Jordi Honey-Roses, Silvia Casorran Martos, and Xavier Matilla, warmly greeted the British Columbian planners as we approached the intersection of Carrer de Roc Boronet and Carrer de Sancho Avila—ground zero of the first Superilla experiment.

As mentioned in Part 9, the pioneering urban planning project focused on making the city more livable, sustainable, and community-centered—addressing modern environmental and social challenges.

While earlier mobility plans laid the groundwork, the concept was included in the 2013-2018 Urban Mobility Plan (PMU). However, it was under the Colau administration that the first pilot project was launched in El Poblenou. The city sought to reduce car dependency and prioritize sustainable transport like walking, cycling, and public transit, while expanding limited public and green spaces in the densely populated city.

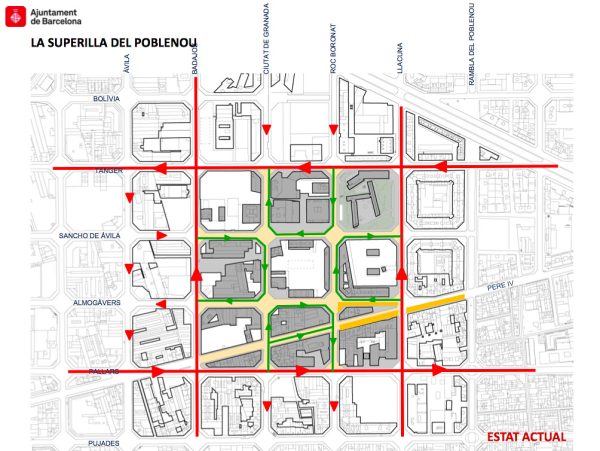

The core concept reorganizes parts of the city into “superblocks,” clusters of nine city blocks that restrict car traffic to accommodate pedestrians, cyclists, and green spaces. Interior streets are closed to through traffic but remain accessible to residents, emergency services, and deliveries. The aim: to reduce noise, pollution, and accidents while creating more public spaces for walking, playing, and socializing.

The first experimental Superilla was in El Poblenou—where we now stood—a neighborhood undergoing transformation as the 22@ Innovation District with a mix of residential and industrial spaces. The intersection where we sat offered the ideal setting for our hosts to explain the key elements of the pilot: streets closed to through traffic and converted into green areas, pedestrian paths, and public seating.

This transformation followed a tactical urbanism approach—low-cost, small-scale interventions that tested new ideas and encouraged community involvement. This allowed the city to experiment with innovative solutions before making long-term investments, allowing flexibility and adaptability.

Key elements of this transformation included:

- Restricted traffic access for residents and essential vehicles only.

- Expanded sidewalks and pedestrian zones.

- New green spaces for gathering and socializing

- Dedicated cycling paths, for safer, non-motorized transport safer.

In keeping with an evidence-based approach, the City and Honey-Roses gathered and analyzed data immediately after its implementation to assess effectiveness. It wasn’t perfect—conflicts between pedestrians and vehicles arose, However, perfection wasn’t the goal—learning was.

Despite initial imperfections, the Poblenou experiment quickly showed clear benefits: reduced air and noise pollution, fewer accidents, and increased public space usage by the local community. These were in line with Barcelona’s goals.

It needed to evolve.

Remarkably, the next iteration didn’t take place in the same area. Though the transformations in Poblenou were “unrefined,” the community’s attachment to them was so strong that they largely remain to this day. Some areas, like Carrer dels Almogàvers, continue to be improved as a new pedestrian axis, and new public spaces, such as Plaça Isabel Vilà, have emerged.

The next Superilla experiment was set in a higher-profile location: around the iconic Sant Antoni market designed by Antoni Rovira i Trias in 1882, at the other end of the Eixample. Here, the Superilla concept transformed into something even more ambitious—moving to its second three stages.

We hopped on our bikes…

***

Other pieces in the Barcelona Chronicles:

- Part 1 – Introduction

- Part 2 – Cerdà and Colau: Two Key Figures

- Part 3 – The Barcelona Housing Policy 2015-2023 Overview

- Part 4 – Defining Affordable & Social Housing

- Part 5 – Supplying Affordable Housing

- Part 6 – The 30% Measure and Others

- Part 7 – Vancouver v. Barcelona – Foundations

- Part 8 – Barcelona v. Vancouver – Strategies

- Part 9 – The Eixample and the Superilla

- Part 11 – The Superilla…Evolved

- Part 12 – Vancouver v. Barcelona – Urban Design

- Part 13 – Reflections on Two Cities

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.