The global housing crisis is a challenging and multi-faceted problem. Part of the solution, already successfully employed by universities, the campus model of residences could find efficient and cost-effective application off-campus.

Unaffordable Housing, Insecure Housing and Homelessness

Growing populations, an ever-increasing economic divide, mass migration, and global warming have exacerbated the global housing crisis, which has forced people into impermanent homes such as refugee camps, tent cities, inadequate or outdated buildings, living in their cars and campervans, or on the street.

Cities respond with a variety of approaches: funding the construction or purchase of apartment buildings, allowing motorhome parking, erecting temporary prefabricated multi-residential buildings, encouraging densification legislation (laneway homes, condo tower height easements), homeless shelters, and opening parks to informal housing.

In addition to various levels of government, often entangled, a number of players crowd the field, including landlords and for-profit developers, NGOs, churches, cooperatives and grass-roots activist organizations. These groups form partnerships in different ways, some more effective than others. It is difficult to balance the complex needs of diverse communities with a profit motive.

Inventive solutions

Most often, the people themselves come up with their own solutions. Rather than being lumped under the generic and pejorative term of “homeless,” these user-designers build extremely inventive dwellings. Japanese artist/architect Kyohei Sakaguchi has studied the “Zero-Yen House,” a phenomenon which can be highly mobile, making creative use of cardboard, solar power, cell phone technology and so on.

A variety of 20th-century housing experiments have been examined by the Vancouver-Vienna artist collective, Urban Subjects. The model of social housing first developed in Vienna as a response to the severe housing crisis that followed WW1 has evolved into a highly successful model of social housing that makes Vienna one of the world’s more affordable cities. American artist and community organizer Rick Lowe started Project Row Houses where housing, art, and community are the foundation for revitalizing depressed inner-city neighborhoods.

Institutional Response

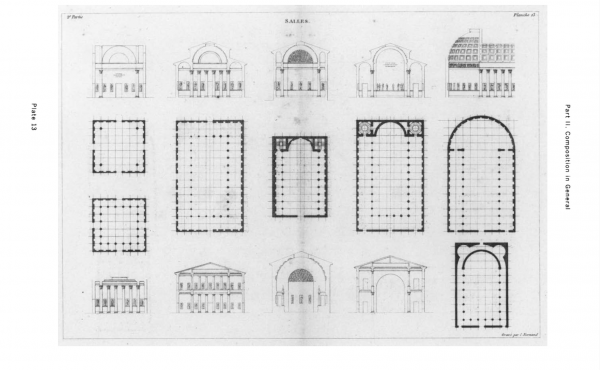

Larger scale government approaches have met with qualified success. The influence of Le Corbusier looms large in this history. In Socialist Europe, all housing was social housing, typified by vast, uniform, and repetitive tracts of high-rise apartments. This model was imported to New York in the 1950s and called “urban renewal.” Known more commonly as “the projects,” these became famously dysfunctional hotbeds of crime and social deterioration. Many were pulled down after only twenty years. Urban advocate and thinker, Jane Jacobs is credited as a visionary who showed a more successful and people-centred way to urban densification.

What we need today, especially in a city like Vancouver, is more institutional social housing that can address the complex needs of diverse communities. These include single parents, people facing addiction and other health issues, multi-racial communities, the elderly, low-income people, those transitioning from the prison system, and so on.

Successful stories have been achieved by non-institutional housing communities, such as Indigenous housing, co-operatives (public and private), veterans groups, non-profits like the Portland Hotel Society, specializing in the “hard to house,” and Atira, which builds and manages safe housing for women. Retirement homes, often operated by cultural groups like S.U.C.C.E.S.S., church-sponsored housing, self-directed intentional communities and co-housing collectives each make their own contribution. One exemplar is the Hunziker neighbourhood built on a former concrete factory in Zurich. Created with a participatory process, Hunziker offers living and working situations for 1200 residents in a variety of configurations and forms of tenure. The design by Duplex Architecten’s offers a range of individual and collective retreats.

The Post Secondary Housing Model

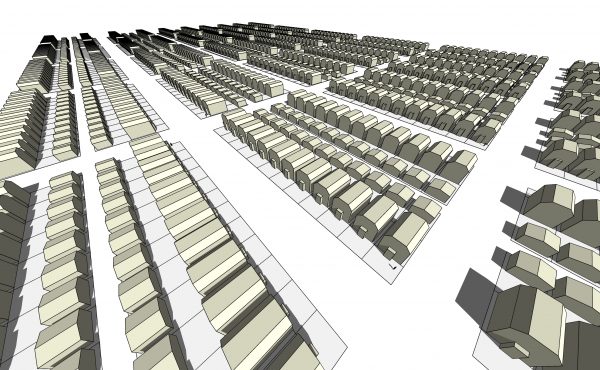

Social housing in British Columbia is still fairly conventional in form: the focus is on the individual unit. Each is still, in essence, a shrunken, single-family home with a prescribed sleeping, living, cooking, and eating areas, all of a standard size. Higher education campuses are where the real housing innovation is happening.

Campuses are cities in miniature, but they have advantages that cities don’t have – they are centrally organized, centrally administrated, and centrally funded. Plus there is an overall sense of common purpose. These conditions allow post-secondary campuses to act as test-beds for what cities could be and do.

For example, Lundgaard & Tranberg Architects’ Tietgen Dormitory in Copenhagen creates a sense of community and safety by wrapping individual rooms around a generous communal courtyard. This safe space is filled with trees and places for residents to gather in small and large groups. Shared indoor and outdoor cooking and eating areas overlook the courtyard below. At the ground level studios and workshops foster community and shared experience. Private rooms face away from the courtyard to the campus.

The Skeena House by Vancouver practice PUBLIC, takes lessons from the Tietgen Dormitory. It is comprised of shared social and workspaces on the ground floor. Together with other housing buildings on campus, it frames a generous green space. Upper floors house private rooms as well as shared cooking and eating areas.

And here is what campus’ do differently: Skeena House works together with other buildings to enliven public space.

All front doors and shared social spaces open directly onto the campus green space, reinforcing its activity, safety, and viability. Together each building is more than the sum of the parts. They create a neighbourhood. In addition to this, Skeena is the first on-campus Passive House residence built in Canada. It is so energy efficient that in the height of winter, students’ bodies provide nearly a third of the building’s heat. It is a win-win.

Through design, campus housing promotes a sense of community among people a diverse population, often multi-ethnic, multi-lingual, and multi-generational, and who come from a range of economic backgrounds. Residence buildings are efficient, durable, and affordable to build. This model could be seen as a direct response to the crisis of homelessness. According to government research statistics Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, the overall cost to society of housing is considerably less than the cost of homelessness.

***

Brian Wakelin is co-founder of PUBLIC: Architecture + Communication.