Just because there’s a number on it, it doesn’t mean that the number was arrived at properly…people gather statistics. People choose what to count, how to go about counting. There are a host of errors and biases that can enter into the collection process, and these can lead millions of people to draw the wrong conclusions.

Daniel J. Levitin, A Field Guide to Lies

There’s a new term gaining traction in planning circles: the “Coriolis Effect.” At first glance, it sounds like something pulled from a physics textbook—and it is—but it’s quickly evolving into a metaphor for the subtle yet consequential forces that quietly steer urban planning off course. Specifically, we’re talking about market-driven priorities that skew the trajectory of cities, often sidelining equity and sustainability in the process.

Urban planning is often described as a delicate balance—a fusion of science, art, and no small amount of political intrigue. Recently, the term “Coriolis Effect” has entered the discourse, not merely as a physics phenomenon but as a metaphor for the unseen forces that nudge urban development onto problematic paths.

Where does the phrase come from?

The term originates from Coriolis Consulting Corp., a respected Vancouver-based firm providing analyses for municipalities across North America, including Vancouver’s Broadway Plan. Over time, it has become shorthand for similar consultancies influencing the hidden choreography of city planning. Although many claim to offer “creative” solutions to contemporary urban challenges, the result often defaults to a predictable tune: the steady rhythm of market-driven priorities.

Just as the natural Coriolis force subtly bends trajectories on Earth, the economic biases embedded in Coriolis’s (and similar firms’) analyses gently—but significantly—redirect urban development. The result? Cities guided by the compass of financial feasibility, often at the expense of human and environmental needs.

At the core of these analyses is an almost religious adherence to market feasibility. Yes, economic viability matters—no one wants to build ghost towns—but this narrow focus frequently tips the scale away from crucial concerns like inclusivity and sustainability. Financial models tend to prioritize developer returns above all else, leaving little space for tenant stability.

When tenant protections are acknowledged, they’re often framed as barriers rather than necessities. It’s a narrative that practically writes itself: make it easy for developers, and the city will flourish. Except, that’s rarely the case.

Consider the frequent reliance on static market assumptions. Projections often rest heavily on present-day economic conditions, as if markets were frozen rather than volatile, evolving systems. Tools such as Internal Rate of Return (IRR) and Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) are often avoided—not because they are flawed, but because they require future-oriented assumptions about rents, vacancies, and costs, introducing additional uncertainty. Instead, simpler present-day profitability metrics are favoured, resulting in models that feel less like precision instruments and more like blunt tools. Urban planning deserves better than cookie-cutter solutions patched together with fiscal duct tape.

Social equity—frequently cited but rarely prioritized—receives similar treatment. In redevelopment contexts, consultancies like Coriolis nod to tenant protections yet frame them as logistical challenges. Existing renters, facing displacement, are seen less as individuals and more as complicating variables in an otherwise tidy formula.

Landlord incentives are prioritized over tenant outcomes, and while reports gesture toward affordable housing, the real focus often remains on market-rate or near-market units.

The result?

Entire neighbourhoods morph into enclaves for upper-middle and upper-income households, sacrificing diversity on the altar of market efficiency.

Environmental sustainability fares little better. References to green infrastructure and emission targets, where they appear at all, often feel obligatory rather than transformative. Deeper concerns—such as the embodied carbon of new developments, construction energy demands, or the long-term impacts of densification—are typically glossed over. It’s akin to painting a forest green and calling it conservation.

Let’s not forget the risks of generalization. Take the Broadway corridor, for instance. Rich in diversity and layered with history, its neighbourhoods are too often distilled into a series of broad-stroke assumptions. In the hands of market-focused consultancies, unique landscapes are reduced to one-size-fits-all models, undermining the nuanced character that makes each area distinct.

Community engagement, often heralded as central to modern planning, is reduced to a procedural checkbox. Aggregated data replaces lived experience, and local nuance is lost to the relentless tide of market logic.

These underlying biases aren’t dormant—they radiate outward, shaping city life. Gentrification gains speed. Long-time residents and small businesses are displaced in favour of wealthier newcomers. This isn’t “revitalization”—it’s a corporate facelift. And the short-term obsession with financial feasibility comes at the cost of long-term adaptability and resilience.

Urban planning should anticipate and adapt to future challenges, but static projections and risk-averse models delay meaningful evolution. Consultancies clinging to existing paradigms rarely innovate. They don’t ask: “What could be?” They ask: “What is the cheapest and most profitable?”

Like the real Coriolis force, these biases subtly redirect urban development—but trajectories can be corrected. By expanding success metrics to include social equity, environmental responsibility, and long-term resilience, urban planning can transcend market myopia.

Community voices must be elevated above spreadsheets. Cities are built by people, not profit margins. Environmental accountability must also shift from a perfunctory mention to a guiding principle. Planners must ask hard questions about carbon footprints, energy consumption, and climate resilience before it’s too late.

It’s time to reframe tenant protections as strengths, not liabilities. Stable, protected communities foster vibrant, enduring cities. Protecting renters is not just ethical—it’s strategic. Urban planning can evolve into what it was always intended to be: a tool for building cities that work for everyone, not just those who can afford to buy in.

The Coriolis Effect in urban planning reminds us that even subtle forces can have outsized impacts. By acknowledging these biases and working to counteract them, cities like Vancouver can ensure that their future is not just marketable but meaningful.

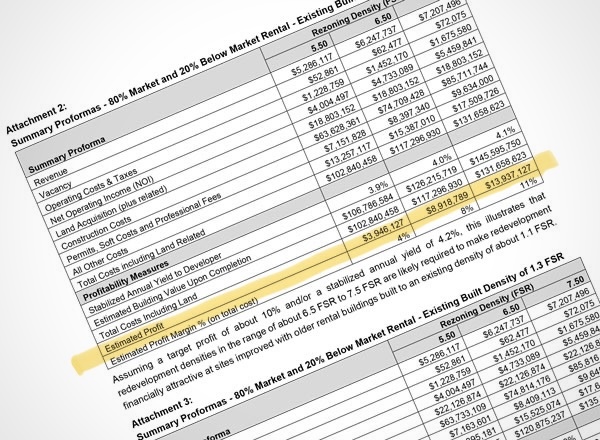

Appendix K of the Broadway Plan offers a perfect case study. Coriolis Consulting’s financial analysis reveals both the strengths and critical blind spots of the current approach. Take, for example, their reliance on static 2021 market conditions—an assumption that, even generously, feels optimistic. Markets are notoriously unstable. Baselines are necessary, yes—but treating “current” conditions as fixed realities constrains adaptive planning.

The analysis itself notes that “the pace of development will likely be modest,” particularly for rental housing, because many properties aren’t considered financially viable for redevelopment under current conditions. Yet rather than questioning whether these conditions should be challenged, the analysis treats them as natural facts.

Tenant protections—supposedly a centerpiece of the Broadway Plan—are framed as burdens. Measures like the right of return and temporary rent top-ups are described as adding “additional complexity, cost, uncertainty, and risk for developers”—the exact language used in Appendix K. This framing, while pragmatic on the surface, betrays a deeper truth: the lives and stability of renters are treated as secondary to smoothing the financial equation for redevelopment.

The implication is clear: tenant protections are liabilities, not assets. This invites scrutiny over whether such analyses serve the public interest or simply reinforce developer priorities.

Industrial and office development in areas like Mount Pleasant and Burrard Slopes is similarly reduced to simple profitability calculations. There is little exploration of how these spaces could nurture local economies, support innovation, or bolster employment diversity. The metric remains: how quickly can developers make a return?

Turning to the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation’s rental market reports—often cited alongside such analyses—a familiar pattern emerges. CMHC offers critical vacancy and rent data but again relies heavily on aggregate trends.

A 1.1% vacancy rate screams of an affordability crisis—but without further disaggregation, it tells us little about who is actually affected. Low-income renters, seniors, and marginalized communities remain invisible within these averages, while gentrification, tenant displacement, and the erosion of naturally affordable housing are rarely examined with the depth they deserve.

Moreover, CMHC data excludes critical segments like condo rentals and secondary suites, presenting only a partial view of the rental landscape. The low vacancy rate, often interpreted as a lack of supply, might instead indicate tenants clinging to rent-controlled units, fearful of entering a punishing market.

Ultimately, CMHC’s emphasis on market dynamics risks reinforcing the very inequities it seeks to illuminate. By focusing on averages and trends, the human stories behind the data are obscured. For instance, a rise in average rents might signal robust demand to one reader, but to another, it’s a story of families being priced out of their neighbourhoods. Without a more nuanced approach, CMHC’s reports can unintentionally bolster pro-development narratives that prioritize profitability over people.

Ultimately, both Coriolis’s and CMHC’s frameworks privilege market logic. Understandably, then, the resulting conclusions are remarkably aligned—and profoundly limited.

To be clear: the problem isn’t the numbers, but the assumptions behind them.

As the old saying goes, “Everything looks like a nail when you’re a hammer.” When trapped in market orthodoxy, every planning question looks like a feasibility study.

Market dynamics are not immutable truths. Yet too often, both public institutions and private consultants treat them as such. By resisting a more holistic lens, these institutions risk perpetuating cycles of exclusion and inequity.

But—like the real Coriolis Effect—these forces can be countered. Through transparency, critical analysis, and a re-centering of human and environmental values, we can push back against the gravitational pull of market thinking and chart a more equitable course.

***

The Coriolis Effect Series:

- The Coriolis Effect, Part I: Planning by Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part II: Beyond the Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part III: Reclaiming the Planner’s Toolkit

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.

One comment

Well said.