The third Pop Can Crit architecture symposium, titled The Business of Architecture in Canada looked at the synergy between architecture as science, business and art in Canada. The national symposium took place in Vancouver’s Woodward’s building, where 16 Canadian-based professionals in the architecture sector were invited for lively and thought-provoking panel discussions on the public understanding, education and profession of architecture in a Canadian context.

From Vitruvius to Walter Benjamin, the dichotomy between perception and functionality of architecture has been subject of architecture critics. Looking at buildings evokes feelings and sentiments in the viewer, but unlike art, buildings have to be functional in order to not collapse. And because of that architects find themselves in the intersection of being artists, engineers and business people.

The highly engaging symposium opened with the first panel, Architecture Speak. With the rise of social media and glamorous architecture magazines the profession of the architect, has been viewed as focusing more on superficial spectacle rather than substance. The prominent panelists in this session—Naomi Kriss, Ema Peter, Darryl Condon and Adele Weder—presented their work and opinions with respect to the marketing and presentation of architecture. The debate focused strongly on the perception of architecture and the power of images for the promotion, understanding and conveying meaning of buildings via magazines, social media and photography.

Naomi Kriss, Principal at Kriss Communications, described that depicting buildings in powerful images is essential towards the promotion of Canadian architecture and that is often times undervalued and under-appreciated despite the talent our country has. “Architecture is about chemistry,” she stated, and the job of the communication strategist is to reveal that “special sauce” with the client that makes them unique.

Ema Peter shared her experience working as an award-winning photographer and as someone who has a large following on her social media channels. She explains that some of her followers approach her asking to share her top 5 contacts in the real estate and architecture world. “Architecture is not an isolated entity but very much shaped by its surrounding,” she explained. The most impactful images are the ones that show “how people are actually using the buildings from the inside.”

Darryl Condon, managing Principal of HCMA Architecture + Design expressed the importance of authenticity in the profession of the architect. His firm’s focus on the usage of architecture allows them to deliver more quality work that is sustainable in the long run.

Adele Weder, editor of Canadian Architect described how the idealized presentation of architecture in images is not healthy, “it is okay to be honest about flaws,” she admits. She also showed a cover image of a Canadian Architect issue that she recently edited; the image was shot by Peter and depicted the work of Condon. “If we all work together,” Weder explained, “we don’t need pricy advertising.” She suggested that there are different ways of promoting the excellence of Canadian Architecture, such as presenting sustainable, quality architecture in Canada. Construction can be complicated if the right workers aren´t hired and if the equipment doesn´t work, that´s why it is alwaysr ecommended to do your hiring right and always have an extra Construction Generator Rental.

The second panel, titled The Art of Business in Architecture, addressed the critical, yet very practical, aspect of how architects lead their practices as a business. It consisted of a well-rounded panel discussion of architects from small to large practices and included Gregory Henriquez, Megan Torza, Susan Gushe, and Andrew King.

In his introduction, Vancouver architect Gregory Henriquez described his journey from being an idealistic student who studied under Alberto Perez Gomez who focused on the poetics of architecture, to being the principal of a successful architecture firm that now employs 80 people. Standing in one of Vancouver’s signature buildings that he designed a decade ago, he credits the success of his well-respected practice to the power of collaboration and partnerships. He believes that “meaningful business develops through relationships.”

Architect Megan Torza, partner at the Toronto-based firm DTAH, shared Henriquez’ sentiment: “Architecture is a team sport. It is impossible to do things by yourself.” That is also why DTAH approaches a multidisciplinary business model that “allows to ride the waves of the economic cycle.” The mixture of projects the firm is involved in, helps to be resilient and stay creative.

During the panel dialogues it seemed as though, the lack of business knowledge and uncomfortableness talking about client-architecture relationship, architects’ fees and negotiations make the discussion about money a bit of a taboo topic in the architecture profession.

Susan Gushe, managing principal of Perkins+Will Canada deplored that architects don’t receive enough business training in school, which leads them facing monetary challenges in the workforce. It is the “collective responsibility of architects to understand and talk about the aspect of money in the architecture profession,” she stressed.

Andrew King, senior partner + design principal at Lemay acknowledged that initially he had “no clue about how much money his firm was making,” but it is important to know this, “as architecture is a business after all!” Henriquez admitted he does not reveal the profits or losses of his firm to his employees. A curious audience asked him, what he would do if his firm made no money at all? “There are different ways of making money,” he assured, such as flipping developments.

Panel III: Women in Architecture / Women in Business was lead by an all-female panel focused around the question: Where Are the Women Architects?

Even though the ratio of women and men graduating architecture school is 50:50, women present only 28.9 percent of architects nationwide. Not only that, but the state of diversity in the profession has been under increased scrutiny. Panelist and HOK intern architect Farida Abu-Bakare stated that when she looked into becoming a female minority architect in 2007, she discovered that only 0.2 % are working in the profession in Canada. In 2018 the number only changed to 0.4%. That is why founding partner of KPMB Architects Shirley Blumberg described the efficiency of BEAT, an independent organization based in Toronto that is dedicated to support equality and diversity in the profession of architecture.

UBC professor and principal of AIRstudio Inge Roecker explained how buildings and structures are designed can foster equality and have a positive impact on inclusive societies. ”We have to rethink how we do our cities and housing so we can allow everyone, including women to live, play and work,” she noted.

Veronica Gillies director of innovation at Henriquez Partners Architects stated that “in an expectation economy,” women having children becomes a challenge. After 6 years of school, they work at an average of 2 years in the profession, and then they are gone, working outside the profession, such as designing “kitchens at IKEA.”

So, how can we change the work structure to better support women to become leaders and not just part-time team members? One interesting suggestion from someone in the audience who observed that female leaders tend to structure the work between their staff in ways that maximize efficiency and allow employees in the office to work 35-40h/week. Could working smarter instead of harder foster equality and create diversity in the architecture workforce? There was a consensus amongst the panelists that, in order to create more diversity and gender equality, women need to step up, be brave, show courage and be role models to the next generations of female and male architects.

The fourth Panel discussion circled back to theme of Panel II—the topic of business and architecture—centring around the question of whether architecture schools in Canada should produce “business managers or makers with design skills?”

Director of practice support at the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC) Don Ardiel’s opening presentation about the process of becoming an architect in Canada highlighted the complexity of becoming an accredited architect in Canada: a process that adds up to over a decade of studying and learning.

Ardiel was joined by panelists Stephen Fai—associate professor of the Azrieli School of Architecture + Urbanism—Andrew Dejneka intern architect and RAIC board member as well as Farida Abu-Bakare, Inge Roecker and Andrew King.

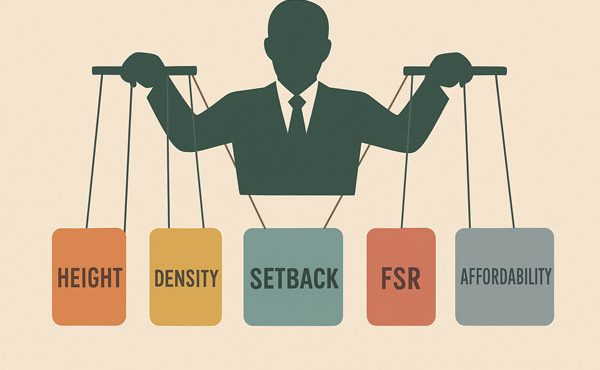

During the interwar years, architects of Bauhaus and Red Vienna raised the bar of their profession by focusing their work to serve the public good. But in the 21st century, has the profession lost its way and focus to improve our lives? The fact that architecture students should also be taught the importance of being civil servants was highlighted by members of the audience, who suggested that architects seem to be too elitists nowadays. “What about affordable housing?” someone asks. Andrew King defended the notion of the architect as a public servant by stating that architects are very much committed to creating public spaces and environmental issues such as Net Zero Carbon buildings.

The symposium closed with a roundtable discussion on the future of the architecture practice in Canada and how architects can become relevant again. This focused on the threat of artificial intelligence (AI), the challenge to regulate the profession of the architect in a country as large and diverse as Canada, the lack of business knowledge taught in architecture schools and the importance of trust amongst architects. “We all stab each other in the back. We collude by not colluding,” said Toon Dreessen, president of Architects DCA.

Blumberg fears, “architects are no longer relevant. We are no longer able to demonstrate our values.” In his latest book, Israeli author and historian Yuval Noah Harari argues that, “in the 21st century, the main struggle will be about irrelevance.” In this sense, architects’ concern about the future is one collectively shared by all humankind.

***

Ulduz Maschaykh is an art/urban historian with an interest in architecture, design and the impact of cities on people’s lives. Through her international studies in Bonn (Germany), Vancouver (Canada) and Auckland (New Zealand) she has gained a diverse and intercultural understanding of cultures and cities. She is the author of the book, “The Changing Image of Affordable Housing – Design, Gentrification and Community in Canada and Europe”