[Editor’s Note: This piece was published over a decade ago—in what would eventually become Spacing Vancouver. In light of the ongoing discussion on systemic prejudice, it is here re-published to highlight an example of how prejudice gets physically embedded within the urban fabric of a city…as well as the unexpected implications of such conditions.]

MONOGRAPH

We shape our buildings, and afterward our buildings shape us. (Winston Churchhill)

How does one write a monograph in a field that rarely uses them – and on a subject that can never be complete? The fatal weakness of monographs is their inherent need for completeness. Architecture is often discussed as finite, yet the psychological effects of an architectural object are never complete until the day it is demolished.

By its very nature, architecture structures our experience and perception of the spaces around and within it. As such, it influences how we interpret these spaces and our reactions to them.

The case of Vancouver City Hall is an interesting one. Rarely has it been discussed beyond the superficial aspects of its physical presence. Style. Era. Materials. Details. Yet its location in space and its relationship to the rest of the metropolis – as dictated by the circumstances of its creation – structures relationships that have had a much greater impact on the development and growth of the city.

This article discusses how the values of fear, racism, and economic segregation created an architectural monument and how that monument, in turn, influenced the perception and development of Vancouver.

In short, it is how a building created a city.

MARKET HALL

Between 1894 and 1931, the civic government is housed in the market hall located near the downtown business at the intersection of Main St. and Hasting St.—the intersection of several immigrant-dominated neighbourhoods as well as the hotel district that housed dock-workers and transient visitors. This causes much discomfort among civic officials and upper- and middle-class (caucasian) voters. In response, numerous plebiscites are held between 1912 and 1934 for creating a new City Hall away from the market site. The “people” agree that the market hall is not the “right” location. In light of the overwhelming support, city hall processes are moved temporarily to Vancouver’s business district in the rented space of the Holden Building.

SITES

Several potential sites for the new City Hall are considered. All of the sites lay within close proximity to the city’s business district – with the exception of the Strathcona Park site, which lay within the suburbs. Many votes are held to choose a site for the new building and, time and time again, the suburban site places at the bottom of the list. The people want their City Hall in close proximity to the banks, retails and institutions that exist within the city center. Various schemes are considered for the urban sites, but none are built.

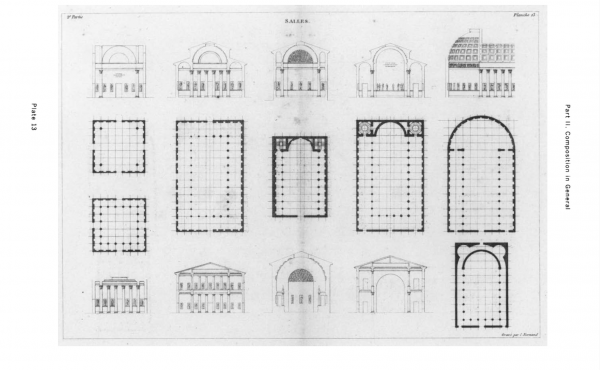

BENTHAM (1748-1832)

Derived from his brother’s concept plan for an easily supervised Military School in Paris, English philosopher Jeremy Bentham creates the Panopticon – the ideal prison building. The concept driving the design is to allow an observer to observe a large number of prisoners without the prisoners being able to tell if they are being observed or not.

The architecture is simple – a central tower surrounded by an annular building that is divided into cells. Each cell – extending the full thickness of the building – allows for inner and outer windows and backlights its occupant. Thus, prisoners are subject to scrutiny – collectively and individually – by an observer in the tower who remains unseen.

Through conveying the feeling of an invisible omniscience, the prison requires few staff. It is the most economical solution for building costly prisons – permitting the fewest number of guards to “observe” the largest number of inmates.

ASYLUMS

The architecture of control reaches its apogee in the late 1800’s as the rising popularity of the Panopticon instigates concepts of the importance of architecture as a moral agent. This is clearly reflected in the design of asylums and prisons where control, surveillance and psychological reform are seen as interrelated phenomena.

The purpose of the architect is to create the illusion of freedom within an ever-tightening blanket of detention and security. Space and form are manipulated to be a moral force in the physical and psychological restraint of inmates, creating order from chaos.

MCGEER

Civil, social, and financial uncertainty abound, as high unemployment rates and bankruptcy become the norm during the Depression. Amidst the turmoil, a new mayor – Gerry McGeer – is elected with promises of restoring order to the city. Given that Holden Building was still being rented for civic uses, a significant part of restoring this order is to construct a City Hall – as it would provide employment and foster civic pride:

“we must drive the money changers out of the temples of government and put the spirit of Christ in charge. By such changes the sovereignty of usury can be overthrown and elected representatives of the people may become the rulers of the “economic bloodstream of the nation.” Responsible government as an expression of Christian Democracy may then be maintained.” (McGeer, The Conquest of Poverty, i-ii)

MANIPULATION

The initiation of the City Hall project in 1935 overlaps with local protests marches, strikes, vandalism and damage to private property. As a result – and in blatant disregard for public opinion—McGeer manipulates the Town Planning Commission into approving Strathcona Park—at 12th and Cambie St. – as the site of the new City Hall.

With that simple action, the future direction of Vancouver’s development and how it is to be perceived is sealed.

The announcement provokes widespread outcry. In a shroud of lies and deceit, McGeer deflects criticism and accusations from the local residents and associations. Arguing that the choice of site celebrates the recent amalgamation with South Vancouver, he silently plans to test Bentham’s concepts at the scale of the city—Benthamian urbanism.

REFUGE

The location for the new City Hall is placed out of reach from the working-class and immigrant people-centered within the downtown core, as well as the banks and credit companies McGeer criticizes as being immoral. The motivations behind his actions are clear. In a clear break from the classic model of civic centers, McGeer seeks refuge from the diversity of urban life within the homogeneity of the suburbs.

INTENTIONS

This is taken one step further as the Strathcona Park site leaves little space for anything more than the building itself. McGeer’s intentions include putting an end to the traditional notion of a civic center; the elimination of spaces of assembly and protest – the elimination of public space.

In that spirit, the building is landscaped with a narrow driveway encircling the building, an act that solidifies McGeer’s allegiance to the suburbs. Located 20ft below, at the base of his car podium, McGeer creates a north-facing sloping treed park that lies within the shadow of his imposing building – a front yard to his suburban palace. McGeer’s vision is actualized —the ultimate suburban monument—a celebration of fear, racism, and economic segregation.

PANORAMA

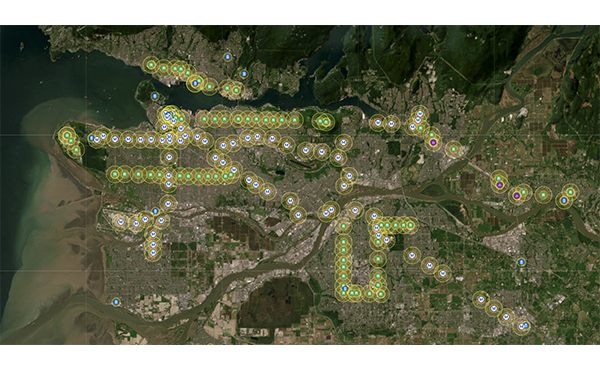

The prominent site, on a hill overlooking the downtown peninsula from the other side of False Creek, allows McGeer and other municipal workers panoramic views of the assailed areas of downtown and of the low-income neighbourhoods of the east end. From above, those who run the city can inspect their domain. Blatantly aware of the natural limits of the urban downtown core, urbanity is to remain contained.

In a twisted distortion of the medieval fortress, Vancouver City Hall is sited and built to protect itself from its own citizens. Like the Panopticon, before it, the monumental City Hall acts as a constant reminder to the surrounding city of the “invisible omniscience” within, effectively leaving the watching to those being watched.

As a platform for the detached surveillance of the urban life that was contributing to its success, the creation of the City Hall is Vancouver’s urban lobotomy – separating the two hemispheres of its existence.

VISION

Gerry McGeer sees his monument built and is replaced as mayor shortly thereafter. Yet his vision and values become the basis for the development and growth of Vancouver for the next 70 years. McGeer dies August 11, 1947.

CONVERSION

In the 1970’s, the City embarks on one of the most ambitious urban experiments in North America. Until the 1960’s, the central area of Vancouver typifies the structure of other North American cities. It is comprised of a downtown area that accommodates financial and commercial functions, a linear belt of obsolete manufacturing-related functions ringing the perimeter of the peninsula, and old residential (working class) neighbourhoods with small apartments, rooming houses, etc.

At a time when Central Business Districts are typified by a monocultural office-based economy, the City of Vancouver set its gaze on the downtown peninsula – turning a blind eye towards the many other neighbourhoods of which it was composed. This act has yet to change. More specifically, Vancouver embarks on a journey to convert False Creek North from an obsolescent industrial wasteland into a mixed-income, diverse residential landscape. This is the first of many interventions that would radically alter the urban core and, ultimately, set Vancouver on the pathway to fame.

This heroic act is made possible by the physical and psychological detachment of McGeer’s City Hall from the urban core. With no fear of immediate consequences to those who govern, Vancouver is allowed to embark on this urban experiment and become North America’s most successful post-industrial city.

ROBSON

Overlapping with the transformation of False Creek North is the design and construction of the New Law Courts by renowned Canadian architect Arthur Erickson. Named Robson Square, the complex connects three downtown city blocks – bridging over one street and burrowing below another. The original courthouse, built in the early 1900’s, provided citizens with a formal public square abutting its main entry – on the north side of the site. It also served as the city’s primary space of assembly.

The new design calls for the conversion of the old provincial courthouse into the Vancouver Art Gallery. The north entrance is closed off in favour of a south entrance and a new courthouse is built a block south of the original. Replacing the original square, Erickson designs a series of interconnected, planted platforms that are ultimately detached from the surrounding streets.

In keeping with McGeer’s values, the last remaining public spaces – adjacent to a significant governmental institution – is effectively destroyed. Subsequent changes to the space further degrade its original usefulness. Citizens must settle for assembling and protesting under the aged eyes of Emily Carr and Picasso.

TRANSPO

To mark the city’s 100th anniversary and the centennial of Canada’s first transcontinental passenger train to arrive on the shores of the Pacific Ocean, Vancouver officials and the government of British Columbia toy with the idea of hosting a great festival of art, culture and history. Given that Vancouver’s history is intrinsically linked to milestones in transportation – the theme of the event is to center on transportation and is named Transpo ‘86.

In 1980, the British Columbia Legislature passes the Transpo ‘86 Corporation Act, paving the way for the most influential fairs in Vancouver’s history. It eventually becomes clear that the event is to be a world exposition. Thus, Transpo ‘86 changes names to Expo ‘86. Originally, the world’s fair is to be held on the grounds of the Pacific National Exhibition, several kilometers away from the downtown core. When the Pacific National Exhibition grounds are deemed too small for a World’s Fair, the Transpo ‘86 organizers set their sights elsewhere.

During this time, Vancouver is negotiating to buy back land on the north shore of False Creek from the Canadian Pacific Railroad. A century of heavy industry turned the area into an eyesore. The fact that the area is seen daily from the windows of the City Hall makes the issue more pressing. In 1980, the Bureau of International Expositions unanimously vote in favour of Transpo ‘86 and suggest that the fair be located on the False Creek site. It is to be a critical extension to the False Creek North experiment underway since the 70’s. City officials are extremely content with the situation as their “eyesore” will be cleaned up and they can survey the grand event – detached – from across the waters of False Creek. Unknowingly, as they happily trot from pavilion to pavilion, flocks of tourists are under the constant gaze of the City. Urbanity under surveillance.

CONCORDE

After the fair, developers bid on the site. The lease for the entire 175 acres goes to Concorde Pacific development team based in Hong Kong. It is to be sectioned off into neighbourhoods – each with it’s own distinct theme and architecture. The 30-year urban housing plan is to be finished in 2016.

As of 2008, approximately 95% of the expo site has been fully developed into housing, retail and park land. Within this colossal development, recreational public space is strung in a necklace along the shores of False Creek. None of significance are created within the city proper, ensuring that the public remains under the watchful eye of the City Hall.

NEEDLES

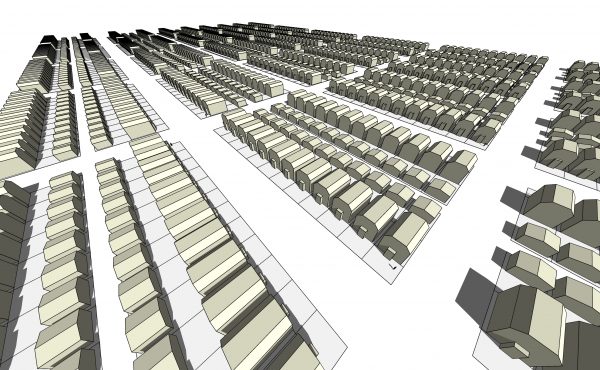

1991 marks a momentous year in the development of Vancouver. After years of research and discussion, the city’s revised Central Area Plan (CAP) is released and approved. It calls for the strategic reordering of the downtown core in favour of a mixed-use, high-density residential environment. Destruction ensues as older neighbourhoods, historic buildings, and traditional public open spaces are replaced by glass needles on podiums. In keeping with McGeer’s vision, open spaces – potential spaces of protest and civic opinion – are largely eliminated from the city core, pushed out to the peninsula’s residential perimeter.

Detached from the urbanity between the skyscrapers, the decisions of municipal officials do not engulf them – as they would in most other cities. Instead, they watch from their windows as the peninsula rises against the backdrop of the north shore mountains. They orchestrate the creation of the skyline through the frames of their windows in anticipation of the camera lenses of visiting tourists.

BENTHAM’S CITY….

As the gaze is centered on the downtown peninsula, issues in other Vancouver neighbourhoods gain little attention—for the Eye can only look at one place at a time. Around City Hall, the largely suburban environment remains largely intact with building heights capped as to not block the view to and from the Great Eye.

Curiously, Vancouver City Hall itself remains largely the same despite the radical shift in values and growth since the buildings creation. Do aspects of Gerry McGeer’s sinister values still ring true in this celebrated metropolis? As the Panopticon was to be the ideal prison, is Bentham’s City to be the ideal city of tomorrow – as many would have us believe?

Only time will tell…..

***

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements across Scale and Culture. He is also an educator, independent researcher and designer with personal and professional interests in the urban landscapes. His private practice – Metis Design|Build – is an innovative practice dedicated to a collaborative and ecologically responsible approach to the design and construction of places. You can see more of his artwork on his Visual Thoughts Tumblr and follow him on his instagram account: @e_vill1.