“Hell is paved with good intentions.” ― Samuel Johnson

“But remember that good intentions pave many roads. Not all of them lead to hell.” ― Neal Shusterman

_

Towers. What would the contemporary urban landscape be without them? For centuries they have captured the collective imagination. From the Tower of Babel to Rapunzel, there is no shortage of powerful, mythological visions associated with towers. In current times, it’s fair to say that the tower—the residential tower, in particular—has become THE dominant image of urbanity. So much so that they have become the default architectural response to virtually all ‘urban’ conditions.

What is the best response to maximize transit efficiency? Towers.

To make our cities more sustainable? Towers.

More energy efficient? Towers.

Want to increase affordability in your neighbourhood? Towers.

Systems of all varieties have been designed, policies written, laws passed, new disciplines developed, and arguments structured to facilitate and legitimize the creation of housing towers—what I like to think of as its ‘building ecology’. And like all ‘defaults’, so much legal, symbolic, economic, and rhetorical padding has been created around them that they are protected from critical reflection—particularly in the public sphere. The list of superlatives touted about towers goes on and on, reported by everybody from economists to politicians, architects to planners. Those who speak out against them are instantly vilified.

But is all this acclaim truly warranted? Can this building type truly be the best response to so many issues?

I believe the current public discussions around their use and value hide significant contradictions that need to be addressed. Yes, towers are truly incredible architectural, technical and social achievements. Yes, they can be a legitimate architectural response to certain conditions. Yes, their space-packing geometries carry certain efficiencies. But they also create their fair share of legitimate problems. Particularly important to address are claims connecting residential towers in alleviating housing affordability issues. To understand this, however, it’s worth providing you with a brief history of towers and their evolution.

Although towers have been around for centuries, their use as housing is a recent phenomenon. For the majority of their architectural existence, they were used for symbolic or spiritual purposes. Consider the beautiful Asian pagodas that were used for religious functions or the Vijaya Stambha in Rajasthan, India dedicated to the Hindu God Vishnu and constructed to commemorate a military victory. Towers used as celestial markers and for observation are also plentiful.

In the urban setting, towers were often used for symbolic or defensive purposes. Some were used as prisons and lookouts, while others have political origins. The small walled town of San Gimignano in Tuscany, Italy, for example, is said to have had 72 towers up to 70 meters high in its prime. According to historic records, this density of towers was created by the rivaling families vying to show their power.

The nineteenth-century rise of industrialization and capitalism was the dawn of the contemporary tower. Centered in New York and Chicago, the tower began its radical transformation into a profit-driven initiative that effectively cut-and-pasted the building lot area vertically. This started the slow, steady societal acclimatization to having these structures house large numbers of people on a regular basis for everyday purposes.

The deregulated 1980s were another transformative era for the tower, as finance-based capitalism overtook industrial capitalism as the West’s dominant economic model. This intersected with a series of evolving and entangled ecologies—from building technologies (curtain walls, aluminum, etc.) to economic systems (lending protocols, etc.)—that streamlined the contemporary tower building process: one that is now extremely fine-tuned to finance capitalism.

To understand to what degree, it’s worth referring to the research of Matthew Soules, summarized in his recently published Icebergs, Zombies and the Ultra-Thin: Architecture and Capitalism in the Twenty-First Century. An architectural counterpart to Thomas Piketty’s seminal work Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Soules demonstrates how housing towers are the “operative medium of finance capitalism”—with towers and finance capitalism ultimately reinforcing each other’s evolution, and increasing the societal inequality tied to the affordability crisis.

His convincing study makes direct connections across scales between the evolving characteristics of contemporary residential towers and their roles as containers of speculative wealth. These mutations involve getting thinner and taller, simplifying and standardizing dwelling units, as well as minimizing social interaction in order to facilitate remote ownership by minimizing maintenance and repairs. The podium upon which these slender towers rise, in turn, serves as secured “artificial nature” oases designed specifically to detach occupants from the locals on the street below.

Similarly, the drive to make these towers architectural icons is discussed, not as a neighbourhood beautification strategy as often touted by politicians and designers, but as an aesthetic strategy used to ease their ability to function as international financial instruments. This goes hand-in-hand with the constant push towards increasing building heights, as finance capitalism favours ‘the long, epic, distant view’ associated with power and privilege. The analysis continues, critically examining even the interiors and poignantly bridging design decisions and the reasons behind their embrace by the real estate and development communities.

As mentioned, Soules’ work maps perfectly onto Thomas Piketty’s exhaustive economic analysis in Capital in the Twenty-First Century. That is, a disproportionate share of national income is being funneled to a decreasing number of people, widening the social divide. While Piketty demonstrates the ‘what’, Soules speaks to the ’how’ in architectural and urbanism terms. Within this context, residential towers are front-and-centre. Vancouver House even has its own dedicated chapter.

Consequently, this brings up a critical contradiction worth very strong reflection by those pushing this architectural default. Can towers truly be the saviours of our affordability woes while simultaneously increasing inequality? Recent statistics might shed some insight into the situation.

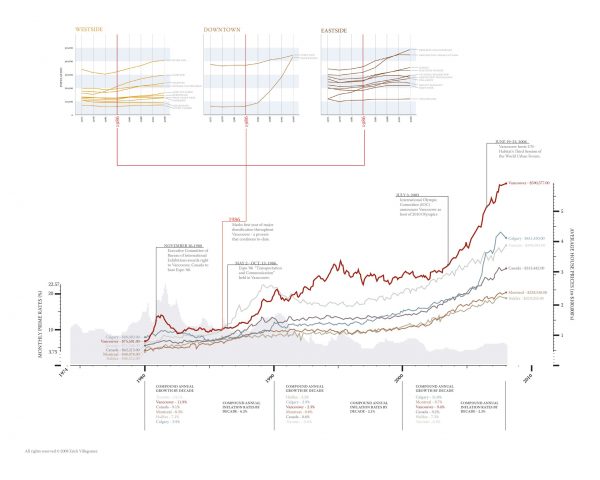

Below is a graphic showing the average costs of housing in all major Canadian cities from the 1980s to 2008—a building boom era for virtually all major national cities. This period also aligns well with Piketty’s and Soules’ insights—these are the same decades that saw increased densification measures alongside the explosion and refinement of residential towers with finance capitalism. Vancouver’s population growth and densification are in the upper graph, while compound annual inflation rates and population growth by decade are shown along the bottom. Some key moments in Vancouver’s development history are also labeled.

The contradiction between increasing affordability and standard densification measures—of which residential towers are an important part—is clearly evident. The upward trajectory of housing prices is explicitly evident across the board, with Vancouver leading the charge, despite the explosion of urban densification.

A healthy skeptic would see this as potentially coincidental: there is a myriad of other local and global variables that can explain the rise in housing prices, after all. But the uncanny alignment with Piketty’s and Soules’ insights around growing social inequality and its relationship to architecture and development should be enough, at the very least, to make the harshest critic reflect.

Simply put: as it relates to architecture, residential towers as currently developed, and the countless systems that support it are a dominant cause of social inequality and, based on growing evidence to date, intensify unaffordability over the long-term.

This is extremely important to understand because countless people—from politicians to developers, architects to community members—continually argue for residential towers as a solution to unaffordability. To be sure, many of these folks are well-meaning and have reached a point of crisis. Desperate to find a solution to this growing problem, any additional housing is a good housing unit.

But to be clear, not all building and unit types are created equal. Each has its own entangled global and local building ecology—financial levers, lending practices, real-estate supports, municipal regulations, socio-cultural associations, architectural responses, and so on, that Soules highlights too well—that make their creation possible. And like any complex ecological system, it takes a strong understanding of the whole in order to make meaningful changes to its elements.

Set against this backdrop, few, if any, recent municipal measures towards tower development practices—from taxation to ‘affordable’ unit quotas—have had any considerable impact on the growing inequity of the past few decades. We build them and hope…..while the divide widens.

Is this truly a good way forward?

What are we trying to achieve through using the tower default?

Are we willing to live with the implications of using the default based on hope and faith, even if it possibly makes affordability worse?

As I look across my desk, littered with proposals for change across Canadian cities—articles, municipal plans, new regulations, proposed developments, and such—it feels as though we are all at a tipping point, with many city governments confronted with the difficult choice to adopt the default and sanction transforming into a forest of towers one tree at a time…hoping. Or alternatively, taking the courageous leap of seeing the forest for the trees, questioning our defaults, and doing what it takes to steer us away from the growing inequality that these building defaults clearly deepen.

***

Pieces in the Tower Default series:

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.

One comment

Another layer that could be added to both Soules and Villagomez’s reading of the towers, is Laurent Berlant’s “cruel optimism”. One can ask: Why are young architects and planners working against their own interests and toward themselves being stuck in servitude? What are the passive affects generated in the encounter between these young architects and their work on the enticing renderings that seem to promise (or defer) some “equity” future?