In my earlier Coriolis Effect series (Part I, Part II, and Part III), I argued that city planning has been quietly absorbed into the logic of the developer’s spreadsheet. What once was a public toolkit for shaping collective futures has narrowed into a calculator for financial feasibility. The Broadway Plan shows this with unusual clarity. Here, the fate of Vancouver’s central corridor is being tested not against public purpose or vision, but against the hard edge of what “pencils out.”

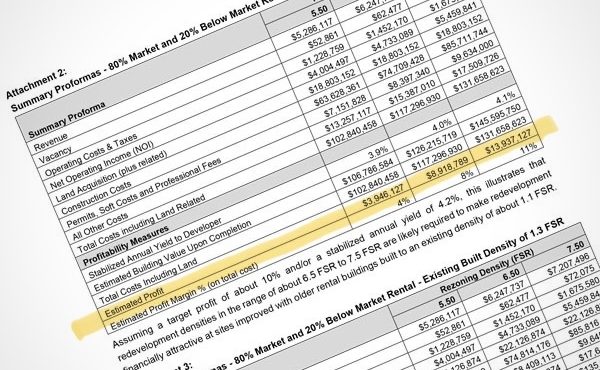

Appendix L of the July 2025 implementation report, prepared by Coriolis Consulting, looks harmless at first glance: just another set of tables, formulas, and yield calculations. Yet hidden in those rows and columns is a quiet revolution, foreshadowed in the Slow Emergency. The task of city-building has been reduced to a single, haunting question: what must the city give so that developers will build?

Numbers replace narratives. Land becomes a cell entry, redevelopment costs another. When the gap between the two produces enough uplift, the green light flashes. If not, nothing happens. The spreadsheet has stopped being a tool and become an oracle—its pronouncements treated as prophecy.

A recent FOI document—requested by Andrea Miller as a part of a CRD Watch investigation—pulls back the curtain and reveals the oracle’s authors. Behind the scenes, a tightly connected network of consultants has been writing the formulas that dictate Vancouver’s future. Coriolis Consulting appears again and again, shaping everything from the Broadway Plan to province-wide housing reforms. Some of these actors simultaneously advise the City while advocating publicly, blurring the line between independent expertise and vested interest.

Public hearings and op-eds begin to resemble choreographed performances—where key actors are already contracted to implement the very policies they’re defending.

The FOI also exposes the pressure cooker in which these decisions were made. Provincial housing bills—44, 46, 47—imposed a non-negotiable compliance deadline of June 30, 2024. One internal email captures the mood perfectly: “We’re still trying to keep our heads above water,” wrote a senior staffer as the date loomed.

With staff overwhelmed and time running out, cities leaned heavily on external consultants to meet provincial mandates. The Province sweetened compliance with $51 million in “capacity funding”—a mix of carrot and stick. Municipalities were paid to align quickly, not to deliberate deeply. In this context, outsourcing wasn’t a strategic choice—it was survival.

But oracles are never neutral. This one speaks in absolutes but harbours blind spots. It assumes landowners will sell once the numbers break even, though many expect premiums—often 20 to 30 percent above what the sheet labels “viable.” It treats apartment blocks full of tenants as mere variables, not as homes with memories, social ties, and fragile livelihoods.

Worse, it freezes time itself.

Interest rates, absorption, presale values—these are locked in as constants, even though zoning will outlive this market cycle and the next. It is like designing a city for the climate of a single afternoon, then living with the consequences for a generation.

This is a dangerous dynamic: pro formas are snapshots of a moment in time, while urban plans are meant to guide cities for decades. When long-term visions are based on short-term financial assumptions, instability ensues.

The staff memo that accompanies Appendix L embraces this logic almost without question. Redevelopment is no longer viewed as a civic choice but as a financial threshold. If the numbers work, towers rise; if not, concessions follow. Affordable housing is reduced to a footnote, offered only when it doesn’t erode investor returns.

Affordable housing becomes a footnote—offered only when it doesn’t erode investor returns. Amenities become bargaining chips, traded away when margins tighten. Displacement disappears from the ledger, as though a family forced out of a walk-up never existed.

Reading these documents, one can’t help but picture density being rationed like oil. Two to five towers per block face. Height caps and floor space ratios held like barrels to be released at carefully measured intervals. It has the feel of OPEC more than urbanism: a cartel of scarcity, where development rights—or “Vitamin D”—are monetized long before they are delivered.

The irony is sharp: in trying to manage the pace of growth, the City ends up inflating the very land values it claims to regulate. Scarcity breeds speculation, and speculation drives the cycle ever faster.

Moreover, land values are shaped by zoning and policy choices, meaning pro formas are not fixed truths but contingent narratives built on those assumptions.

This is not city-building. It is deal-making, dressed in the language of planning. The question animating the Broadway Plan is no longer “What kind of city do we want?” but “What kind of city will pencil?”

Public purpose bends to private feasibility—not the other way around.

To be clear, ignoring economics would be naïve. Feasibility matters. But treating it as destiny is equally reckless. A pro forma should inform deliberation, not dictate it. Alongside financial yield, we must measure other values: tenants retained, affordable stock preserved, carbon emissions avoided, equity advanced, to name a few.

A city’s health cannot be reduced to a return-on-investment hurdle.

Broadway is a warning shot. When viability becomes the sole measure of possibility, democratic choices are quietly foreclosed. Futures that don’t “pencil” are abandoned before they are even imagined. The spreadsheet’s neat rows conceal the messy realities of eviction notices, moving vans, and lives uprooted. They flatten human stories into residual land values.

The FOI makes clear that the Broadway Plan was never an one-off—it was the prototype. The same consultants and the same models are shaping rezonings across BC. Bills 44, 46, and 47 have scaled up the Broadway Plan logic, embedding planning-by-spreadsheet into provincial law. If Broadway Plan feels like a parable today, it is because the story is being retold in every municipality, each with its own cast of consultants, deadlines, and compliance incentives.

And if the initial Coriolis Effect trilogy traced the dangers of planning by spreadsheet in theory, the Broadway Plan is the parable made real. It shows how quickly vision can shrink to a matter of margins and uplifts, how a public plan can begin to resemble a private ledger, how economics can displace ethics.

It also reveals how developer- and finance-led housing narratives elevate certain actors (developers, consultants, financial analysts) and forms of knowledge (pro formas, “market viability”) while erasing or sidelining others including lived experiences of tenants, displaced communities, ecological impact, and others outside of market logics.

So, how do we move forward?

The challenge now is not only to critique—but to imagine and demand—futures that no spreadsheet can capture. Futures that speak in the language of care, justice, and ecological responsibility. Because while numbers can tell us what is feasible… they cannot tell us what is just.

***

The Coriolis Effect Series:

- The Coriolis Effect, Part I: Planning by Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part II: Beyond the Spreadsheet

- The Coriolis Effect, Part III: Reclaiming the Planner’s Toolkit

- The Coriolis Effect, Part IV: When Viability Becomes Destiny

**

Other related articles:

- Entitled to Flip

- The Slow Emergency

- The Slow Emergency, Part II

- The Trifecta of Control

- When Care Becomes Control

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.

2 comments

It’s a side comment to your point, but CRD watch, the organization you have credited with releasing information on Coriolis, are a far-right organization who are dedicated to preventing the construction of new housing as a means of preventing non-white people from moving the the greater Victoria area. They often advocate for harsher treatment of homeless people, more police in schools, a more car-reliant transportation system, and reducing the role of First Nations in regional government.

Hi Wim,

Thank you for sharing this context.

To clarify, my reference to CRD Watch in the article was solely to credit the party that filed the FOI request. This is standard practice and would have been done regardless of which individual or organization made the request. The FOI document itself—and the information it contains—are official government records, independent of the views or positions of the requester.

Thanks again for your comment and for helping to ensure the discussion remains informed and constructive.

Best,

E