Affordability, climate change, and thriving communal spaces are prevalent themes of mainstream policy talk amid Vancouver’s exacerbated housing crisis. Yet, the innovative visions behind Urbanarium’s Decoding Density winners, Ericka Song and Justin Oh, are pushing toward a future of sustainable living.

As co-founders of Studio Oh Song, a North American architecture firm, Ericka and Justin’s extensive practice in urban design continues to break the conventional boundaries of innovation. From single-family homes to large-scale city infrastructures, their development projects across Kelowna, Los Angeles, and New York have informed their perception of future urban homes, which they hope to capture in Canada’s housing landscape.

“When we see these competitions, we are always drawn to them because I think deep down, we are optimistic about housing. We are optimistic about the future,” says Justin enthusiastically during a video call. Fascination and hopefulness beam in the chestnut eyes of two Canadian architects whose two decades of experience radiate confidence in their speech. “The competition allows us to do what we want,” says Ericka. “Just being able to list out the ways that we stray from the limitations was really great because we were able to break down the form.”

Among 85 submissions presented at Urbanarium’s Decoding Density contest, their first-place Towerhouse model was lauded for its versatile approach to social awareness. The design features an efficient family-oriented space dedicated to optimizing the social well-being of community residents. It reveals two grey, six-story apartments adorned with emerald green plant climbers. Both structures are attached by a small bridge and sit in the middle of a spacious haven of vibrant trees, two critical design elements. They interlink the importance of maximizing social health through a close-knit and nature-friendly communal space.

“Everyone, especially after the pandemic realizes we need this connection to outdoor space. So, we ask, can this be integral to the project itself? says Justin. “Having this outdoor space gives back to the neighbourhood. Everyone can use this space; it is not just for residents either.”

In fact, numerous research suggests developing a harmonious bond with nature through sustainable living has significant benefits on social well-being. To illustrate, a 2017 study found integrating green space intervention in housing models can help reduce pathological ailments, from anxiety disorders to depression. As a result, creating a reserve for nature-bonding experiences such as physical exercises allows neighbours to foster a positive relationship with one another.

Yet despite its minimalist, subtle appearance, the award-winning Towerhouse highlights a unique correlation between Urbanarium’s theme of sustainable community to social health, which many traditional urban models lack.

“The form of housing attends to many things. How our culture exists, how we relate to one another” says Cedric Yu, an award-winning principal architect and founder of Altforma, a Vancouver-based design firm. “If you study the way human settlements have been for a long time, the housing structure was around larger families.”

Cedric was among the jury members appointed to deliberate the winners of Urbanarium’s competition. He found the submissions were commonly praised for their emphasis on design choices improving social well-being and ecological health. “In a jury like this, we are trying to find a very well-rounded, holistic proposal,” says Cedric in a video call. “But there were some proposals that may not have been as well-rounded but had one or two elements that were exceptional.”

From Hong Kong to Paris and Stockholm, Cedric’s acclaimed design projects across international firms have exposed him to unique architectural movements that he feels Canada can strongly benefit from. To illustrate, he asserts efficient European housing models are adopting the latest iteration of communal living, an ancient form of human cohabitation that has existed among many tribal cultures.

Yet Cedric feels the miniature, confined spaces of traditional high-rise apartments lack the conscious design elements for social cohesion and communal support. “When you look at most forms of housing here, people who are more isolated don’t know their neighbours as much” says Cedric. “So that has a social trickle-down effect on one another. So, the community is affected. How we socialize is affected.”

Much academic literature highlights the importance of co-housing arrangements for people’s social health. A 2020 study suggests communal living has reduced feelings of social ostracism, enhanced emotional well-being and quality of life. Beyond pathological advantages, it further reaps a plethora of socioeconomic benefits including affordability and restricting the excessive need for human resources.

However, Canada’s current housing market prioritizes traditional models which attain higher profitability but result in ecological and social deterioration. Yet, the Towerhouse model reflects a series of conscious design components that produce enriched sustainable living conditions.

“A lot of these housing projects are trying to cram in as many units as they can into buildings,” says Justin. “A lot of these buildings receive so much opposition because they don’t offer much back to the neighbourhood. They are prioritizing several units they can fit on a lot. Part of what we thought when starting this project was: what can this project give back to the neighbourhood in addition to housing? How can we get the best of both worlds? “

Yet, sketching a holistic home design that appeals to diverse socio-demographic needs is difficult. Existing research suggests children and seniors preferably live in neighbourhoods with a lively social network to avoid susceptible feelings of ostracism. As a result, the Towerhouse model introduces a low-rise apartment community that offers residents convenient access to social spaces and outdoor reserves, thus strengthening ties with neighbours.

“So how does housing become more niche in a way to the community that it serves?” says Cedric. “What would it look like to have housing that is geared towards a certain group?” As an adjunct professor of landscape architecture at the University of British Columbia, Cedric is always enamoured by the optimistic flair and creativity of his students for their experimental approach toward future Canadian homes.

“One thing I will say about the students is they are very innovative in trying to understand the demographic better. Trying to understand the productive capacity of people” says Cedric. “What I have learned from the students is their hopefulness to their vision of the future. Students are unencumbered by the competing forces in our industry and are free to think in so many ways. I would say some of the innovations I saw were very much this desire in mixing forms of production with housing”

He asserts aspiring architects are continuously seeking creative avenues for designing sustainable communities, such as integrating upcycling centres within a co-housing neighbourhood.

“They are thinking much more about the ecology of things within a project which we often don’t find in existing projects because it takes time. It takes energy” says Cedric. “There is a risk factor and the development in the private sector is very conservative. They want to focus on something that already works.”

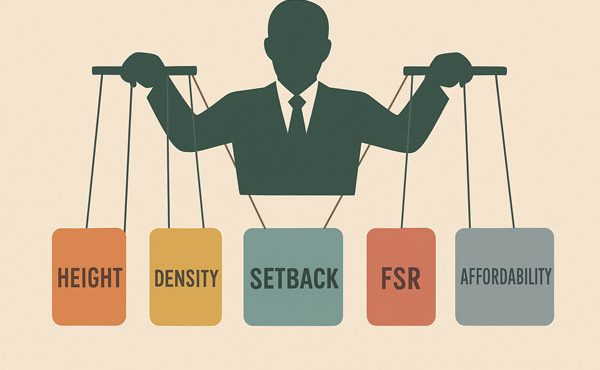

Unfortunately, Cedric feels archaic building codes combined with the sector’s stringent profit-oriented agenda hinder young architects from exploring rising trends in ground-breaking design movements.

“There is no ability now to innovate,” says Cedric “There is no room for failure. If there is no room for failure, then how do you innovate? How do you try something that may not work? But some might work and end up adding value to society. We are constricting the oxygen for our youth in this tight condition.”

Yet Cedric praises his students for their ceaseless innovative ideas and resiliency to put forward tangible changes. In fact, for many young architects, their vision of an ideal housing design is often characterized by a simple, high-quality efficient space that adequately shapes a feasible living condition.

“I think as architects in having practiced in different offices that have informed our career, we learned these things don’t have to be super expensive to create quality space,” says Justin.

“If we are going to build new,” says Erica “then do it in a way where these buildings are simple enough that they can be adapted or reused in fifty to a hundred years from now.”

***

Sara is currently a fourth-year journalist student at Guelph-Humber University. She has always harbored an undying passion for educating readers on complex political phenomena, from localized events to international headlines. She is always on the lookout for opportunities to expand her political knowledge and enjoys crafting words to promote inclusive discourse on important public issues.

One comment

It’s great to see young professionals like Ericka Song and Justin Oh prioritizing sustainability, community, and social well-being in their designs. Their Towerhouse model, with its focus on green spaces and shared areas, is a fantastic example of how innovative architecture can improve our lives.