics of Ambiguity in Planning Jargon. His latest book, Crime and Refreshment, chronicles how speakeasies became hubs for radical urban revolution during the prohibition era.