In British Columbia, ordinary homeowners pay annual property taxes—and when they buy a home, they pay Property Transfer Tax. In recent years, the Province and the City of Vancouver have introduced new taxes to curb speculation: the Empty Homes Tax, the Speculation and Vacancy Tax, and the recent Flipping Tax. These policies suggest a government serious about housing fairness.

But is that fairness evenly applied?

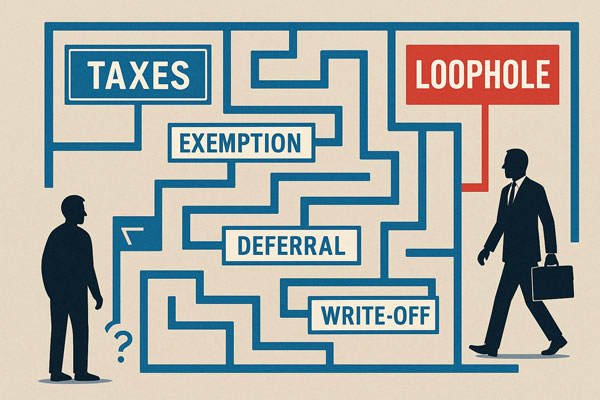

While individual homeowners face rising bills and pay taxes predictably, large landowners, corporate landlords, and developers operate within a parallel system—one shaped by exemptions, deferrals, and loopholes that shield them from the obligations ordinary citizens routinely meet.

To understand the current state of housing, it’s critical to examine how tax policies across all levels of government—federal to municipal—have quietly become tools to subsidize speculation. And while they’re often framed as incentives to “get housing built,” the evidence suggests they are just as often used to hold land, avoid risk, and capture value.

Because in today’s housing system, it’s not just what you build—it’s what you can avoid paying for.

Vancouver’s housing crisis is often framed as a supply issue, prompting successive governments to roll out incentives aimed at accelerating development. However, while the public narrative emphasizes urgency and generosity, a quieter story unfolds behind the scenes—one of tax breaks quietly engineered, aggressively lobbied for, and systematically exploited by the development industry.

Across all levels of government, tools originally intended to support essential housing have increasingly become instruments of private gain. In the name of affordability and revitalization, public money is subsidizing delay, speculation, and profit.

The built environment doesn’t emerge through isolated decisions, but from a shared “building culture”: a network of rules, habits, roles, and relationships between diverse actors. When the fiscal foundations of that culture begin to tilt toward private benefit, the entire system drifts off course. In Canada broadly—and Vancouver specifically—evidence suggests that tax policy has quietly become a tool for inflating land values rather than delivering homes.

This drift does not appear accidental.

The history of “obsolescence” offers key insights into a taxation and regulatory regime that appears structurally biased toward profit-making. The idea that buildings naturally “age out” of usefulness is not a physical inevitability—it was invented. First introduced by the U.S. Treasury in the early 20th century to allow tax write-offs, the concept quickly became a convenient tool for real estate lobbies and accountants. It provided financial justification for demolishing functioning buildings in favor of newer, more profitable ones.

Tax rules helped entrench this mindset. Accelerated depreciation allowed property owners to write off buildings more quickly, making demolition and redevelopment more attractive than maintenance or reuse. Obsolescence, in this context, became a financial strategy—less about a building’s condition than its profitability.

In Vancouver, this logic manifests in policies like the Development Potential Relief Program and exemptions from Development Cost Charges (DCCs). A building isn’t evaluated by its use or who it shelters, but by what more profitable development could replace it. Aging structures are seen not as assets but as obstacles, and tax incentives are used to hasten their removal. These policies are not neutral—they are part of a fiscal framework that aligns public money with private return.

When governments reward demolition over adaptation, and speculation over stewardship, they’re not merely enabling developers—they’re shaping an increasingly unaffordable city.

And this isn’t just Vancouver’s story.

At the federal level, Canada continues to reward short building lifespans through programs like the Capital Cost Allowance (CCA) and the Accelerated Investment Incentive. These allow buildings to be depreciated at rates up to three times faster than normal, encouraging a pattern of constant redevelopment.

These tax rules don’t look like subsidies, but many experts argue that’s exactly what they are: indirect financial incentives that make demolition more appealing than reuse. They reflect the obsolescence logic that scholars have long warned about—treating buildings not as long-term infrastructure, but as short-term investments.

Paired with local tax breaks, these national policies fuel a development model driven by turnover. Taxpayers foot the bill for a system that treats longevity as inefficiency.

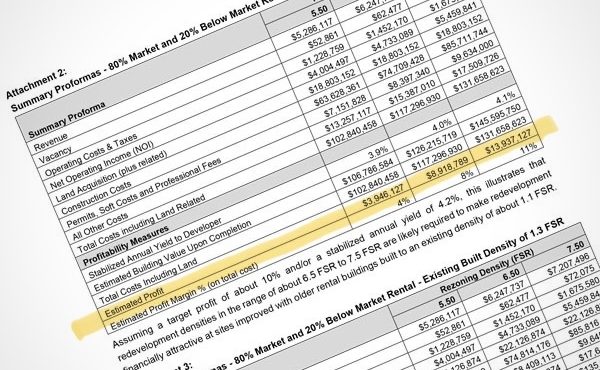

Crucially, these subsidies don’t necessarily lower the cost of housing—they inflate the price of land, benefiting current landowners while raising the barriers to delivering truly affordable housing. Economists have long observed that development incentives are often capitalized into land value.

In Vancouver, where land is the most volatile and speculative component of housing costs, even minor policy shifts can spark dramatic fluctuations in price. Lower taxes or deferred fees rarely translate into affordability for buyers or renters. Instead, they raise the price developers must pay to acquire land—profits that are often captured by landowners, not builders—reinforcing cycles of speculation, delay, and displacement.

This suggests that tax reform alone will not deliver affordability unless paired with mechanisms to prevent windfalls. As subsidies shift, so does the land price residual. If unregulated, those changes are simply captured by landowners.

Collectively, these exemptions, write-offs, and delays don’t just reduce developer costs—they systematically transfer the fiscal burden of urban growth onto ordinary taxpayers. They signal a larger shift: from a “user pays” model to a “public shoulders risk” regime, where capital gains are privatized and infrastructure costs socialized.

As sales slow and projects collapse, Ottawa is considering federal intervention to “kickstart” the market—underscoring the troubling logic that when speculation falters, the public must step in. Rather than correcting the system, governments appear poised to underwrite its failure.

And real estate isn’t the only sector operating under this model.

Across the Canadian economy, public subsidies flow toward industries built on extraction and churn. Oil and gas companies receive billions in tax breaks and accelerated write-downs. Clean-energy firms benefit from generous investment credits and fast-tracked depreciation. Even agriculture receives supports that stabilize revenue while limiting transparency.

These policies do more than support activity—they signal what kinds of value our institutions prioritize. As with real estate incentives, they reward speed, disposability, and circulation. The deeper message: building things to last is a liability.

In this light, real estate subsidies aren’t an exception—they are part of a broader public-finance regime that encourages private turnover at public expense.

How did we get here?

The rise of the modern developer mirrors a centuries-long shift—from hands-on building grounded in community ties to finance-driven coordination aimed at market returns. Where local builders once shaped neighbourhoods through physical labour and community relationships, developers emerged in the 18th and 19th centuries as financial coordinators. They didn’t build—they assembled land, secured capital, commissioned designs, and sold units.

Their role prioritized financial timing and market return, not community outcomes. That logic—centered on capital, not care—remains dominant today. Tax policy is deeply embedded in this system, smoothing the path for delay, speculation, and profit-taking.

Programs like Vancouver’s Empty Homes Tax refund or density bonusing don’t just reflect flawed policy—they reveal a system that rewards those best positioned to exploit it.

Here are some of the most common and consequential ways tax policy is being subverted:

- Empty Homes Tax Refunds: A Case Study in Retreat – The Empty Homes Tax (EHT) was meant to penalize vacant units during a housing emergency. But in 2022, Vancouver Council refunded $3.8 million in EHT to developers who had failed to sell 60 unsold condos. The rationale? Sluggish sales. But this was not a supply issue—it was an oversupply of unaffordable housing. By shielding developers from market risk, the City effectively reversed the intent of its own policy.

- Development Potential Relief Program: Rewarding Land Banking – The Development Potential Relief Program (DPRP) provides property tax breaks for land flagged for future development. Originally designed to support small businesses, it now applies to more than 700 properties—many held by major landowners. In practice, it rewards those who sit on land rather than build on it.

- Vacant Lot Tax Shelters: Astroturfed Gardens as Loophole – Developers can reduce their tax burden by converting demolition sites into nominal “community gardens”—often fenced-off lots with minimal landscaping. BC Assessment may reassess such sites at a lower rate, offering substantial tax relief during speculative hold periods.

- Waived Fees, Conditional Promises – Development Cost Charges (DCCs) are meant to fund infrastructure for new housing. Yet in B.C., they’re often waived for projects claiming affordability. Some for-profit developers partner with non-profits to qualify, while retaining control of rents and ownership. Public money, private gain.

- Assessment Averaging and the Delay Dividend – Even after rezoning, developers benefit from delay. Vancouver’s five-year assessment averaging smooths property tax increases, allowing developers to hold onto land while waiting for market peaks, with minimal cost. While this raises concerns for speculative holders, it also protects non-speculating homeowners impacted by area-wide rezonings from being taxed out of their homes.

- Under-Assessed and Overpowered – Developers benefit from the structural weaknesses of BC’s property assessment system. Former BC Assessment official Derek Holloway revealed how large industrial, commercial, and investment (ICI) properties are routinely undervalued. Limited disclosure, opaque transactions, and lax authority allow major landholders to avoid fair taxation—shifting the burden onto homeowners and small businesses.

- Assessment Bias and Heritage Erosion – The assessment model favours redevelopment by undervaluing older buildings and overvaluing land based on “highest and best use.” This discourages maintenance and inflates prices. Recent legislative changes (Bill 44) stripped municipalities of the ability to protect heritage through new agreements, leaving preservation in legal limbo.

Vancouver’s developer-friendly tax environment isn’t just shaped by direct subsidies—it’s sustained by a tangle of exemptions, loopholes, and quiet policy reversals.

For example, Vancouver City Council removed the time limit on the Empty Homes Tax (EHT) exemption, allowing indefinite waivers for unsold units. Entire rental buildings can be exempt from the EHT if just one unit is occupied, enabling landlords to keep properties largely vacant while circumventing tenant protections. Meanwhile, developers continue to exploit a longstanding loophole in the Property Transfer Tax (PTT) through share sales and bare trusts—a workaround that Ontario eliminated decades ago.

Between 2021 and 2023, Development Cost Charge (DCC) exemptions for Below-Market Rental projects averaged $80,000 per unit. In October 2023, Council further amended existing Housing Agreements to raise allowable rents and eliminate vacancy control—transforming what was intended as a public benefit into a private windfall.

One notable example is CURV, a 60-storey luxury tower that received public support but later removed its below-market housing commitments with little accountability. Interestingly, CURV recently entered receivership, a legal process triggered when a borrower cannot meet financial obligations and a court-appointed receiver takes control of the project to recover debts.

This highlights a saturated luxury condo market and the risks of subsidizing high-end projects that fail to meet public needs. Despite its collapse, the project had already benefited from exemptions and policy leniency, underscoring how the public increasingly shoulders private risk.

These changes may seem minor, but they reflect a deeper shift: public institutions are increasingly absorbing private risk rather than ensuring public outcomes.

Now, if stealth, speed, and complexity are the ingredients of modern planning control, as I argued in The Trifecta of Control, then tax policy is the sauce they simmer in. This next section walks through how tax tools—federal to municipal—have been bent toward private interest, forming a parallel trifecta: one of tax-driven control.

Federal Redirection: CMHC and the Rental Shift

At the federal level, the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) has quietly repositioned itself as the country’s leading enabler of institutional rental development. In 2024, it insured over 283,000 rental units, compared to just 49,000 homeowner loans.

Programs like MLI Select provide public guarantees for large-scale rental projects, often with flexible or minimal affordability requirements. This shift doesn’t just follow the market—it shapes it. CMHC’s tools increasingly support a system where institutional landlords dominate—especially Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), which now own a growing share of Canada’s rental stock. These shareholder-driven entities prioritize investor returns over tenant well-being, raising broader concerns about housing as a financialized commodity rather than a social good. Public risk backs private return.

While a rental-first approach may reflect today’s economic realities, it raises broader concerns: about equity, long-term resilience, and who ultimately controls the housing system. CMHC’s evolving role deserves scrutiny—not just for what it builds, but for whom—as it has become a central planner in all but name and is distributing risk through public channels, while control and returns remain private.

Provincial Alignment: Subsidies Go Province-Wide

In July 2025, the BC government changed how development charges are collected. Now, 75% of fees can be deferred until occupancy, offering developers what amounts to an interest-free loan. Surety bonds replaced letters of credit, further lowering financial barriers.

At the same time, municipal borrowing limits were raised, allowing cities to absorb more infrastructure costs without public referendums. These changes were framed as pragmatic responses to rising construction costs, but in practice, they shift risk from private developers to public budgets.

What was once an exception is becoming policy. The Province is no longer just enabling a developer-first approach—it’s actively underwriting it.

Municipal Incentives: Relief Over Accountability

In June 2025, Vancouver introduced a new round of developer incentives: deferred Development Cost Levies (DCLs), reduced Community Amenity Contributions (CACs), and a freeze on inflation adjustments. These policies were shaped in close consultation with a developer working group—underscoring the city’s shift toward safeguarding project viability over public return.

Even with added perks, many projects still don’t “pencil out.” Meanwhile, renters face demoviction as their homes await speculative replacement. The city’s retreat from the principle that development should fund public benefit is stark.

Where Vancouver once led in capturing land value uplift, it now uses public tools to preserve private margins. Relief, in this case, doesn’t deliver—it defers accountability.

This shift isn’t subtle—it’s strategic. When profitability falters, public institutions are expected to fill the gap.

A Broader Pattern of Abuse

Time and again, tools built for the public good are repurposed for private gain. Community Revitalization Levies (CRLs)—used in other Canadian jurisdictions and enabled by B.C.’s Community Charter —fund infrastructure that directly benefits nearby landholders.

In Vancouver, Community Amenity Contributions (CACs)—once meant to fund parks, childcare, and public amenities—are increasingly reduced, deferred, or waived entirely in the name of “affordability.” Loose affordability definitions let developers offer near-market units while collecting public subsidies. Federal GST rebates meant for buyers are folded into pre-sale pricing, with upsold finishes used to preserve developer margins.

This isn’t creative accounting. It’s a system functioning as intended—one where value is extracted, not created.

If Vancouver—and other Canadian cities—want a housing system that serves people rather than profit, they must stop handing out blank cheques. Every subsidy should be tied to firm requirements: binding timelines, deep affordability, shared ownership models, and real penalties for delay or manipulation.

Because when we subsidize speculation, we don’t just lose money…we lose time. Time that could be spent building the right homes, in the right places, with the right safeguards.

And in a housing crisis, time is the most unaffordable cost of all.

***

Related Spacing Vancouver pieces:

- The Slow Emergency

- Trifecta of Control: Stealth. Speed. Compexity

- Entitled to Flip

- When Local Planning Becomes Provincial Command

- The Coriolis Effect (3 part series)

- When Care Becomes Control

- The Broadway Plan Blues

- Learning from Moses

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.