It seems to us that this connection—or better perhaps, confusion—between care and domination is utterly critical to the larger question of how we lost the ability freely to recreate ourselves by recreating our relations to one another. It is critical, that is, to understanding how we got stuck, and why these days we can hardly envisage our own past or future as anything other than a transition from smaller to larger cages.

David Graeber and David Wengrow, The Dawn of Everything.

In The Dawn of Everything, Graeber and Wengrow challenge us to rethink humanity’s story as more than a one-way march toward hierarchy and centralized authority. They remind us that human history is a tapestry of choices, where societies chose to cooperate or control. Power and care have always coexisted, the balance we strike between them shapes how communities nurture or oppress their people.

Through countless examples, Graeber and Wengrow show how societies have organized themselves around cooperation and mutual aid, illustrating that control and care often coexist in varying proportions. These dynamics influence how communities protect, nurture, and govern themselves.

This tension between care and domination surfaces starkly in modern urban planning, where decisions made in the name of “care” frequently mask harmful intentions. At the core of this harm is zoning—a tool originally designed to “serve the public good” but now often functioning as a means of exclusion, demolition, and segregation.

Zoning’s origins lie in early efforts to separate residential, commercial, and industrial areas to improve public health and environmental safety. Over time, however, zoning morphed into a tool to divide communities along racial and economic lines. Under the guise of “improvement,” it has been used to demolish long-established neighborhoods and displace vulnerable communities, creating barriers rather than bridges.

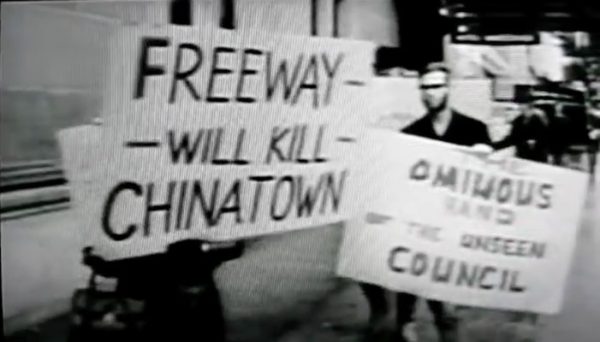

Metro Vancouver is just one of many cities scarred by the meat ax of harmful zoning practices. The construction of the Georgia Viaduct erased Hogan’s Alley, a once-thriving Black neighborhood, under the pretext of urban renewal. In West Vancouver, zoning laws once barred people of African or Asian descent from living there unless employed as domestic workers. These policies—framed as progress—left deep wounds on the city’s social fabric.

Mid-20th-century urban renewal programs carried a brutal legacy. Entire communities were uprooted and displaced under promises of revitalization. Families lost homes. Social networks were shattered. Thriving neighborhoods were replaced by highways and sterile developments. Instead of renewal, these actions created cycles of instability and displacement that haunt cities to this day.

Although many believe these episodes to as blips in the steady progress of urban planning towards more just ends, Graeber and Wengrow remind us that the myth of care persists. We continue to see the same insidious language plaguing our City Halls, supporting initiatives of violence and destruction.

Today, affordable housing projects supported by “pro-development” groups often carry a language of compassion but conceal violent impacts. In a pattern thousands of years old. What is framed as care—providing much-needed housing for those in need—slips into the opposite.

New developments that claim to provide affordable options frequently come hand-in-hand with displacing existing residents and pricing out the very people they are supposed to support. These projects may satisfy a checklist of affordable housing requirements and “unit counts,” but they often fail to account for the deep-rooted needs of the communities they disrupt.

The actions of former Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti and California State Sen. Scott Wiener are emblematic of this broader North American trend. In partnership with the real estate industry and Yes-In-My-Backyard (YIMBY) groups—they pushed deregulation, market-driven housing policies, and destructive “trickle-down” narratives, under the guise of solving the housing crisis.

As Patrick McDonald details in Selling Off California, this opened the door to squeeze as much profit as possible out of California renters, sacrificing protections for middle- and working-class residents, and contributing to soaring rents, mass gentrification, and displacement. Their promise that market developments would eventually reduce rents across the market proved disastrous.

Does any of this sound familiar?

It should.

The same “trickle-down” and market-driven narratives come out of the mouths of many locals—from Council members to the seemingly innocent propagandists like Uytae Lee—who conveniently omit or gloss over examples that clearly show the harms done by these same arguments.

As such, McDonald’s story is not just about California. It is a cautionary tale for all cities that tout the same market-based solutions to solve affordability issues. It becomes even more problematic within the context of the environmental impacts of these massive rebuilding efforts.

Simply put: zoning, wielded thoughtlessly or with profit-oriented motives, becomes a force of structural violence rather than one of care, protection, or empowerment. It turns the intent to help into a mechanism for harm—of humans and non-humans, alike—amplifying inequality under the guise of “protection” and “love.”

We must displace you, destroy your neighbourhoods, shatter ecological systems, and devastate social bonds because we care about you.

This is the message. Violence and care are entangled. Confused. Violence is planning. Planning is violence.

In Vancouver and across cities in North America, today’s planning conversations ring with the same hollow promises. The Province’s Transit-Oriented Planning mandates, Vancouver’s Broadway Plan, and countless other similar initiatives tout ideas of care, promising improved housing and transit access. Yet these initiatives are leading to displaced communities under the guise of renewal.

Vanessa Machado de Oliveira’s call to “hospice modernity”—to confront the harmful systems and mindsets underpinning destructive practices like these—reminds us that the colonialism, capitalism, and anthropocentrism that feed our top-down systems of planning have devastating consequences and need to be guided to a dignified end of life

Graeber and Wengrow describe how, in the past, people faced with violent systems often chose exodus, moving to neighbouring communities that embraced different, more egalitarian ways of life—a process called “schismogenesis.” Yet today, as we live within a global capitalist system, there is often no escape. The dominant model of top-down, profit-oriented planning creates a trap, leaving people “stuck” and overwhelmed by forces outside their control.

Alternatives, however, are still possible. Rather than rigid zoning that seeks to overrule the public, we could embrace more flexible, mixed-use neighborhoods that support social and economic diversity. Community land trusts and collectively owned land, done right, can offer solutions that keep residents rooted while incorporating new development.

Planners could look to create community resilience by investing in social infrastructure—parks, libraries, and community centers that connect and empower neighborhoods. These elements, conspicuously absent from Provincial and local transit-oriented plans, are fundamental for creating neighborhoods where people feel a true sense of belonging.

Social infrastructure is more than a list of amenities. Research shows that communities with strong social bonds experience lower crime rates, as residents share a sense of responsibility and mutual care. By fostering social cohesion, communities can face challenges together, solving problems without relying on external controls. When residents feel invested in their neighbourhoods, the need for coercive planning interventions diminishes.

In terms of housing, we must consider alternatives to mass destruction and construction. As architect Jeanne Gang highlights, we face an urgent need to do “much more while using less.” She rightfully asks: “When you need to build, what should be done when the best answer might not be to build at all?”

Building simply for the sake of building is no longer sustainable. Gang recommends prioritizing the “art of architectural grafting”—maintaining healthy building fabric wherever possible and integrating affordable housing into thriving communities without uprooting them. Planning must support transformation in ways that respect the working urban fabric and existing social structures, rather than violently replacing them under the guise of “affordable housing”. Environmentally, we have no other choice.

Graeber and Wengrow’s insights teach us that societies organized around shared decision-making tend to foster more ‘egalitarian’ communities. Their thoughts on community autonomy echo the potential need for more participatory urban planning. Allowing residents to participate directly in shaping their neighbourhoods through methods like participatory budgeting and community-led design fosters agency, ownership and gives communities a real voice. This offers an antidote to the increasingly authoritarian style of planning that has become common, as “care” is used to sideline true community input.

When people feel they have a hand in shaping their surroundings, they are more likely to work toward shared goals. Instead of seeing urban planning as a way to “manage” populations—and providing affordable housing as simply counting units—we must approach it as a tool for empowering resilience, equity, and connection. Achieving this requires an honest look at how zoning and redevelopment have perpetuated violence in the past and continue to do so.

We must decouple violence from planning to build cities that help people thrive.

We must shift practices to prioritize stability and equity over financial gain, particularly zoning. True care in urban planning centers on the human and ecological well-being of communities, respecting the needs of both current and future residents. By aligning planning with values of cooperation, adaptability, and solidarity, we can begin to move from a model of domination to one of genuine care.

Only then can cities become places where people feel truly at home, where safety, belonging, and hope are woven into the urban landscape. Planning should not be an act of control but a commitment to nurture, foster, and respect the communities it touches.

***

Addendum

I was listening to the video of the City of Vancouver’s November 14th public hearing while putting the final touches on When Care Becomes Control. Just before voting against strong and reasoned community arguments, Councillor Brian Montague offered the following statement:

I just wanted to say that a lot of speakers came out the other night but just to remind everyone that these are quasi-judicial hearings. This is where Council has to put on their land regulator hats and make decisions that are based on certain criteria, and what is in the best interest of the city, and not necessarily on emotion. You know, we have to judge the merit of the project, does it align with City policies. You know, the fact that the City’s been in a 40-year drought on purpose-built rental, density around transit, all these sorts of things…the fact that the City has a less than 1% vacancy rate. So, I just wanted to remind all the speakers and let them know that there’s a lot of things that go into the decision of Council.

Councillor Montague’s remarks exemplify the message of When Care Becomes Control. His troubling dismissal of community voices as “emotional” reflects a broader, historically entrenched pattern of those in power devaluing the lived experiences of the people they claim to represent—again, under the guise of care. This framing perpetuates a false dichotomy between emotion and rational decision-making, ignoring the essential role emotional intelligence plays in ethical governance.

Labeling community concerns as mere “emotion” reflects a failure to recognize that emotions are not in opposition to rationality—they are often deeply rooted in lived realities, historical injustices, and the tangible impacts of policy decisions. To dismiss them as irrelevant is to undermine the democratic process and erode public trust in leadership.

Furthermore, framing the public hearing as a “quasi-judicial” process is problematic and dangerous when used to stifle community input. While technical criteria and policy alignment are essential, they must not overshadow the voices of those directly affected.

Councillor Montague failed to cite any specific criteria in his justification, demonstrating a lack of understanding that policies themselves are not neutral; they are shaped by values and priorities. By dismissing public testimony, he effectively elevated bureaucratic expediency over justice.

The Councillor’s reference to the 40-year “drought” on purpose-built rental housing and a less than 1% vacancy rate underscores the gravity of Vancouver’s housing crisis. Yet, dismissing residents’ perspectives as mere “emotion” undermines potential solutions. This crisis cannot be resolved by undermining the perspectives of citizens.

It is precisely the community’s “emotional” testimony that often sheds light on the unintended consequences of top-down planning decisions—consequences that data alone cannot fully capture.

History is rife with cautionary tales of leaders who prioritized technocratic solutions over community voices, resulting in destructive urban policies. From the displacements of mid-20th century urban renewal to modern struggles with gentrification, many examples illustrate the perils of sidelining lived experience in favor of technocratic efficiency.

If Council truly aims to serve the city’s “best interests,” it must embrace emotional intelligence and recognize community feedback as a vital compass for equitable decision-making. Far from being a nuisance, public testimony offers a lens into the real-world consequences of policy choices.

In the spirit of adhering to specific criteria, Councillor Montague’s statement falls short of the Oath of Office principles he swore to uphold, specifically the commitments to “respect others” and demonstrate “leadership and collaboration.” This disregard for community voices highlights a deficit in both integrity and accountability to the people he was elected to serve.

Equally troubling is the apparent consensus among his colleagues, as none expressed any surprise at his remarks, suggesting this sentiment is widely shared.

True leadership demands humility, empathy, and a willingness to learn from the wisdom embedded in community voices. Anything less is not governance; it is paternalism disguised as professionalism.

***

Related Spacing Vancouver pieces:

- Trifecta of Control

- Entitled to Flip

- When Care Becomes Control

- The Slow Emergency

- The Broadway Plan Blues

- Learning from Moses

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.

8 comments

It’s tragic that the council is overlooking the perspectives of wealthy west-side residents. Sure, we just had an election where the NDP won with promises to build more housing near transit, but what they fail to realize is that the voices of those who voted for them don’t matter. These voters lack the unique community insight that comes from owning a multi-million dollar property on the west side. Democracy, it seems, can backfire — especially when it means long-time homeowners and elite residents of Arbutus Ridge could be outnumbered by renters hoping to move into the neighborhood. We can’t let that happen.

Dear Mr. McRae,

Thank you for the inadvertently supportive comment. According to Graeber and Wengrow, your words are a strong example of the false narrative of care promoted by your governing authority.

According to their work, the “elites” you seem to be critiquing are a function of the system created by centralized authorities. In the contemporary world, this includes but is not limited to Vancouver City Council and the NDP whose actions you seem to be supporting.

A quick read of the news, for example, quickly shows that renters are among those most opposed to many of these top-down initiatives that cut across areas well beyond the Arbutus Ridge. Opposition rallies by tenants and renters have already taken place at City Hall and other locations. But the message of these communities continues to be subdued by false narratives of care—ones that state above that foster societal division and fragmentation.

This not to undermine the need for housing. This fact is obvious…and in contrast to the standard narratives we hear, most, if not all people, in Metro Vancouver do not argue this. What’s critical is HOW to provide it.

In line with Graeber and Wengrow’s argument, societal organizations based on hierarchy and domination foster the growth of systems that neutralize or destroy more ‘egalitarian’ systems in favour of ones that amplify hierarchy. Believing otherwise is an illusion. This is supported by countless other people in different disciplines, including Thomas Picketty’s research published in his wonderfully exhaustive tome Capital in the 21st Century.

If this centuries-old pattern is true, then any of the solutions touted by our current governments based on domination and centralized authority—especially ones that neutralize community input—will ultimately SERVE the ‘elite,’ not the opposite. Therein lies the sad irony: it is through believing and (re)stating false narratives of care that citizens within these societies of domination promote the system that works against them.

The inherent contradiction of your argument points to the importance of Graeber and Wengrow’s work. They offer alternatives that are much different than anything we see in the current world. Ones that have taken past societies much closer to the ‘egalitarian’ than could imagine. Along the way, they bust the myth that cities must be hierarchical and have centralized authorities. According to their research, this is simply not true. This helps reframe the role of—or need for–centralized authorities to ‘speak for’ the citizens.

I suggest carefully reading and analysing Graeber and Wengrow’s book. If not, you run the risk of inadvertently harming the very people that you seem intent on supporting. Conversely, if your goal is to intentionally harm this people…keep up the good work.

Best of luck,

E

P.S. An important note on “democracy.” From what I understand, the Greek definition of “democracy” (that I assume you are referring to) was based on a lottery system of governance. Those early thinkers would say we do not live in a ‘democracy’ at all, so its backfire is inevitable. The Dawn of Everything speaks to the issue of ‘equality’ and ‘egalitarian’ in a more meaningful, and useful way than using these vague Eurocentric terms that have been abused to the point of irrelevance. More reason to read to book.

Sure, our Westminster-style democracy and representative council system have been in place for hundreds of years, enduring world wars, the Great Depression, and other crises. Yet clearly, it cannot adapt to the current world. Allowing an apartment building to be built in a detached housing zone is simply too complex a decision to be handled by our representatives and the voters who elected them. Some misguided voters, especially renters, might think, “Hey, these are single-family homes, so we should definitely replace them with larger apartment buildings to make it easier to find a place to rent.” But those people fail to appreciate the ancient wisdom that comes with owning a detached home. Maybe you’re right that democracy is too Eurocentric. Still, I think the ancient Greek system of allowing only property owners to vote might bring about the outcome you’re seeking: no more rental towers.

Dear Mr. McRae,

Thank you again, for your inadvertently supportive comments!

Unfortunately, there are so many factual errors in your statement that any attempt at meaningful dialogue would be wasteful, and we would only achieve damaging to your good name. I suggest reading up about the “representative council system” and Greek systems you mention to become more informed. In the spirit of enticing you hit the books, however…some tidbits of information.

The “Westminster model” you mention was very different than our own. Property rights as we know them today, were not a part of that system. Arguably, came much later in the 1800s in the UK when governments actively, and systematically enclosed “common” land in the name of industrialization efficiencies—against the will of the people, I should add. Do you know the system it replaced? Most don’t since it isn’t the subject of standard history books. Your statement assumes that there were no other systems at the time.

More problematic, you assume that because that system has some (small) semblance to what we have now, it was the better system. A dangerous assumption that Graeber and Wengrow absolutely annihilate, as it devalues the richness of other societal traditions. Again, all you are doing it proving my point, so thank you.

Also, “Ancient Greeks” never understood “property” in contemporary sense, since they did not have a “property system” at all. Common scholarship attributes the origins of the modern definition of “property” to the Romans (dominium), well after the decline the Greek “Golden Age”. But that radically changed over time, as well. Moreover, the Greek landscape was also littered with slightly different governance systems. So, if one wanted to get very technical there is actually no standard “Greek system” at all.

It’s worth also mentioning that Westminster, “Greek” and “Roman” societies you refer were all centralized authorities. So, you seem to be expressing support for authoritarian and centralized governments. And again, if that is intentional…sure, all the power to you. Admittedly, I don’t share your enthusiasm given my view of history—leaning more towards more truly people-based governance.

As suggested, reading “The Dawn of Everything” might help you with some of your arguments. At the very least, it might open your eyes to some of the hidden biases we have about governance structures and where they come from.

Anyhow, it’s been fun….but again, I have neither the need nor desire to banter virtually with yet another person who goes through the hamster wheel of common, predictable, and false myths. I have enough of that in my in-person life and at the very least I get to see these people with my own two eyes.

Best of luck!

E

Alexander McRae is completely missing the context of the councillor’s comment. It wasn’t wealthy westside residents. It was in east vancouver. Residents were united in their opposition to a rezoning application that would plunk a 19 storey tower on a small residential street, completely out of scale with the surrounding streetscape. It’s easy to sweep the concerns of neighbours under the rug and argue about notions of democracy, however, many of us walked away from the council meetings of the week feeling like the democratic process in this city is a farce after watching the unanimous approval by council of this project.

It’s easy to call democracy a farce when things don’t go your way. You can stamp your feet and complain, but both the recent BC and Vancouver elections show that anti-housing positions are increasingly unpopular among the city’s electorate. Maybe consider why so many people have turned against complaints about “scale” and other issues when so few in our region have the opportunity to rent in Vancouver’s core neighborhoods. Of course, homeowners complain—they’ve got theirs, so who cares about everyone else? But the have-nots have steadily outnumbered the haves in this city, making their position politically untenable for anyone trying to win a majority government. It seems your issue with democracy is actually with the voters and the public. This is why calls for some kind of hyper-local autocracy seem appealing to people like Erick.

Dear Mr. McRae,

It’s easy to dismiss critiques of housing policy as sour grapes while oversimplifying both the electoral landscape and the issues at hand, as you have. Congratulations, all you have proven here is your limited knowledge of both local and global history, a skewed (arguably racist) understanding of political systems, an inability to read thoroughly (“anti-housing” was not stated once, in fact I explicity stated housing was necessary), and now we can add minimal empathy towards anyone different than yourself.

Unfortunate, to be sure.

Demonizing others is truly a bad look. I warned you earlier to stop while you were ahead. All communication is self-disclosure.

I kindly ask that you refrain from any other comments. This platform is intended for meaningful dialogue and debate.

The only comment in this thread that makes sense is Local Resident.