This is a story about a little fast food shop for sale and its challenges. It’s also a story of what these obstacles mean for both commercial services along the new Broadway subway and for young wage earners hoping to occupy a home near this new subway.

It’s all linked, as we shall see.

The business for sale is Donky Chicken. I must admit that I have long been intrigued by the unusual-sounding name. I did learn it’s part of a chain started in Korea. But I have yet to sample Donky Chicken.

I’ve also wondered what it would mean to own — or buy — the place.

Perhaps you have seen this emporium. It is located close to the intersection of Broadway and Main, and if you are interested, the business can be had for $270,000, fryolators included.

Sadly, this price doesn’t include the monthly cost of the rent and taxes, which is really what I want to focus on. The owner of Donky Chicken, you see, isn’t selling the building or the land, just the business on that land.

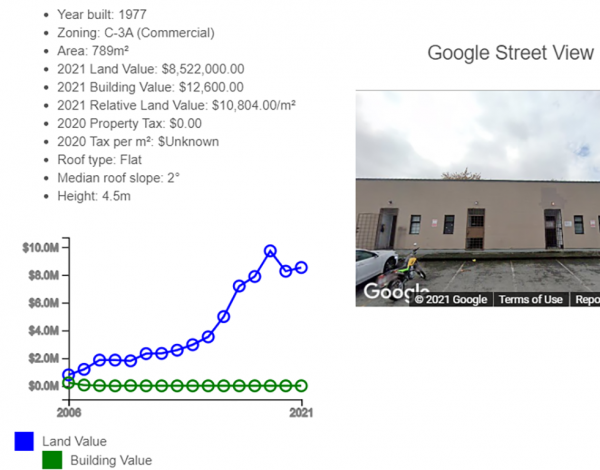

The real challenge for Donky Chicken is not the value of the building, the building’s value is slowly shrinking according to the assessors. The problem for this business is the value of the land it sits on. The dirt under the whole building is now worth $8.5 million according to the assessor’s office.

One big problem for Donky Chicken is the way rents are calculated in Vancouver. Donky Chicken has to pay rent for its share of the building, but also has to pay the property tax for the land it sits on and the building it’s in (it’s called a triple net lease, which shifts the risk of tax increases off the shoulders of owners onto the shoulders of renters).

This is really a drag because the landowner has passively gained the 1,000 percent increase in the value of the dirt under Donky Chicken, while his tenants have the pleasure of paying the ever-increasing tax bill. At the city’s commercial “mil rate” Donky Chicken will probably be billed about $18,000 in property tax. That’s on top of around $24,000 in rent for this 1,000-square-foot shop. Ouch. You might think this big increase in land value is due to a much-improved business environment on that corner. But the real estate folks will tell you that at that rental rate the value of the entire 6,000-square-foot building and land is worth only $1.9 million, a small fraction of its $8.5 million assessment. What gives?

This parcel is presently at its full allowed size without a zone change. So, its value should not reflect any speculative value. But of course, it does.

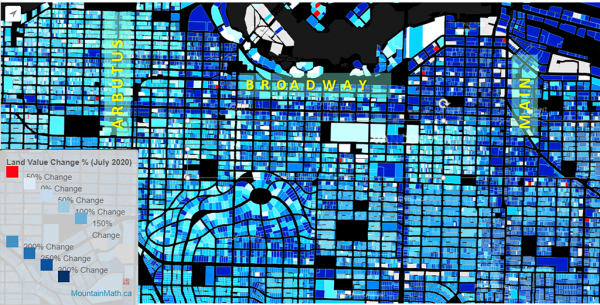

Residential space is already valued at over $400 per “buildable” square foot in this area, so the assessed value of Donky Chicken’s building definitely reflects an assumption that the “highest and best use” of the land under Donky Chicken would be for new condos. Tax assessments are not based on existing use but the recent comparable sale price of similar parcels nearby. Those already elevated sales prices are likely elevated in anticipation of the new Broadway subway, and the associated Broadway Plan — a plan which calls for massive density increases along the subway line. Between Main Street and Arbutus, land value has inflated by between 300 and 1,200 percent in response to these initiatives in just a few years, (Commercial land in other parts of the city has gone up too, but not nearly as much: roughly 200 percent.)

This amount of new value, assuming these increases are consistent along this stretch (and they are) would amount to a subway-induced land value increase of over $4 billion. Interestingly, that increase in land value is appreciably more than the cost of the subway at approximately $3 billion.

This kind of price jump is nothing new. This is a naturally occurring phenomenon when very expensive taxpayer-funded infrastructure is built. Land value near it usually rises by more than the cost of the infrastructure itself (Nobel prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz named this his “Henry George Theorem.” We have seen mention of this same Henry George in these pages).

City hall did make some effort to get ahead of this effect. In 2019, anticipating this land price inflation, the city imposed a new fee that only applied to the Broadway Corridor. The Development Contributing Expectation fee, or DCE, was passed to put a damper on subway-fuelled land speculation frenzy and was set at $340 per square foot for each new square foot of interior space above what was allowed under current zoning. The intent was to quell speculation by signaling the city’s firm intention, well ahead of time, that a big development fee was coming so that developers would not pay too much for the land. The idea is to tax most of this taxpayer-funded increased land value “land lift” away from the overstuffed pockets of land speculators and stream it towards public benefit instead.

Apparently, it hasn’t worked. Land price increases along the corridor are still outpacing land price increases anywhere else in the city. By a lot, suggesting that this fee was set too low or that the “market” doesn’t believe the city will, in the end, actually levy such a fee.

In light of the above, this little story of Donky Chicken has a broader and more serious aim. Its purpose is to show how our decisions about infrastructure and the land uses that end up supporting it, have the tragic consequence of putting our local merchants out of business, while making land far too costly for developers to provide affordable housing.

Only the land speculators get the big payday. And the speculator is typically not the current owner of the land, but an investor who sniffs out an increase in value coming and makes the current owners an offer they can’t refuse.

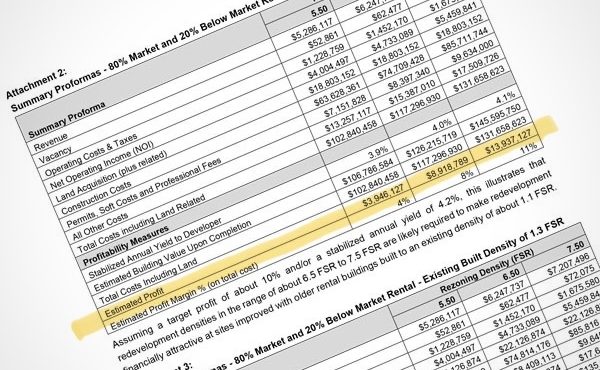

The land price inflation that the subway has already unleashed means that there is no way a market developer will be able to produce housing, either rental or condo, along the corridor that will be affordable to average city wage earners.

The cost of land is already too high for developers to rent or sell at prices even remotely close to average city wages (new one-bedroom apartments along the corridor are already renting at $3,000 per month).

Only the top ten percent of Vancouver’s earners will be able to compete for this space.

The absolute biggest beneficiaries of the subway project are men and women who didn’t fry one chicken wing or produce one single apartment unit. They will be the land speculators, whose fantastic gains will remain largely untaxed.

And the next generation hoping all that new development along Broadway will deliver lots of affordable food and housing? Their goose is cooked.

***

This piece was originally published on the Tyee.

**

Patrick Condon is the James Taylor chair in Landscape and Livable Environments at the University of British Columbia’s School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture and the founding chair of the UBC urban design program.