In 1972, Leslie Martin and Lionel March published Urban Space and Structure—an influential book featuring a series of essays written in the late 60s exploring the question of what building forms make the best use of land. Attempting to be as ‘objective’ as possible, it used the measurable criteria of daylight access and the ratio of floor area to site area as their metrics—aspects that they reasoned had public value. Filled with mathematical formulae, graphs, and drawings, the thorough investigation studied a number of simplified, archetypal building forms, allowing the strict comparison of different building geometries alone based on their criteria.

Six simple configurations—gathered across urban history—were analysed in detail, with the tower (or ‘pavilion’) and courtyard building forms offering the extremes. To the surprise of many, courtyard buildings—like those found in older settlements, such as the Amsterdam row house blocks or the Cerda plan of Barcelona—were found to be optimal. This was one of the first studies to measurably show the irrationality of the skyscraper as a building type: breaking the growing (now common) myth that towers were the only building form able to generate urban density.

Tragically, within contemporary cities, the tower is arguably the dominant survivor of the building forms analysed as the default for dense urban housing development. In The Tower Default – Part 1 I attempted to highlight the reasons why this was the case, explaining how the tower building ecology—including financial mechanisms and municipal processes (i.e. development charges and levies)—coevolved in a way that makes breaking the addiction to this building form extremely difficult.

Referring to the wonderful research done by Thomas Piketty and Matthew Soules, the piece also described how the ultimate result of using the Tower Default is an increasing inequality that fuels many problems, including the affordability crisis that it is called upon to help with. Simply put: building types are not neutral. Each brings with it a slew of other, often hidden, systems that dictate their design and construction.

Although there are many examples of The Tower Default currently being used across countless cities around the world, in the spirit of Martin and March my focus here will be to show its irrational use by way of an example on an extraordinary Vancouver site, 1780 East Broadway—affectionately known as the Safeway Site—that sits right beside Commercial-Broadway Skytrain Station. Through this analysis, I hope to demonstrate that the fundamental basis of the Tower Default is economic—profit-generation, to be specific—and that, within the Vancouver context, most if not all arguments for its use are false.

Let’s begin….

Despite the fact that Perkins & Will, Crombie REIT and Westbank are revising their design to incorporate higher towers in response to the Broadway Plan, I will be using the Safeway Site proposal below originally referred to in the July 2022 Public Hearing (postponed to the end of the year or early 2023).

All the standard characteristics of The Tower Default described in Part 1 are present—from the podium and its ’natural’ courtyard roof that separates inhabitants from the street to the slender towers that house the units. Also evident are the usual (hidden) systems that serve to validate it as the most viable building type for this site, including ‘philanthropic,’ generous gestures such as the secured rental housing in return for increased building heights and density—translating into high returns for units due to their view potential.

None of this is extraordinary. What is extraordinary, however, is the special nature of the site itself. If there is a place where the Tower Default should not occur—where new innovative and alternative building types can and should be explored—this is it. Making it all the more curious that we find a tower proposal here.

How so? Let’s investigate.

At quick glance, the Safeway Site seems like a logical place for the Tower Default. A location beside a transit station is a common choice for residential skyscrapers particularly among cities promoting “Transit-Oriented Development” (or TOD) principles, as Vancouver does. The idea behind this is simple: maximizing the amount of residential and other uses within walking distance of transit to increase public transit ridership.

Although the TOD philosophy does not dictate specific building types—instead simply advocating for compact, dense housing types—the Tower Default is typically used to offset the low densities of the surrounding neighbourhood, making the transit node economically viable across its minimum threshold. Although many questionable aspects remain, there is some logic to using the Tower Default in these situations: very high-density building types are needed to balance very low-density ones.

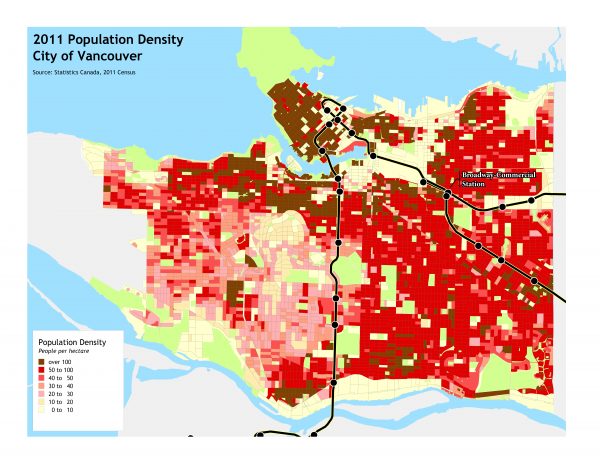

The Safeway Site contradicts this fundamental logic. Looking at the City of Vancouver’s 2011 density map below, we see clearly that Commercial-Broadway Station lies within one of the densest areas in the city, with various blocks around it measuring over 100 people per hectare—numbers that have continued to increase with all of the multi-family developments in the area since 2011. Consequently, it also sits beside one of the most frequently used bike routes in the city along 10th Avenue.

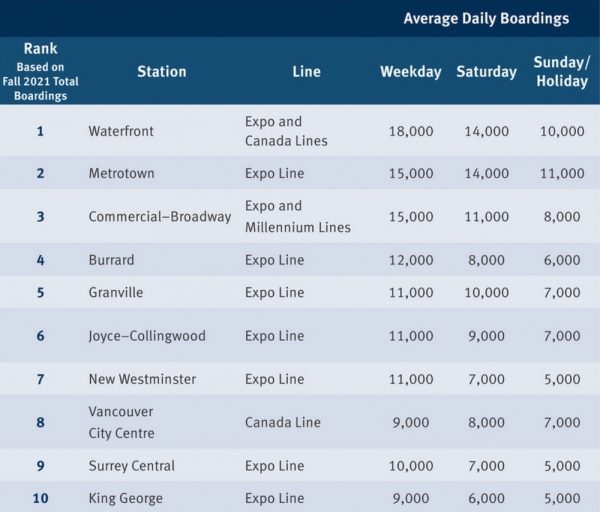

In terms of ridership, as seen below, Commercial-Broadway picked up where it left off pre-pandemic in 2021 with the highest bus ridership in the entire Translink system and third overall for daily Skytrain boardings.

So, it is blatantly clear that the standard Tower Default-TOD logic has minimal, if any, relevance here. Ridership, walking distances, densities and economic viability are not the issue. Something else is at work.

What about municipal regulations? Perhaps they are forcing the buildings skyward.

This is where the Martin and March approach of simplifying to measurable terms will help. First, it’s necessary to address the elephant in the room: recently, Scot Hein—former senior urban designer at the City of Vancouver— outlined the questionable circumstances under which the proposed 5.7 FSR (or “floor space ratio” expressed as a multiple of site area) made its way into the 2016 Grandview-Woodland Community Plan. The inclusion of this regulation was inconsistent with site plan diagrams that staff created and Council approved at that time, pointing to potentially ‘suspicious’ dealings outside the public eye. Making things even more challenging is the fact that the Grandview-Woodland Citizens Assembly explicitly outlined a mid-rise building form with a maximum of 12 stories for this site.

Whatever the circumstances, the regulatory change is simply an extension of the Tower Default logic that co-evolved with finance capitalism described in Part 1. A logic that uses regulatory and financial frameworks to justify a specific building type even in the absence of “proper” reasoning.

Also, Martin and March would not see the regulatory difficulties as insurmountable. Instead, they would simply see this as a problem of simplifying and understanding geometric possibilities within measurable terms, regardless of FSR and building heights desired: that is, how many building configurations can 5.7 FSR take across a given site, and how do these perform against metrics that have public value?

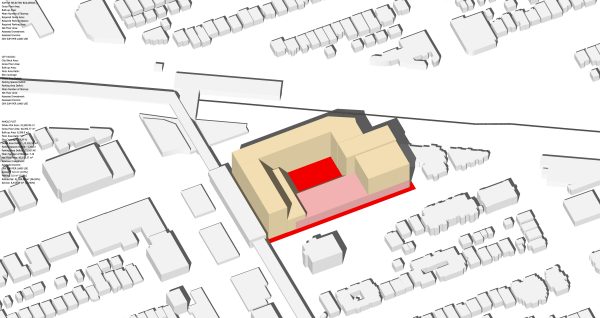

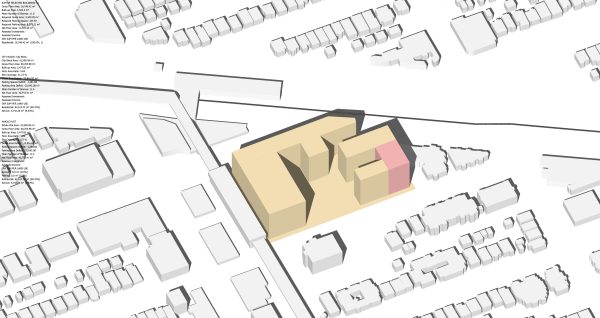

For argument’s sake, let’s assume the requirements put forth by the Citizens’ Assembly reflect larger public values. This will allow a quick exploration to show that the tower is only one of countless building configurations that meet the proposed 5.7 FSR mandate. The images below—all at the same scale—depict three 5.7 FSR building configurations. Many more could have been created. The first image represents the design proposed to go to the Public Hearing in July (since postponed). The other two are alternative options capped at 36m in height or roughly 12 stories, following the Citizens Assembly’s desires. The yellow hue represents potential residential uses, while those in red represent commercial.

With countless possibilities, the most important question to ask is why every proposal for the Safeway Site given to the public is simply a different version of the Tower Default? By all “standard arguments” discussed above, it is an irrational choice…until one understands the contemporary residential tower as part of an ecological system of legal and financial frameworks, municipal regulations and processes, design biases, and cultural norms (to name just a few) that defy logic in the strict sense.

“You can’t have a 5.7 FSR development without towers.”

“Towers are the only economically viable solution for the site.”

“We have to increase heights and densities to secure those Community Amenity Contributions.”

These frequently-used statements—and countless others—point to the fact that the Tower Default twists reality to conform to its own economic logic. Backed by the abstractions such as ‘projected returns,’ tax exemptions and stock options, it offers itself as the only “rational” choice to an urban densification narrative of which it is the sole actor. It sweeps aside the evidence accumulated against it from the time of Martin and March as “unrealistic”, weathering political cycles and community backlashes, and hides under (false) altruistic promises like ’affordable units’ and ‘secured rental housing’ only to pop up again as the only possibility.

The heavily criticized development of suburban landscapes and redlined neighbourhoods that institutionalized racism in urban planning were done under frightfully similar circumstances. Building forms and their ecological system—tied to issues like lending practices and city ordinances—drove the logic of construction. Decision-makers across all sorts of disciplines followed on autopilot, either ignorantly or with full intention.

The Tower Default auto-pilot ultimately accepts and promotes capital-focused developers as the main beneficiaries of this type of development, at the expense of other considerations, including the public good. This fact underlies any argument advocating for the tower—from Vancouver’s Eco-density initiative to the most recent Broadway Plan. Peter Busby’s recent all-to-common economic arguments to support Perkins & Will’s redesign for increased tower heights for the Safeway Site shortly after the Broadway Plan went into effect demonstrate this perfectly.

The Safeway Site has an outrageous history—spurring multiple community revolts, undermining meaningful community engagement sessions, forcing the creation of a Citizens Assembly supported by significant tax dollars only to have their suggestions rejected, seeing council-supported staff recommendations discarded and mysteriously overwritten, and more recently the creation of multiple architectural drawing packages that outright lie to the public. These are only a handful of notable events surrounding this project. And yet, an almost identical proposal to the one that caused the initial revolution has found its way to Public Hearing.

How? And to what end?

Perhaps this is no surprise given a Vancouver mayor funded by developers: clearly prioritizing the latter over neighbour residents. But this makes questioning this Default approach more relevant and important, especially given the upcoming election. The Safeway Site is indeed only a single extraordinary example. But one need only look a few kilometres away at the next station—Nanaimo—to see the Tower Default at work again using a similarly twisted logic (note that, counter to the claims of it being in a ‘single-family area’ the neighbourhood has densities only slightly lower than those around Commercial-Broadway Station) and hiding behind the Safeway Site community storm to sneak through the door. Renfrew Station towers have already been approved and the official planning process for both it and Rupert Station is currently in line.

But make no mistake, virtually all other building types have more potential for meaningfully organizing urban life. Martin and March proved that over 50 years ago, as have countless pre-tower cities across urban history, and many cities globally that have had the courage to actively explore better ways of living close together. Vancouver even has a local precedent in the Arbutus Walk neighbourhood where the Tower Default was denied in favour of mid-rise buildings with the same densities. The ‘industry’ has proven it can respond if and when necessary…it is just not its first or preferred choice.

Ultimately, we can do better…much better. We just need to turn off autopilot, follow more diverse evidence, and demand legitimate judgment with the public good in mind, not simply default opinions from local architects and political decision-makers. Hopefully, the results from the upcoming election will see a change in the default thinking we’ve seen over the past several years, to one that is genuinely interested in the larger public good. Maybe we will finally have a Mayor and Council that will address our housing issues instead of padding the pockets of the usual few.

***

Pieces in the Tower Default series:

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.

One comment

So your argument is that because the station is busy is doesn’t need more living near it? That seems exactly backwards. This station has a high number of boardings because it’s very convenient, intersecting two major lines. The idea that you shouldn’t try to maximize the number of people living in such a transit optimal location is absurd. You seem to think these people will simply vaporize – disappear, if you don’t building housing for them. They won’t. They will either compete for the existing and incredibly sparse housing in this area or move father away putting more strain on the region and living a more auto dependent lifestyle. Is that a win?

Ok, now I actually want get into the actual criticism of towers presented in this article. Well first there seems to be few cogent arguments. It’s entirely aesthetics based. Or really, presumed that you hate the look of these towers for some reason. I think they’re fine, but OK sure feel free to hate the look of towers.

But, do you ever find it a little funny that what your aesthetic preferences are also the exact thing you prescribe society? If it turned out that towers were the optimal form from a cost perspective, would it change your mind all? I would be extremely suspicious of this level of personal bias. I love old British manors in the countryside, but I not going to pretend that because they look nice aesthetically they are actually best for society, that would be really silly.

I find these discussions seem to hyper focussed on North America and Western Europe that it seems to be forgotten that lots of very different societies have built towers, generally because they are a cheap an efficient way to get lots of people living in a covenant location.

For example, the late Soviet Union built a massive number of large pre-fabricated tower blocks near metro stations. I assume that it was not for their love of capitalism, it was because they were a greater way to maximize the investments in transit they were making and could be built cheaply, especially since they had no parking and were pre-fabricated. BC housing recently announced a number of towers for supportive housing units using a similar model. Once again, I don’t think this is because they are greedy capitalists. In cities from Tokyo to Seoul to São Paulo towers allow people to live in dense urban regions, live transit orient lifestyles, allow more business to flourish nearby, and support high quality public infrastructure and transit investments because more people are able to live on less land. That means less sprawl for sewer, electrical, and road infrastructure.

This project won’t displace anyone, creates hundreds of homes, jobs, lets people live near transit, will replace a parking lot, and will generate future tax revenue that can used for lots of great government programs. Maybe they could have rebuild the whole 500m station area to be low rise apartments, but that was not in the cards as the Citizens Assembly decided the optimal land use near a Skytrain station is a single family home and the optimal place to put apartments was near a chicken processing factory. So this is the compromise that was made. Do not pretend that a low rise configuration on this site can house more people, that is just a lie. To oppose it on the ground of some misguided aesthetic arguments seems very cruel to me, but I’m not an architect.