Vancouver Heritage Foundation would like to thank our guest writer for this weeks article, Marta Farevaag, urban planner and Principal of PFS Studio.

Heritage advocates and urban designers alike bemoan the redevelopment projects around Vancouver that retain just the facade of an earlier building, especially one with architectural and contextual merit. When the 1911 Hudson’s Bay Insurance Company building facade was stuck onto the side of the Bank of Canada Building (now the CMA building) at 900 West Hastings (see image below), it was as an afterthought in the redevelopment of the block back in the mid-60s. The way we incorporate facades into new developments has changed over the years.

Nevertheless, facades with substantially new buildings behind them continue to be part of some recent developments. In most cases, the retained facades belong to buildings on the City’s Heritage Register and have key roles in establishing the streetscape character of their blocks. Each example of facadism has a unique story as to how and why decisions were made. With the policies and tools available to the City of Vancouver, the design solution usually results from attempts to save a meaningful proportion of a heritage building that are thwarted by challenges in engineering, seismic stability, poor material conditions discovered by testing, and, of course, financial.

Nevertheless, facades with substantially new buildings behind them continue to be part of some recent developments. In most cases, the retained facades belong to buildings on the City’s Heritage Register and have key roles in establishing the streetscape character of their blocks. Each example of facadism has a unique story as to how and why decisions were made. With the policies and tools available to the City of Vancouver, the design solution usually results from attempts to save a meaningful proportion of a heritage building that are thwarted by challenges in engineering, seismic stability, poor material conditions discovered by testing, and, of course, financial.

Heritage conservation projects are guided by federal and provincial standards that seek maximum respect for the historic fabric and make facadism a strategy of last resort. These standards are embedded in City heritage policy. In recent years, every heritage project requires a professionally prepared Statement of Significance that identifies key building features that should and can be retained during redevelopment. These Statements become the basis of negotiation among City staff from involved departments, the developer, architect, engineer, and others at the table.

With standards and policies in place, it is interesting to ask why facadism still occurs. Vancouver Heritage Foundation has been sponsoring a lunch and learn series for three years. Many of the invited speakers have been the architects, developers, and heritage consultants of recent projects. They tell the story of how the project started out and the many twists and turns, discoveries and soul searching that led to the final design. For example, internal program changes within the Downtown Robert Lee YMCA (pictured left) reduced the amount of old building retained from concept to construction. The Woodwards redevelopment considered a range of retention options before deciding to save only the oldest part of the complex and putting a new W on the roof while transforming the old one into public art at grade. The Cultch set out to retain much of the old structure but found unexpectedly poor material conditions when construction started that required last minute responses and the removal of existing materials.

With standards and policies in place, it is interesting to ask why facadism still occurs. Vancouver Heritage Foundation has been sponsoring a lunch and learn series for three years. Many of the invited speakers have been the architects, developers, and heritage consultants of recent projects. They tell the story of how the project started out and the many twists and turns, discoveries and soul searching that led to the final design. For example, internal program changes within the Downtown Robert Lee YMCA (pictured left) reduced the amount of old building retained from concept to construction. The Woodwards redevelopment considered a range of retention options before deciding to save only the oldest part of the complex and putting a new W on the roof while transforming the old one into public art at grade. The Cultch set out to retain much of the old structure but found unexpectedly poor material conditions when construction started that required last minute responses and the removal of existing materials.

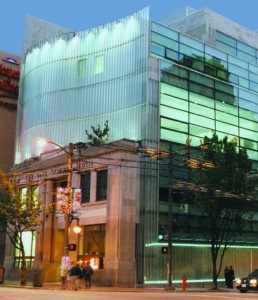

Projects that put similar new uses into a heritage building find it easier to work with old  interiors such as the Pennsylvania Hotel renovation which converted hotel suites into social housing. The developments that attempt to combine completely divergent programs tend to be less successful in keeping the interior. Sometimes cited as a prime example of facadism, The Scotiabank Dance Centre (pictured right) was adapted by Arthur Erickson from the 1929 Bank of Nova Scotia by architects Sharp and Thompson. The interior was one of the most intact bank buildings in the city and thus its loss proved to be controversial. The Skwachays Healing Lodge by Joe Wai Architects at 31 West Pender Street is also a prime example as it places a First Nations healing facility behind a protected Chinatown facade. The social value of the new use often supports the move towards substantial change behind the facade.

interiors such as the Pennsylvania Hotel renovation which converted hotel suites into social housing. The developments that attempt to combine completely divergent programs tend to be less successful in keeping the interior. Sometimes cited as a prime example of facadism, The Scotiabank Dance Centre (pictured right) was adapted by Arthur Erickson from the 1929 Bank of Nova Scotia by architects Sharp and Thompson. The interior was one of the most intact bank buildings in the city and thus its loss proved to be controversial. The Skwachays Healing Lodge by Joe Wai Architects at 31 West Pender Street is also a prime example as it places a First Nations healing facility behind a protected Chinatown facade. The social value of the new use often supports the move towards substantial change behind the facade.

Many heritage projects today are done with Heritage Revitalization Agreements, essentially a site-specific negotiated plan that considers costs and can grant incentives like more density and relaxation of building codes to arrive at a conservation strategy. Past projects, like Woodwards, achieved heritage retention by using the Transfer of Density policy to move potential density off site to nearby properties without heritage buildings on them. This powerful tool is on hold for the present making extensive heritage retention harder to achieve than it was for some past projects. Avoiding facadism will continue to be achieved on a project by project basis.

Good policy and standards help, but each heritage project remains a complex negotiation between conservation intentions and practical considerations. City staff needs to balance clear expectations of good heritage practice with openness to resolve emerging challenges in technical aspects and design. Financial considerations will be on the table. Developers and designers need to be creative with options to address heritage objectives.

Want to learn more about facades in Vancouver? Join us Wednesday March 27th 12pm, at the BCIT Downtown campus as we hear from the architects regarding the challenges, considerations, and eventual decisions that lead to this style of incorporation of the historic Quadra Club into a new development at 1021 West Hastings.

Marta Farevaag is an urban planner and Principal of PFS Studio with a longstanding interest in heritage and the evolution of Vancouver. She is currently Chair of Vancouver Heritage Foundation’s Board of Directors and a coordinator of Brown Bag Lunch and Learn talks.

Featured image: Taken March 26, 2013. Support structures holding up the remnants of the University (Quadra) Club building at 1021 West Hastings.

Photo Credits:

Robert Lee YMCA – Downtown Vancouver, B.C. detail. vfj.drupalgardens.com. Robert.Crow, July 2011.

Scotia Dance Centre, detail. www.willgoto.com copyright Tourism Vancouver, John Watson. 2013.

One comment

Facadism is an euphemism that allows the partial destruction, the reductionism to a bi-dimensional ornamental epidermis by dissecting elements from the original corpus, disregarding its core values and collective memory, subjective for stentorian appearances. It is certainly appealing to the pragmatist who is comfort and ease at the design table.

The façade retention argument fails to incorporate the historical meaning into the architectural unit, and at a larger scale, to the city. The current needs of the city does not require mere additional square footage but a complete reconciliation with its past, that for being recent is still fragile.

Vancouver under the excuse of being a young city fails to control its late heritage and is seduced by oversimplified exercises that attempt to practice of architecture as a whole.

The Standards and Guidelines for the Conservation of Historic Places in Canada, framed under the ICOMOS Burra Charter, has as primary purpose in the protection of the significance of the place. Given the charter’s mandate professionals, stakeholders and civil society should look for an intensive interpretation of the past.

Architecture encompasses better than any other cultural activity the history of humanity, especially for being egalitarian and easy to access, as it can be enjoyed publically. A clear example is as tourists, in New York, Barcelona or Rome we mainly consume architecture.

Undoubtedly a masterpiece of the last century can cohabit together with a contemporary one. It will be in the gifted hand of the designer and a knowledgeable client to find the correct balance; because this marriage cannot be staged, and should be based on ethics and aesthetics.

For its compositive structure, magnitude, and temporal narrative, literature can be considered closer to architecture than any other classical arts, And just as a good novel, or short story, it can be partially enjoyed; but a careful selection of chapters, excerpts and pages will bring forward a comprehensive account of the piece. A façade, like a prologue, or an epigraph, will fail to say much about the foregone ensemble and its magic realist journey.

“Take proper care of your monuments, and you will not need to restore them” Ruskin

(Hector Abarca is called architect in Spain, Poland, Italy, Sweden where he had studied Diagnosis & Rehabilitation of Building, Urban Revitalization, Culture and Development and Management of Heritage sites, and in Peru where he is licensed. In Canada is called Hector, and rarely Intern Architect.)