Author: Ralph Segal

With the City’s current Zoning Map as an initial regulatory reference, Vancouver’s contemporary approach to planning, urban design & sustainability, ever-evolving since the 2000s, has pursued comprehensively planned and designed neighbourhoods, districts and precincts to achieve complete communities while addressing an array of city-wide planning objectives. This approach to city building, responding to major development initiatives, “mega-project” sites and long-range policy and economic issues, has focussed in the last decade on integrating significant rental and affordable (including social) housing throughout the city.

It is as valid an approach today as it was in the past in its delivery of notably increased housing density at well-served locations able to absorb in terms of urban design, greater building scale while creating enhanced public realm and parks with integrated community facilities. Just a few examples of several hundred outside the downtown are:

- Cambie Corridor -pursuant to subway station precincts:

- Cambie & 41st. station: Oakridge Park + Oakridge Transit Centre site + Heather Lands + Little Mountain + Oakridge Town Centre = “Municipal Town Centre”,

- Cambie & 49th & 57th stations: Pearson/Dogwood & Langara Gardens sites,

- Cambie & Marine Dr. station: multiple high density housing developments; plus-

- Olympic Village;

- East Fraser Lands;

- Skeena Terrace;

- Rupert & Renfrew Station Area Plan: currently underway.

A list of all such examples, many pages long, would reveal the inherent value of best urban design practices in housing development. But the glaring absence of senior governments’ essential financial contribution to the pursuit of such affordable housing solutions has been a huge impediment.

The tailored-for-Vancouver core planning, urban design, sustainability and housing policy principles that produced the above body of work can be further strengthened, focussing on affordable housing solutions while still maintaining a suitably compatible “fit” within neighbourhoods into which new development is inserted as well as minimizing tenant displacement. An unforeseen outcome of Vancouver’s internationally lauded urban design and development has made Vancouver a highly attractive destination for domestic and foreign real estate investment, generating repercussions both positive (increased development activity and housing supply) and negative (counter-productive land speculation).

But now Council has approved the Broadway Plan (Vine Ave. to Clark Dr./1st Ave. to 16th Ave.) and the Vancouver Plan (effectively the entire remainder of the city), both of which pursue a substantially different approach that appears to come from somewhere else. This new approach designates expansive areas of the city for major densification and increased heights based primarily on a significantly stretched interpretation of current Transit-oriented Development (TOD) policy whereby transit proximity criteria will now include widespread new areas, most more than 8-10 blocks from arterial bus routes, to be added to present rapid transit (subway, Skytrain etc.) station precincts.

Both Plans dismissively abandon established neighbourhood contexts and scale based on the false narrative that our housing affordability crisis can only be solved through major pervasive density and height increases that create an over-supply of units but imposes a far more impactful tower built form on the liveability of many areas of the city, not to mention the dubious environmental sustainability of tall towers.

While the Broadway Plan correctly calls for notable densification on Broadway proper around subway stations to further enhance this street’s already important role, most disturbing is the Plan’s significant densification and height increases north and south of Broadway, promoting an influx of 20-storey towers to replace existing low rise apartments. This puts at serious risk many of the existing 19,600 rental units which constitute 25% of the city’s inventory, most of which are affordable.

If only a quarter of these existing units (4,900) were lost to redevelopment, then assuming (generously) under the Plan an average of 35 affordable units in a typical new rental development (20% required to be affordable), it would take approximately 140 new rental developments (4,900/35 = 140) just to replace those existing affordable units lost in these areas alone, without a single NEW affordable rental unit added! Did this rudimentary calculation factor into Staff’s forecasting of possible Plan outcomes?

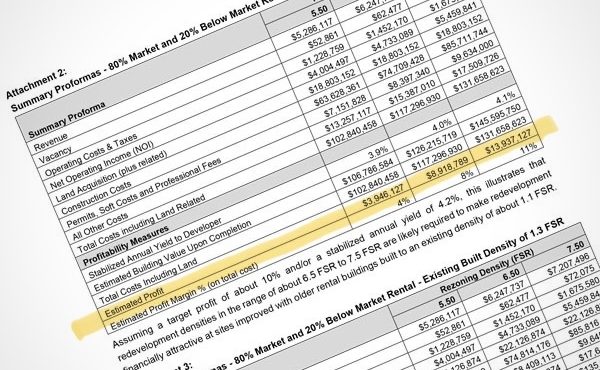

Ironically, it is such rampant, indiscriminate densification and height increases that would trigger far greater land speculation, undermining the intended delivery of substantive affordable housing as a result of predictable skyrocketing land costs. The planning and urban design dictum, “Form follows Function” (Function benefitting all) would degenerate into “Form follows Finance” (Finance benefitting land speculators and developers).

To be clear, in my 25 years dealing with development proponents in my role with the Planning Department, I gained a healthy regard for developers’ practical common sense, often inventive (surpassing City aspirations!) approach to their developments. But they are in business and when handed a huge density bonus under the Broadway Plan (eg. 4+ times the presently zoned density) which they surely have had a voice in influencing, they will take it!

The Vancouver Plan devotes but a half page (Direction 1.7 p.88), with two terse paragraphs of text, to this issue of land speculation, giving short shrift to the reality that the Vancouver Plan’s pervasive increased density and height provisions would seriously accelerate the resulting escalating land costs. This phenomenon, already commenced, would encourage the development community to seek even further up-zoning to cover such additional upfront costs. Indeed, numerous projects already approved under existing policies with sites long ago assembled, appear to be on hold. Are these developers, taking note of the greater density incentives in both Plans, strategizing how they could re-negotiate further increased density and height, citing these pervasive new Plan provisions as precedents?

No one disputes the desirability, indeed the need for a comprehensive Vancouver Plan. And two components of this present Plan, originating from work that commenced almost a decade ago, should be acknowledged and reinforced. The Plan’s “Municipal Town Centre” (MTC) precinct surrounding the Cambie & 41st Cambie Line station (see earlier – Cambie & 41st. station: for description) accommodating high density, mixed-use development is one of our best examples of Transit-oriented Development (TOD) already approved, simply re-named in the Vancouver Plan.

And the Plan’s Direction L1.8: Multiplex Areas (p. 67 of Vancouver Plan) replaces city-wide RS zoning’s low-density single-family housing with “gentle densification”. Increasing density to, say, 1- 1.2 FSR to improve the viability of small project proformas, allows for a more advantageous mix, including secondary suites, of up to 6 units per lot.

This would expand on duplex and laneway infill units now permitted, creating a substantive increased housing potential throughout the considerable land area now zoned RS. Further, a streamlined development permit process with well-illustrated development guidelines would provide the incentive for timely delivery of highly “green” ground-oriented housing in a compatible 2-3 storey “neighbourly” built form on existing lots, avoiding (precluding?) land assembly with its predictable crippling land speculation and eliminating the costly elevators, exit stairs, common corridors and underground parking required for apartment buildings.

This harsh critique of the Broadway and Vancouver Plans has nothing to do with Nimbyism. Rather, it is about the short-sightedness of Staff and then Council discarding a number of highly relevant neighbourhood plans. It is about failure to acknowledge that increased housing density in the right locations, so many of which are already identified in existing rental policies (eg. “Secured Rental Policy”), numerous neighbourhood plans that can be further expanded, and a multitude of approved major spot rental rezonings that, taken all together, have been shown to exceed all housing supply targets to 2050.

It’s about addressing this city’s long-term future with workable solutions to affordable housing that maintain the liveability, urban design and public open space attributes, left undefined in both Plans, that are to serve Vancouverites, including those arriving in the future who would have chosen our city for its high-quality urban environment and neighbourhoods as well as its affordability. We can do better.

***

This article was originally published on Viewpoint Vancouver.

**

Ralph Segal is the former City of Vancouver Senior Architect Urban Designer Development Planner.

2 comments

Can the writer point to Vancouver having an over-supply of units? And if he’s talking about a zoned capacity, can he show a moderately affordable city where the zoned capacity isn’t multiple times the existing units?

Modern zoning radically decreased zoned capacity, and that’s what actually creates the land speculation – future density is artificially choked, and that creates a speculative market. This article seems to suppose that if the gap between the planned growth and the planned capacity was closer to 0 and fewer sites could support density, that would create less speculation on a site by site basis. But it seems to me that’s an inverse of the actual argument – allowing large scale development everywhere may give many existing landowners a small lift due to latent demand, but the general nature of the uplift means each lot has less competitive advantage.

This respondent appears to draw an incorrect inference from my Broadway & Vancouver Plan critique, that I’m seeking to down-zone areas of Vancouver or prevent any density increase anywhere. Nothing could farther from the truth. I am not aware of a single density reduction anywhere in the last 30 or more years although a few districts’ densities have remained unchanged or very modestly increased (i.e. RS districts have increased from 0.6 to 0.7 FSR). So virtually all Vancouver districts presently have densities that allow for either a modest “zoned capacity” or in numerous cases under specific policy, a major increased zoned capacity intended to incentivize redevelopment (eg. existing policies to encourage rental housing which includes an “affordable” component to address our housing unaffordability crisis).

I am critical of the Broadway Plan’s 4.5 times density increase throughout areas north and south of Broadway because this strategy will provoke the demolition of many affordable rental units in existing low rise apartment buildings, subjecting numerous low-to-mid-income tenants to the severe hardship of displacement while achieving no more than a bare replacement of lost affordable units, NOT a significant increase in total affordable units delivered that might justify such disruption.The Vancouver Plan’s proposed pervasive major increases in densities city-wide will trigger an explosion of land speculation unnecessarily (this phenomenon is already an uncontrolled problem locally) versus a more measured concentration of increased density in close proximity to rapid transit stations and on specific large, well-served sites such as Skeena Terrace.

Rather than debating the machinations of the marketplace to “zoned capacity”, the real issue to be directly tackled is the delivery of affordable housing. In this regard, it should be recognized that private sector/corporate development, constituted to be for-profit, is not ideally geared to be the primary source for affordable and social housing, although it should be tapped to provide a meaningful contribution. It is senior governments’ role to fund and deliver affordable and social housing in consort with the City’s freeing up of city-owned land for this purpose.