Cities host our lived experiences. They are more than mere words in reports or policy documents; they are tangible environments that shape our daily lives. These urban spaces consist of physical materials molded into structures and places that influence how we move, connect, and think.

Yet, it’s easy to lose sight of this reality, especially when cities are viewed as abstractions—defined by terms like “economies,” and “social networks,” rather than as physical entities with concrete impacts.

City planning suffers from a disconnection between policy and physical reality. Politicians, municipal workers, and decision-makers frequently focus on metrics like unit counts, floor space ratios, and density figures without considering the real-world implications for communities.

This tendency to reduce cities to numbers, graphs, and other abstractions can result in sweeping changes that ignore the day-to-day experiences of residents and are detrimental to how the city works and feels on the ground.

In contrast to abstract planning, Barcelona’s Superilla initiative demonstrates a more grounded approach to urban transformation. The Superilla, a neighborhood-level project, reimagined public space by prioritizing pedestrians and cyclists over cars. While initial policies set targets, the real impact was seen in the physical changes experienced by residents. Within a decade, the initiative had transformed the city in meaningful ways.

The Superilla‘s success was rooted in a clear strategy:

- Prioritize all citizens by ensuring that public space serves the community.

- Set cross-disciplinary targets to address social, environmental, and economic goals.

- Launch small, viable pilot projects that could be tested and refined.

- Use evidence collection and analysis to inform decisions and adjust strategies.

- Scale successful interventions incrementally while discarding ineffective models.

- Empower local decision-making to keep citizens engaged and involved.

This approach allowed the city to evolve naturally, adapting to changing circumstances while avoiding the risks associated with drastic, large-scale reforms.

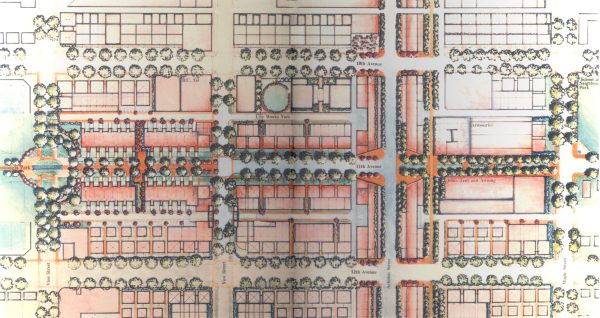

The importance of incremental, evidence-based planning is not a new idea. It goes back to the earliest settlements and is found in Cerdà’s Eixample design in Barcelona, despite being a large-scale masterplan. As discussed in previous pieces in the Barcelona Chronicles, the 19th-century urban plan was based on rigorous analysis, including demographic studies, building assessments, and environmental factors such as sun and wind patterns. Cerdà’s plan laid a flexible framework for gradual implementation and ongoing refinements over decades.

However, even Cerdà’s method had its flaws. As we’ve seen, the Superilla addressed the system-wide problems that developed from the initial plan.

More recently, the failures of Modernist architecture and urban planning in the mid-20th century serve as a cautionary tale. These large-scale projects often imposed untested models on cities, leading to outcomes that will negatively impact urban life for generations to come.

The lesson is clear: large-scale planning can succeed only with a solid foundation of data, flexibility to adapt, and meaningful citizen feedback.

In Vancouver, recent initiatives like the Broadway Plan and Transit-Oriented Area regulations ignored these principles, failing to prioritize neighborhoods and their residents.

They involve broad, large-scale transformations that have not been sufficiently tested through evidence-based methods. Their reforms aim to radically reshape thousands of hectares of land and existing communities but overlook critical factors, including infrastructure impacts, park space provisions, and the specific needs of neighbourhoods, to name a few.

The city’s Social Housing Initiative and Vancouver Plan also overlook these essential considerations, favouring developers’ interests over citizens’ quality of life.

The demolition of community-oriented urban fabric is planned without proper assessment of those who will be affected or what is and isn’t working in these areas.

This is a recipe for disaster.

The risks associated with these untested policies are significant; if they fail, the consequences will be severe and difficult to reverse. Longstanding, more affordable, housing in older buildings once lost can never be recaptured. This is why incremental approaches are preferred.

On a smaller scale, Vancouver’s parklet program exemplifies the value of community-focused, incremental urban design, but it also has many shortcomings in comparison to Barcelona’s counterparts.

The initiative began as a pilot project from 2011 to 2013, replacing parking spaces with public areas where people could gather and socialize. The city officially adopted the program in 2016, and parklets can now be found across Vancouver, maintained in partnership with local businesses and organizations.

Despite their popularity, the parklet program remains limited in scope. The interventions are still considered “temporary,” with little discussion about expanding the program or integrating it into a broader urban planning strategy for the city. Roughly half remain in downtown Vancouver, with few other neighbourhoods receiving the benefit.

This reflects a larger pattern in the city’s urban design efforts, where successful initiatives are left in a state of stagnation rather than evolving into permanent solutions.

Other recent projects, like separated bike lanes and community public plazas, share similar challenges. While they offer benefits, they lack a systematic approach that could help scale them up across the city and create a cohesive, long-term vision.

An example of a more ambitious urban transformation is Vancouver’s Arbutus Walk, a mixed-use development that replaced a former industrial site over two decades ago. The project prioritized pedestrians and cyclists with a central greenway and converting existing roads into public spaces.

Community involvement played a significant role in shaping the project, leading to the choice of mid-rise housing over high-rise towers, which allowed for more sunlight, open spaces, and a diverse demographic mix.

Completed in the early 2000s, Arbutus Walk is considered a success in creating a livable, integrated urban neighbourhood. A brief walk in the area is enough to see its benefits.

However, like the parklet program, it remains an isolated case. The city did not collect comprehensive data or analyze its broader impacts, missing an opportunity to use this model as a foundation for larger, city-wide transformations despite making a strong case for transforming redundant street infrastructure into public amenities.

The absence of follow-up investment or planning leaves Arbutus Walk as a standalone project rather than a catalyst for broader change.

The 2010 Olympic Village met a similar fate. Built on a former industrial site, the Village became a vibrant, mixed-use, sustainable community incorporating best practices of the time.

It features eco-friendly mid-rise buildings, diverse housing options, and integrated public spaces, with a design that emphasizes green technologies, including energy-efficient systems, renewable materials, and water conservation.

The layout encourages walkability, public transit access, and a balance between residential, recreational, and commercial spaces, setting a new standard for sustainable urban living in North America.

Physically, it created beautiful spaces that all citizens continue to enjoy.

Despite its innovations and appeal, the Olympic Village too remained an isolated effort. Soon after completion, the city reverted to market-driven, short-sighted planning approaches.

Notably, in the fall of 2010, Vancouver’s Olympic Village was named the “most liveable community in the world” by LivCom, a UK non-profit advocacy initiative in collaboration with the United Nations, beating out projects submitted by over 20 countries. Vancouver City Council, who campaigned against the project, declined to celebrate the award publically.

The shortcomings of Vancouver’s smaller-scale projects and failing large-scale initiatives highlight the need for a systematic urban design process.

Barcelona’s Superilla exemplifies a strong, simple method. One that dates back to the earliest cities, showing that cities can evolve to benefit all residents when changes are made incrementally and based on evidence.

Vancouver, by contrast, often stalls at the pilot stage or does not adhere to the time-tested strategies seen in Barcelona.

It is important to recognize the fundamental difference between writing abstract policies and managing physical change over time. Physical transformations require that planners and decision-makers adopt strategies that allow for adaptation and scaling up. This means starting with small interventions, collecting data, and refining the approach over time before rolling out changes at a larger scale.

A city-wide vision must integrate individual projects into a cohesive framework that prioritizes citizens’ needs and responds to the urban environment’s complexity.

As cities face urgent challenges like climate change and growing populations, it is essential to move beyond the temporary measures and fragmented initiatives we see in Vancouver. The lessons from the Superilla demonstrate how gradual, evidence-driven, and community-focused urban design can transform cities meaningfully.

In Vancouver, it’s the “market”—shaped by elected officials and industry influence—that drives the city’s values, priorities, and planning strategies.

We need to shift focus to city-making that fosters social exchange and builds valuable social capital. This means creating local experiences that strengthen community trust and build capacity in meaningful ways.

The time has come for us to commit to long-term strategies that scale up successful projects and create an inclusive, resilient future for current and future residents. This means radically reforming the narrow investment-driven, myopic, and regressive plans we have seen grow recently.

We must prioritize incremental changes based on real-world outcomes, and avoid repeating mistakes of the past: embracing a planning approach that serves everyone.

The opportunity to reshape urban life is within reach, but it requires a shift away from short-term solutions toward a systematic vision that connects every intervention to a larger purpose.

***

Other pieces in the Barcelona Chronicles:

- Part 1 – Introduction

- Part 2 – Cerdà and Colau: Two Key Figures

- Part 3 – The Barcelona Housing Policy 2015-2023 Overview

- Part 4 – Defining Affordable & Social Housing

- Part 5 – Supplying Affordable Housing

- Part 6 – The 30% Measure and Others

- Part 7 – Vancouver v. Barcelona – Foundations

- Part 8 – Barcelona v. Vancouver – Strategies

- Part 9 – The Eixample and the Superilla

- Part 10 – The Superilla Pilot

- Part 11 – The Superilla…Evolved

- Part 13 – Reflections on Two Cities

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.

One comment

Another well thought out critique from one of our region’s more progressive and persuasive urban analysts. Poignant and informative