How can Canada possibly spend five years and tens of billions to fix the housing crisis, but still have no idea if it’s working? That’s the question raised in a recent report by the federal auditor general.

Canada’s government is in the process of spending $78.5 billion — about $5,000 per family — to fix housing. But it can’t show that money is having any demonstrably positive effect — not in reaching the goal of cutting homelessness in half and not in reaching the goal of supplying hundreds of thousands of housing units for lower-income Canadians.

The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. takes the bulk of the auditor’s heat as CMHC leads the so-called “National Housing Strategy.” But that strategy also identifies roles for Employment and Social Development Canada and Infrastructure Canada. The audit identifies a severe lack of coordination between the departments as a major source of the problem.

What do we even mean by affordable?

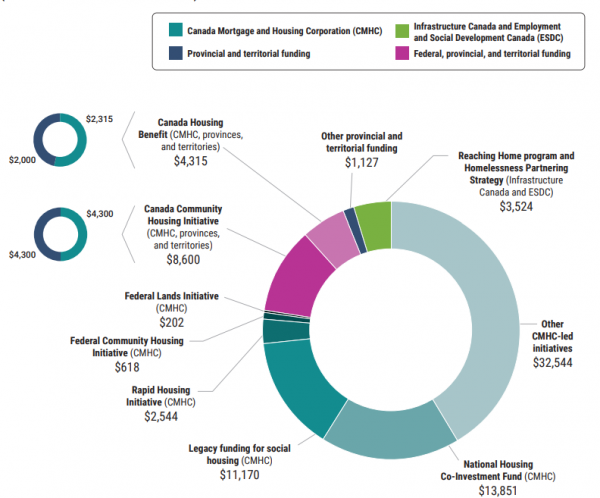

So, halfway through this decade-long plan, what was it supposed to accomplish? The bulk of the $78.5 billion was allocated to build, repair and provide subsidies for housing. The target is a nationwide crisis of unaffordable housing for moderate to low-income Canadians, and its natural result—homelessness. Here’s how all that cash was distributed:

The report is particularly scathing when examining the nation’s Reaching Home program that supplies funding to 62 Canadian municipalities experiencing ever more serious problems of homelessness.

The top related finding about that initiative: “Overall, Infrastructure Canada, Employment and Social Development Canada, and the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. did not know whether their efforts improved housing outcomes for people experiencing homelessness or chronic homelessness and for other vulnerable groups.”

The auditor reveals that little to no evaluation of these programs has been made, and that there is a similarly shocking lack of clarity around who, if anyone, has been responsible for oversight:

“As the lead for Reaching Home, a program within the National Housing Strategy, Infrastructure Canada spent about $1.36 billion between 2019 and 2021 — about 40 per cent of total funding committed to the program — on preventing and reducing homelessness. However, the department did not know whether chronic homelessness and homelessness had increased or decreased since 2019 as a result of this investment.”

The report indicates that the truly big money was not spent on temporary housing for the homeless but on subsidies for the construction of market rental housing under the National Housing Co-Investment Fund.

A case might be made that by creating housing supply higher up the affordability ladder, you vacate, and keep rents lower, for units that very low income or unhoused folks can inhabit. Wonks call this attending to the “housing continuum.” And so the National Housing and Co-Investment Fund supplies loans and grants to both private and non-profit housing providers in the hopes of alleviating our national housing crisis across the low to moderate price range of that housing continuum.

But is it working? Who can say? Wrote the auditor: “We found that the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. did not know who was benefiting from its initiatives. While the corporation knew vulnerable groups were intended to benefit, it did not know whether those groups were actually occupying housing supported by its initiatives. Moreover, it did not measure the changes in housing outcomes for priority vulnerable groups. We also found that rental units approved under the National Housing Co-Investment Fund that the corporation considered affordable were often unaffordable to low-income households.”

The report traced the reason for this confusion to the definitional ambiguity of the phrase “affordable housing.” It said, “We found that the National Housing Co-Investment Fund had a measure for affordable housing that was not the same as the National Housing Strategy overall. The result of this was that rent for approved housing was often unaffordable for low-income households, many of whom belong to priority vulnerable groups. In the strategy, affordable rent is calculated as less than 30 percent of before-tax income.

“In the National Housing Co-Investment Fund, affordable rent is based on rent being less than 80 percent of median market rent. We calculated that rent for units approved under the initiative was typically about 63 percent of the median market rent, which was less expensive than the 80 percent criterion. When we compared rent using the two affordability measures, we found that overall low-income households would have to spend 30 percent or more of their before-tax income on rent.”

All of which is a nice way of saying that the “affordable units” were not really affordable by the Canadian families nominally targeted by the program because “more than 85 percent of Canadian households in core housing need had a before-tax income of less than $50,000. This meant that monthly rent would need to be less than $1,250 to be considered affordable.”

The report concluded, therefore, that very few of the units delivered in partnership with private real estate developers ended up affordable for Canadians experiencing the brunt of the housing crisis.

In Vancouver we are more than acquainted with this bizarre split in the definition of affordable housing. Coun. Pete Fry has tried, so far without success, to change the city’s definition to one pegged to average city dweller incomes rather than calling affordable prices and rents that merely are lower than average in a city with some of the highest housing costs in the world.

What would actually work?

The damning report on Canada’s failure to credibly claim results for its $78-billion program to make homes more affordable and put a measurable dent in homelessness invites the obvious question. What would be a better way to spend that money?

My response starts with the observation that these billions now are spent in “partnership” with private industry in return for largely unaffordable units. I would argue that money better spent to increase support, lapsed since the 1990s, for non-market housing such as co-ops. Currently, funds to support new co-ops in the housing plan amount to less than two percent of the total $78.5 billion.

In my view, the philosophy of our National Housing Strategy seems largely based on a misdiagnosis of the problem that leads to a simplistic assumption that merely increasing the supply of housing, of whatever variety, will solve our problems. We see the same thinking winning the day in British Columbia. Unfortunately, scarce as hens’ teeth is the evidence that simply adding a substantial number of rental units nationwide will reduce and hopefully reverse the recent increases in market rental rates.

Canada’s auditor general has provided us with a sharp lesson by demanding we tie any subsidies or incentives for constructing new housing to demonstrable proof that the kind created will directly benefit those hardest hit by housing unaffordability.

***

This story originally appeared at The Tyee on January 5, 2023.

**