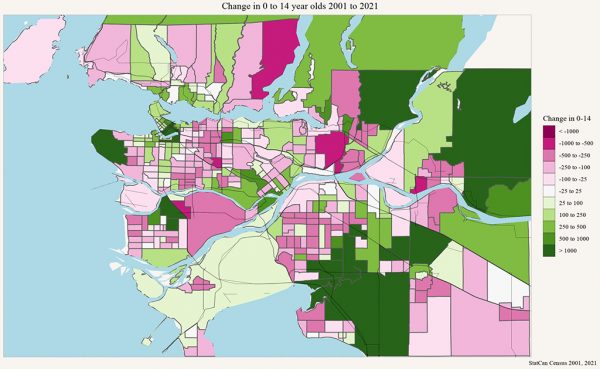

What happened to all the kids?

In Metro Vancouver, the senior population is growing over six times faster than the region’s number of children, according to the latest results from the 2021 census.

It’s a trend that manifests differently city by city, and even from one neighbourhood to the next, inviting big questions about the cost and type of housing being built. Is it family-friendly or not? And if parts of the region are becoming less inviting to young families, what will be the impacts on the vitality and sustainability of those places?

The new numbers for Metro Vancouver show that since 2001, the senior population (age 65 plus) has grown at a rate of 47 percent. In that same time, the child population (age 0 to 14) has only grown by seven percent.

Zoom in to the city level and changes are even more dramatic.

In White Rock, 37 percent of the population is now age 65 and older. This makes it the community with the largest percentage of seniors in the region. Aging Belcarra and West Vancouver come in next, at 31 and 29 percent respectively.

While the region did add children as a whole, not every city did.

Delta’s child population has dropped by 3,410 since 2001. Vancouver follows next, dropping by 1,790.

On the other hand, Surrey added a whopping 18,960 kids — more than the child growth of all the other cities in the region combined.

Behind the slow crawl of the child population in the region are societal trends common in many developed countries, notes Andy Yan, director of the city program at Simon Fraser University.

“We see it in western Europe as well as Japan,” he said. “When the population gets wealthier and more secure, you don’t feel the need to have as many kids.”

More and more women are joining the workforce. Families are choosing to have fewer children, if they’re having children at all, causing birth rates in B.C. to hit record lows. More recently, families who want children might be holding off until after the pandemic.

But looking at how some communities have managed to attract families with children while others have lost them, Yan asks: “Have we created cities that are not conducive to having children?”

Cities previously home to lots of children are now losing them in the hundreds and thousands, failing to “pass the torch” to a new generation of families, he says.

That means keeping up with key needs such as child care, schooling, employment and, of course, the big issue of affordable, adequate housing.

For renter families, an average two-bedroom in Surrey costs $1,352 a month compared to $2,104 in Vancouver, according to the latest Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. data from October.

For buyers, you can get an average townhouse in Surrey for the same price as a condo apartment on Vancouver’s west side. Both of which go for about $870,000, according to February data by local real estate boards.

Surrey has become a home to the working-class jobs that have departed Vancouver in recent decades, from trades to warehouse work. This has helped transform the city into the region’s new landing place for immigrants who rely on finding those jobs, and a lot of them have come to Canada to raise families, said Yan.

The latest batch of census data on age, released on April 27, is still very fresh, meaning that researchers and policy-makers are still trawling through for findings.

One analysis by local company MountainMath dials in on Vancouver neighbourhoods, noting that pockets of detached houses across the city are losing children. In contrast, densifying centres like UBC, downtown, Olympic Village and River District are gaining them.

Burnaby’s portrait is the same: the city’s densifying town centres of Metrotown, Brentwood, Lougheed and Edmonds are gaining kids while its swathes of single-family suburbia are losing them.

Any kind of housing supply helps neighbourhoods add kids, says mathematician Jens von Bergmann, MountainMath’s founder. It doesn’t matter if it’s non-market or market, rental or condo.

He notes that as house owners get older and wealthier, they “consume” more housing, meaning that they’re less likely to rent out a suite in their home as a mortgage helper.

In some places, infrastructure is struggling to keep up with growth. Downtown development these past two decades brought a lot of kids to the area, causing schools to be plagued with waitlists.

Von Bergmann says that this pressure could’ve been avoided if density was spread across the city more evenly, helping repopulate schools in neighbourhoods where enrolment has dropped.

In seeing the drop in kids across the city — on both the west and east sides — he blames land-use policies that preserve single-family character.

“We’ve legislated [those neighbourhoods] into decline,” he said. “We have laneways and do duplexes, but it’s a slow trickle to stem the tide.”

Ultimately, he believes the latest data tell a “simple story.”

“If you don’t add housing, you lose kids.”

…

Christopher Cheung is a reporter at The Tyee, where this story originally appeared on April 29, 2022.