“We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.” — Albert Einstein

Across cities like Vancouver and beyond, the glass-and-steel high-rise has become a symbol of progress—dense, efficient, and seemingly inevitable. Urban planners and developers champion these towering structures as solutions to population growth, land scarcity, and housing affordability, while economic models and real estate analysts reinforce these claims with data.

Yet, as our skylines stretch ever higher, the shortcomings of the high-rise model—at least as it is currently practiced—are becoming increasingly difficult to ignore. The environmental, social, and economic costs of these developments, often omitted from standard calculations, demand serious reconsideration. In an era of climate instability, environmental fragility, and deepening social inequities, we must ask: Are we building for the future, or repeating the mistakes of the past?

At its core, a high-rise is a simple exercise in stacking space—something any child with a set of Lego bricks understands intuitively. Architectural history offers countless variations on this theme, with structures that respond to their environments, available technologies, and cultural values. High-rises are no exception; they are shaped by the priorities of the societies that build them. And while tall structures have existed for centuries, their widespread use as primary residences is a relatively new experiment—one that remains largely untested over the long term.

Despite a rich history of architectural innovation, most contemporary high-rises follow a rigid formula dictated by economic efficiency rather than human well-being. While visionary exceptions exist, they remain anomalies—not necessarily because they are flawed, but because they do not align with the financial and regulatory structures that shape modern development. As a result, many residential high-rises fall short when viewed through a broader lens.

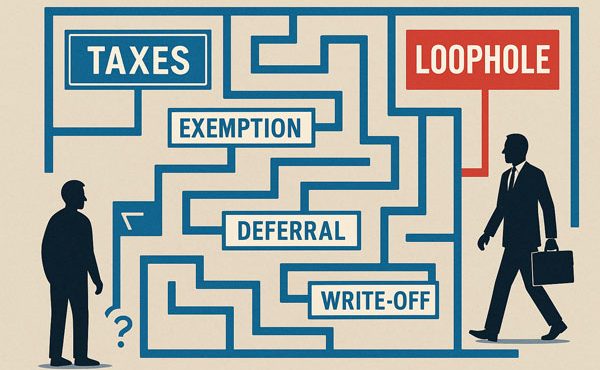

A striking parallel exists between the now-vilified single-family home and the modern high-rise: both are products of the same market-driven logic, built upon abstract financial models prioritizing profit over other critical variables. While their architectural forms differ, the economic and regulatory mechanisms that sustain them are virtually identical. As global wealth disparity and ecological devastation intensify, we see the results of this system: the concentration of wealth among a privileged few, often at the direct expense of the majority and our planet’s fragile ecosystems.

Beneath the sleek facades of contemporary high-rises lie a host of challenges: significant carbon emissions embedded in their materials, excessive energy demands throughout their lifespans, and detrimental impacts on the surrounding urban environment—from overshadowing public spaces to creating microclimates that make streets less hospitable. These costs, often invisible in standard financial calculations, distort our perception of high-rises as the inevitable or even optimal solution to urban growth.

Adding to this illusion of inevitability is the influence of visual media, which shapes public perceptions of what a “modern city” should look like. The repeated imagery of high-rise skylines in movies and other popular media fosters the belief that towers are the natural and unavoidable future of urbanism. Yet, studies suggest that cities built on alternative spatial models often outperform their high-rise-dominated counterparts across many categories.

It is important to recognize that, like any dominant building typology, high-rises do offer advantages. However, these benefits reflect the values of the culture that produces them. Contemporary residential towers excel at one thing in particular: generating wealth for speculators, investors, and developers, along with their associated consultants. This is not to dismiss the real risks involved in development, but in a market-driven system, projects would not proceed unless the rewards outweighed those risks.

The rise of the high-rise is not merely an architectural trend—it is an economic and regulatory ecosystem that has optimized itself to sustain and perpetuate this building type, just as the single-family home once did. Today, financial lending practices, municipal zoning policies, and development incentives have all been tailored to promote high-rise construction, making alternative models increasingly difficult to envision—especially for those embedded within the system.

This article marks the launch of Rising High, Falling Short, a multi-part series critically examining the underexplored consequences of contemporary high-rise urbanism and the biases that reinforce its dominance. Unlike the oversimplified narratives often provided by politicians, developers, and industry consultants, this series seeks to navigate the complexities of urban development with nuance and depth.

Cities are intricate, evolving systems, and one-size-fits-all approaches often do more harm than good—especially when discussions about urban development are increasingly shaped by cherry-picked data and fear-based messaging in municipal decision-making.

This series builds upon our broader research efforts, including S101S, The Barcelona Chronicles, Learning from Moses, and When Care Becomes Control: The Hidden Violence of Urban Planning. These foundational works have provided critical insights into the structural forces shaping our cities, setting the stage for deeper analysis.

A Shift in Focus

The Pro Forma Problem, the final article prepared in 2024, marked a deliberate shift—from laying the groundwork to challenging entrenched assumptions in contemporary planning discourse. The backlash it provoked was anticipated and, in many ways, validated the necessity of this continued work.

Anticipating the inevitable criticisms—that this series is “anti-density” or rooted in NIMBYism—let us be clear: density is not synonymous with high-rises. In fact, when considering factors like access to natural light and open space, high-rises are not even the most spatially efficient form of urban development. Alternative models balance density with environmental sustainability, social cohesion, and long-term livability—many of which have been successfully implemented worldwide. This series will explore those as well.

At its heart, Rising High, Falling Short is not merely about pointing out the flaws of high-rise urbanism; it is about asking how we can do better. It challenges the assumptions that guide current urban development and, instead, pushes for solutions that serve both people and the planet.

As cities confront the overlapping crises of climate change, housing affordability, and social inequity, we must be skeptical of those who claim there is only one path forward. By examining the full picture—including carbon footprints, ecological loss, and social impacts—we can begin to envision a more balanced and responsible approach to growth.

A New Format for Informed Debate

Like the S101S series, Rising High, Falling Short will feature a multi-section format. Each piece will begin with a Key Metrics Summary—a concise breakdown of relevant data, including figures our team has calculated with input from a well-informed community.

This will include an estimate of “Social Costs” in Canadian dollars, when possible—a measure of the economic impact of particular elements. For example, the Social Cost of Carbon Emissions represents the economic damage caused by emitting CO₂, accounting for climate change, health effects, and environmental degradation. Including these figures allows the public to factor these “externalities” into financial models—such as pro formas—that rarely acknowledge them. The inclusion of “Social Costs” is also ann invitation to question the numbers placed on these complex issues. After all, is it possible to put a dollar cost something like climate change or environmental degradation?

To make complex numbers more relatable, the Key Metrics Summary will also feature “Everyday Equivalents and Comparisons”, translating abstract data into tangible real-world examples.

The article will then proceed with:

- “Context”, which provides background on the issue at hand.

- “So What?”, which connects the data to the broader narrative.

- “Food for Thought”, which presents alternatives and precedents for consideration.

We are not stopping there, though!

For those eager to scrutinize our assumptions, the final section, “Calculations and Assumptions”, will provide full transparency. Unlike many who hide behind disclaimers and jargon, we welcome informed debate and critical engagement. This series is an invitation to that conversation.

So…welcome to Rising High, Falling Short!

Let’s explore what it means to build smarter, greener, and more equitably—for the cities of today and the generations to come.

***

Other articles in the Rising High, Falling Short series:

- Rising High, Falling Short: Construction-Related Carbon Emissions

- Rising High, Falling Short: Social and Economic Division

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.