‘Starting Over’ Part Two: Self Knowledge

- There was a commonwealth in understanding the city as a shared resource. It was shared by those who worked in its engine room. Dust and impurity in the gears needed lubrication of the most sticky bits. It worked (mostly) by meeting in the middle of the mesh.

Square holes round circles

- Where you start to go is rarely where you end up. Even going around in circles, the ground shifts under your feet. By 2020 a square foot of buildable area cost more than the cost of construction. In 1990 the cost of construction was much more than the land.

- Digging deep is necessary to effect a worthwhile result. It used to matter where you put stuff. That is called City Building. Touts now tout for more stuff to be put anywhere. This is called Building a Racket.

- Back then those reluctant to think told us the only way to prepare the inner city for the middle class was to provide above-grade parking.

- Our response was to perfect storing them below-ground while praying for rapid transit (although bicycles were barely thought of).

- Downtown was gridded off with 120 foot deep lots. Regardless of the driver’s skill, it had been determined that the width needed for 4 parking bays with 2 parking aisles was 116 feet. This leaves room for a 10-inch foundation wall and perimeter drain at the front and rear of the lot.

- A ramp gradient of 12.5% enables the most efficient way of stacking barrier-free storage underground, whether for cars or mushroom farms, or whatever.

- This storage costs 10 times more than taking acres of worthless gravel and transforming it into asphalt with a few shrubs. That was the price of letting people think they were downtown somewhere other than North America.

The not-flat-earth society

- No street is flat. This is fortunate unless you want the rain to run indoors. Raise the ground floor to tabletop height above the sidewalk, and set it back a lounge chair or so from the street.

- Now you can look over the hedge and passers-by all the way over the parked cars across to the street trees on the other side. This is where the push came to shove, and the skimpy but heavy-lifting streetwall, got livability built.

- It may be familiar from your trip to a European balcony above the café. Slightly more obscure from the upper veranda of a Singapore shophouse. But foreign to perception shaped by the car in the driveway of a split-level rancher.

- What was not initially so obvious was how to frame this so that someone would borrow millions of dollars to get it built.

- The heavy lifting of the streetwall of townhouses was a case of musical chairs in the Russian roulette of maximizing floor space from the zoning.

- Of equal import was this distance between buildings. You and I know this is about livability, the feeling of well-being and privacy while being glanced at by hundreds of strangers.

- But this was actually about the cost of parking.

Fine lines

- One of the finest lines, related to but beyond the fantasy of silence, is the line of sight from my prying eyes to yours. This would determine how far apart tall buildings should be, up above the street tree modesty of the Yaletown streetwall

- The high tech approach to resolve this was the white pages. Phone calls were made all over North America to find out the rules for how far apart residential towers had to be. Only Calgary and New York turned up any codification, one 30ft the other 50 ft.

- So 50+30 seemed like a good number, the more so when combined with the mathematics of building height, and the need to unfetter development advantage in order for beneficial things to happen.

- Such is the difference between chasing the ball around the field of play and kicking it between the seats in the stand.

Such great heights

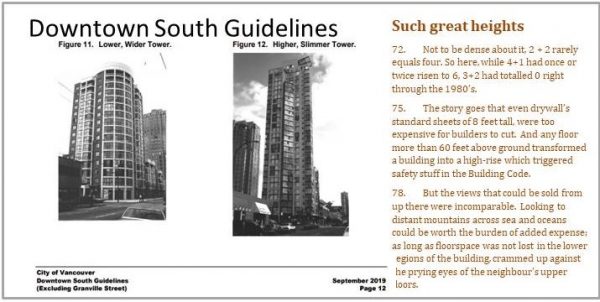

- Not to be dense about it, 2 + 2 rarely equals four. So here, while 4+1 had once or twice risen to 6, 3+2 had totaled 0 right through the 1980s.

- While rhetoric blazed whether development should be permitted 5 or 6 times the floor space of its site area, the maximum height for Downtown South was a fix at 300 feet.,

- Part in obeisance to the ‘really tall’ 450-foot towers marking the Central Business District, and because no-one could afford to borrow to build any higher to serve a market that did not exist.

- The story goes that even drywall’s standard sheets of 8 feet tall, were too expensive for builders to cut. And any floor more than 60 feet above ground transformed a building into a high-rise which triggered safety stuff in the Building Code.

- All in all the Taj Mahal was more economic than an 8-storey condo. So a 300-foot maximum meant every building really wanted to be 33 storeys tall when it grew up.

- Then was a time of hierarchy, the cut of cloth and close ties still mattered. Not like now where the margins proudly reign (this a measure of profit rather than the power of the marginalized).

- But the views that could be sold from up there were incomparable. Looking to distant mountains across sea and oceans could be worth the burden of added expense; as long as floorspace was not lost in the lower regions of the building, crammed up against the prying eyes of the neighbour’s upper floors.

Tipping point

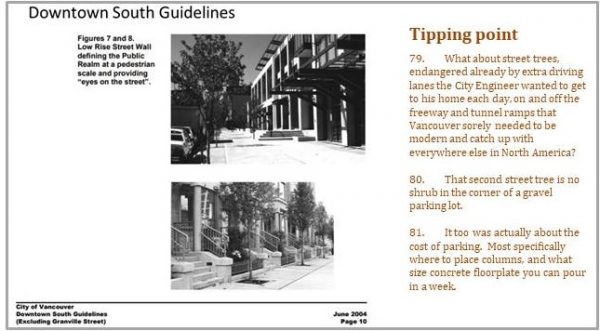

- What about street trees, endangered already by extra driving lanes the City Engineer wanted to get to his home each day, on and off the freeway and tunnel ramps that Vancouver sorely needed to be modern and catch up with everywhere else in North America?

- That second street tree is no shrub in the corner of a gravel parking lot.

- It too was actually about the cost of parking. Most specifically where to place columns, and what size concrete floorplate you can pour in a week.

- If the buildings were set back 7 feet from the street, and 30 feet from the lane, with a minimum pair of 40-foot setbacks between developments, then the prying windows would be 80 feet away from each other, and the risk of murders and suicides would be correspondingly lessened.

- If the building is set back an extra 5 feet from the street, and another 5 from the lane, giving a 90-foot separation ‘front-to-back’, then the most efficient concrete can be poured for the tower above, with a second tree squeezed in the extra gap.

- And trees and traffic lights, even on Pacific Ave, would enable pedestrians and their children to cross streets without the use of a car.

- Etc. Etc. The picture should be getting clear. No matter how one cantilevers the argument, there has to be poetry in the numbers to restore balance at the tipping point.

How long is string?

- To start answering this needs a jump ahead of 30 years to what would be a red herring, if not for the “I want what they got” imperative of real estate practice which always aims to get more than anyone else.

- In 2014 we rezoned a parking garage on a site with a permitted density of 9FSR to replace it with an office of 25FSR. We sensitively fitted a unique pivoting form into its context that gently guided eyes and pedestrian flow to and from Waterfront Station, spinning inches below the constraining view corridor.

- On this city block, two large office towers and a skinny 16-storey infill already stood. Within a decade, this new tower and two more 25FSR towers are being built, each presumably sited accordingly to enduring urban design principles.

- Back in 1990, you could scarcely build a 2-storey commercial building in Vancouver to save your life.

- But folk sure had enjoyed coming to visit that EXPO 86 on the backside of Downtown. Maybe some hipsters would come here to live and party (or flee insurrection in their homeland), and some empty-nesters would sell their empty houses and live high above the action downtown.

Home field advantage

- Even at 80-foot spacing, there could be 6 towers per block at precious little above 13 storeys each, and each one blocking the other’s views. Titchy floorplates 6,000 square feet or less, of which 1,800 feet of elevators, exits, and balconies would steal from the saleable area.

- The result would be shoulder-to-shoulder, like Stalin’s Russia without the terracotta friezes, or Kowloon without the air conditioners. But there would be little problem preserving the view corridor from the Hemlock on-ramp.

- It was then a fact universally acknowledged, that a concrete crew wanting an efficient pour cycle, must be in need of a floor plate of approximately 7,200 square feet.

- Setting a minimum frontage of 175 feet for corner sites and 200 feet for interior sites, a practical depth of around 75 feet for any tower, and that 7,200 square feet pour, the separation between towers on any block face would remain abundant with plenty of light and air for anyone.

- And so, between each set of four streets, a playpen was pitched with no more than 4 stand up sandcastles on a city block, no matter what any supervising adult might say.

- Playing was a serious game. But it did have the luxury of not being about luxury. Which is what spoiled things later.

***

- Starting Over – Part 1

**

Graham McGarva is a Metro Vancouver architect, urbanist, and poet.