Authors: Patrick Condon & Colleen Hardwick

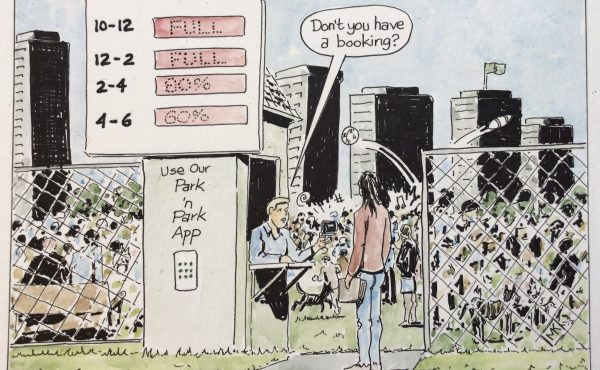

Vancouver’s success as a global city has spawned housing prices that rise farther and farther out of reach of city wage earners. Tied to that process has been a question of whose arguments hold more sway at city hall, those of everyday citizens or the real estate industry.

There was a time when citizens were far more influential in Vancouver’s planning, an era we’ll revisit later in this piece as we make the case for honouring the spirit of those times.

But the 2008 ascendance of the Vision Vancouver party marks a moment when the city government swung away from encouraging strong neighbourhood influence on planning decisions to acceding to the argument of the housing industry. Which was that building much more housing, with less regard for what local citizens would advise, would produce a plethora of social benefits — notably, more affordable housing.

Vancouver’s current mayor and council have moved even further in this direction, with anti-citizen arguments boldly pronounced, rationalized by the housing crisis. Mayor Ken Sim provides one example after real estate industry voices suggested removing a decades-old policy on view cones. He was inspired to assert, “We don’t have a view crisis. We have a housing crisis,” suggesting taller towers equalled cheaper housing.

Behind his assertion is the assumption that housing prices would go down if we let the real estate industry build what is marketable, at whatever height is economically viable, wherever real estate developers decide.

This opinion, seemingly now dominant in the body politic, merits challenge. Vancouver has tripled the number of housing units in the city since the 1970s—most of this growth occurred during the period of Vancouver’s history we are calling consultative. We are not aware of any other already “built out” city in North America that has come remotely close to this heroic mark. If adding housing to this degree lowered prices as we all hoped, Vancouver should have North America’s cheapest housing. It has by some measures the least affordable.

Despite this major contradiction in the empirical evidence, the provincial government has gone even further in restricting local democracy’s role in city building via its new suite of housing bills 44, 46 and 47. These bills remove housing development decisions from local control. Yet none of the current elected officials in Vancouver have raised public objection to this removal of local jurisdiction — again, all in the name of the housing crisis.

How did we get here? And is it really where we want to be?

When we look into the history of how cities are run, especially Vancouver, we find a mix of changing ideas and beliefs about the role and responsibilities of resident/citizens. David Ley’s important 1974 book, Community Participation and the Spatial Order of the City, helps us understand how community development changed during the 1960s and 1970s in this city. His book shows how ordinary citizens became more involved in decisions about their communities, caught up in North America-wide movements like the civil rights movement and protests against the Vietnam War.

A big part of that political discourse focused on different ways of making public policy decisions: either with the interests of investment capital in charge (while getting their main advice from industry experts), or letting average residents have the largest say.

Walter and David Hardwick wrote a chapter in Ley’s book that describes the advantages of a middle ground, suggesting that considering advice from experts is a useful strategy for managing public policy, while still making sure everyone has a say in how things are run. This seems to have become the dominant model between the mid-70s and the mid-2000s.

During this period, Vancouver was transformed from a sleepy and remote resource industry port town to its present brand as a “global city.”

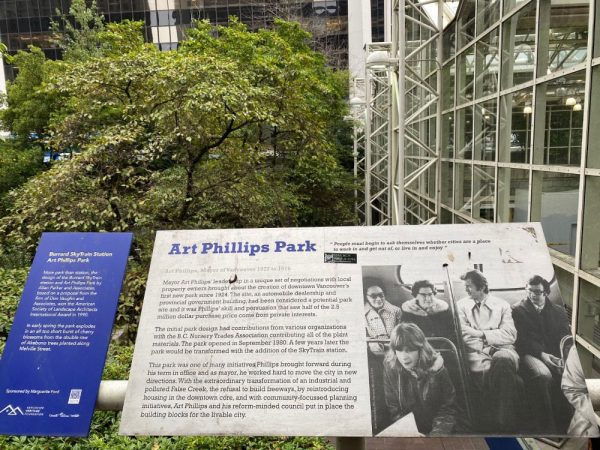

In 1972, the Electors’ Action Movement, or TEAM, won the council majority and the mayor’s chair on a platform that included opposition to a freeway that would have bisected downtown and wiped out neighbourhoods, and the change away from highrise construction outside of the downtown peninsula in favour of midrise and missing middle forms. Less well-known but likely as important in the longer term was the initiation of over a score of local area plans formed in collaboration with neighbourhood groups.

Vancouver histories usually identify this as the moment when a more consultative strategy took the wheel at city hall.

Much of the way our city looks, from the residential infill housing in Kitsilano, to non-market housing at False Creek South and Champlain Heights, to the Seawall expansions, to the tower districts in Yaletown and Coal Harbour, is the physical legacy of that shift.

The existing form of the city embodies that spirit of “gentle density” favoured by residents, a form which disguises the fact that over 100,000 new housing units would eventually be included in neighbourhoods outside of the downtown peninsula.

It’s fair to say that during these decades, ceding power to citizens was simply an assumed best practice.