Guest Contributor: Robert Renger

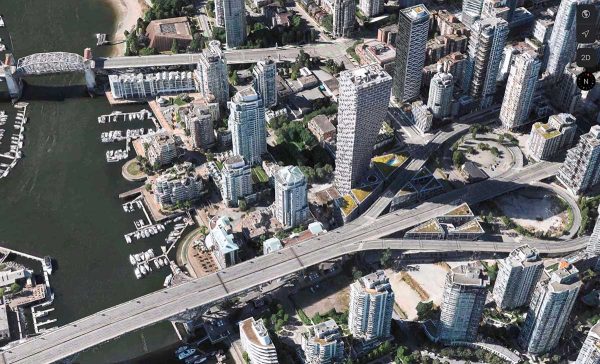

Ten years ago the City of Vancouver sold developer Westbank about 87 percent of the site for “Vancouver House” for $32 million — about $96 million below market value. Rezoning was already in place to allow taller, denser development.

The public land, about 1.1 hectares, was superbly located at the north end of the Granville Street Bridge, steps from beaches.

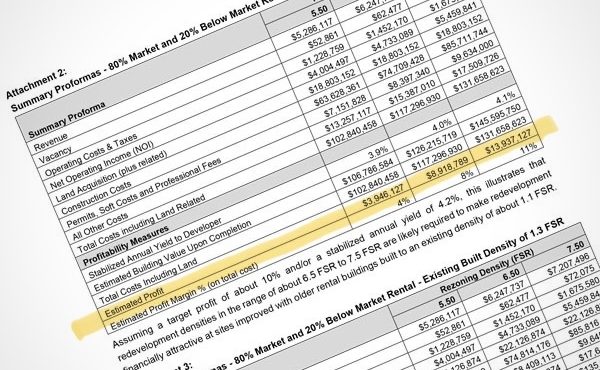

In Vancouver and across B.C., developers offer Community Amenity Contributions in return for rezoning that increases land value.

The contribution from Westbank was surprisingly low for a development of this size, especially in light of the $96-million increase in land value provided by the 2014 rezoning for the property.

The Community Amenity Contribution negotiated by city staff was $4 million cash and $6 million in-kind “public realm improvements.” The city’s stated policy is to negotiate for CACs equal to at least 75 percent of the increase through rezoning. In this case, city staff settled for 10 percent, with only four percent in cash.

The developer published beautiful renderings of the planned urban realm below the bridge.

The architect firm Dialog produced an info sheet titled “Catalyzing untapped urban spaces under the bridge,” writing of “a mixed-use urban village under the bridge” and that “a central cathedral-like urban realm below the bridge offers ample opportunity for a variety of uses and public events.”

At the Urban Design Panel in April 2012, architect Bjarke Ingels spoke of the opportunity to create a desirable neighbourhood under the bridge, where the covered area could be exciting for different events from a beer garden to weekend markets.

He said lighting under the bridge could enliven the area and in the evening restaurants could spill out into the space. There could be a permanent climbing wall or there could be an art installation. Ingels added there were lots of opportunities to make the area exciting and useable.

Public realm elements mentioned in the city planning department’s 2013 rezoning report and at the public hearing, included:

- High-quality surface treatments, special lighting, kiosks, and public seating;

- Street trees and landscaping for Granville Street under the bridge, and for the newly created adjoining streets;

- Upgrading the south side of Pacific Street with a separated bike lane, street trees, and landscaping;

- Pedestrian-level lighting on the streets;

- Direct and enhanced pedestrian connection (elevators/stairs and horizontal bridge) between the upper Granville Bridge deck and Granville Street below;

- Pedestrian access through the terraced semi-public courtyards to Pacific Street; and

- Provision of infrastructure, to support public realm programming… including electricity, water, storage and accessibility to public washrooms.

To overcome the difficulty of using the sloped area under the Granville Bridge for special events, the developer’s submission said that “leveled outdoor rooms” would be created, connected by steeper vehicle ramps and pedestrian steps.

But after the Vancouver House development — 52 storeys, with condos costing up to $12 million — was completed, people complained the public realm under the bridge was not as beautiful as the developer’s renderings.

Indeed, many of the promised elements are missing.

There are no street trees, no landscaping, and no pedestrian-level lighting on Granville, Continental, and Rolston streets under the bridge and ramps. The pre-existing slope of the area under the Granville Bridge has remained, with no sign of the “leveled outdoor rooms” that had been designed to accommodate special events.

Both the public access stairs leading up from Pacific Street to the “semi-public courtyards” are blocked by locked doors. Security staff said that the stairs and courtyards are private property with no public access. They also said that the public elevators up to the bridge sidewalks have been out of service for at least six months. There are no public washrooms, but security said to use the ones in a nearby food store.

Pacific Street has been upgraded beside the development site, but it seems strange to have credited this as a Community Amenity Contribution since it was just a normal servicing requirement.

In order to properly understand what the public had received for the $6-million Community Amenity Contribution, I made a freedom of information request in June for an “itemized list with cost estimates of the public realm improvements comprising the $6 million in-kind Community Amenity Contribution….”

I clarified that I wanted whatever records the $6-million in-kind contribution figure in the city planning department’s 2013 report was based on.

The city’s Access to Information and Privacy Office responded. “Our office has received confirmation from the necessary staff with regards to your request, and have been informed that there is no pre-existing list of the Public Realm Improvements referenced in your request.”

That was astonishing.

Where did the $6-million valuation of Westbank’s promised amenity come from?

How did the city and developer know what was required to meet the rezoning requirement?

How could the city ascertain whether or not the in-kind Community Amenity Contribution had been completed?

A $6 million in-kind Community Amenity Contribution, accepted instead of a cash CAC, should be regarded as a $6 million expenditure by the City, and should be managed with a corresponding degree of care.

The in-kind Community Amenity Contribution could have been (but was obviously not) managed similarly to an Engineering Department Services Agreement, with:

- A schedule of required works with cost estimates;

- Descriptions, drawings, and specifications;

- A security deposit to ensure the work is completed; and

- Inspection by city staff before the deposit is released.

Without even a list of the public space improvements to be provided, it is hard to imagine how city staff thought they would be able to manage this $6-million in-kind Community Amenity Contribution.

City staff’s job is to protect the public interest by ensuring developers deliver on the promised commitments.

They didn’t do so very effectively, judging from the results.

PS: About that chandelier

The famous $4.8-million chandelier artwork under the Granville Bridge, which has been both celebrated and derided, was not part of Westbank’s $6-million in-kind public realm Community Amenity Contribution. Westbank provided it to meet the city’s requirement for public art priced at $1.81 per square foot for buildings larger than 100,000 square feet. Because that only worked out to $1.3 million for the 700,000-square-foot Vancouver House development, the city allowed Westbank to add in its public art obligation for three other developments — the Butterfly at Nelson and Burrard, the 400 West Georgia office tower and a project at Joyce-Collingwood Station.

Why a chandelier under the bridge? Perhaps it is a response to Anatole France’s observation that “the law, in its majestic equality, forbids the rich as well as the poor to sleep under bridges.” The chandelier’s message is a more positive one about equality — that people passing by, people sleeping under the bridge and people in Westbank’s luxury development can all enjoy the opulence of fine public art.

***

This piece was originally published on the Tyee.

**

Robert Renger was the senior development planner for the City of Burnaby and the city’s lead for the planning and development of the UniverCity community at Simon Fraser University.