In the 1960s, Jane Jacobs stressed the importance of inclusivity in cities, as without it, “a city tends to become a collection of interests isolated from one another”. Vancouver is no exception in this regard. Voted simultaneously the world’s most livable city and North America’s least affordable city, Vancouver is a popular place where scarcity and affordability have been perpetual issues for decades.

Its recent urban and architectural developments show the polarizing directions the city might be heading towards. This is especially the case in Vancouver’s Downtown-Eastside (DTES), where opinions on recent developments are divided to the extreme, on many levels. This was recently reflected at the Urbanarium Society’s Vancouver Debates I kick-off event, where prominent experts in housing, urban planning and architecture were invited to discuss the pros and cons of density in the city.

Missing from this debate were the ordinary people and members of grassroots organizations, such as the Carnegie Community Centre Association that is dedicated to protect the rights of DTES’s long-term, low-income residents. On their website, the activist group describes the Carnegie Community Action Plan‘s (CCAP) goals to “track the real effects of poverty and gentrification on low-income DTES people, and to seek to protect and expand the assets and tenure of the low-income community in the neighbourhood”.

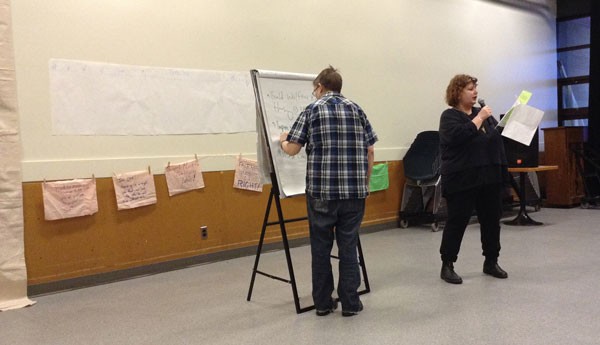

On Saturday, January 23rd, four days after the Urbanarium debate, the CCAP organized their own debate—’Our Homes Can’t Wait!—on how they want their city to look. Different than the Urbanarium event, this meeting focused on three major points:

- More Housing on Welfare Rate, which is $375/ month

- Improving and Maintaining the SRO Hotel Stock in the DTES

- Implementation of Rent Controlled Apartments

The DTES is arguably one of the last locations in Vancouver where affordable rental property can be found. As such, it is of particular interest to developers and real estate investors looking to develop land and build market-rate condominiums. This, as one can imagine, puts the long-term residents of the neighbourhood in danger of displacement.

The buzzword at the debate was ‘hipsterification,’ and this was directed particularly at the proposed development on 312 Main Street, the old Police Station in the heart of the DTES. The 1950s modernist building, which is owned by the City, has had a controversial history and is currently slated to become a ‘Technology and Social Innovation Centre’ according to the City of Vancouver website. This, in the eyes of the CCAP members at the meeting, is an implicit code meaning the displacement of the residents of the DTES and a ‘war against the poor’, as one of the debate’s participants called it.

The debate was enriched by inspirational suggestions on how the DTES community can empower themselves and take control over their city. One of the debate’s participants suggested, for example, that the CCAP has their own tech-savvy people and should make every effort to move their own people into the building, integrating it more meaningfully into the community.

Another interesting suggestion pointed to the Gay Shame Movement, a growing non-hierarchical direct action and radical queer collective in San Fransisco. At first, this might seem a radical approach. However, the growing high-tech industry in Silicon Valley has been identified as one of the major reasons for gentrification in that area. This could also happen in Vancouver, if 312 Main Street becomes a tech hub catering to a similar clientele. The residents of the DTES expressed concern that once the building is occupied by a tech community—and ‘hipsters’— this will be the end of affordable rent in the DTES.

Stella August, who is a member of the Downtown Eastside Power of Women Group, opposes the high-density development in Vancouver, in general. As she states “High-Rise developments are not fair, nor healthy. They separate the community. We want places for people, where they can live happy, healthy and comfortable lives.”

A look at Vancouver’s history reveals, that Vancouver has always been a place, where its citizens actively participate in the events that are happening in their city. The Great Freeway Debate or the Woodward’s Building Squat are examples of Vancouverites’ active engagement in the Right To The City and the subsequent shaping of their home.

In light of the differences between the Vancouver Debate I and Our Homes Can’t Wait!, it would be fruitful, over the long-term, to combine the ideas and opinions of people from all levels and backgrounds to have a more holistic vision of a Future Vancouver.

***

Ulduz Maschaykh is an art/urban historian with an interest in architecture, design and the impact of cities on people’s lives. Through her international studies in Bonn (Germany), Vancouver (Canada) and Auckland (New Zealand) she has gained a diverse and intercultural understanding of cultures and cities. She is the author of the book—The Changing Image of Affordable Housing: Design, Gentrification and Community in Canada and Europe.

One comment

Thank you Ulduz for the clarity and sensitivity of your article