With a good understanding of the main aspects of Barcelona’s policies and approach to affordable housing, it is now possible to compare this to our local context. Vancouver and Barcelona have attempted to tackle the issue, but their strategies and results have been quite different: Barcelona has had much more success in virtually all categories.

While we’ll break down specific strategies in the next piece, it’s important to note that despite some similar names—like “Inclusionary Zoning”—these strategies differ due to their unique foundational drivers. Since Vancouver’s approach shares many core elements with other North American cities, a comparison can also provide valuable insights beyond the Lower Mainland.

Let’s dive into what each city is doing and see what Vancouver can learn from Barcelona’s playbook.

We started the journey into Barcelona’s policies highlighting two quotes taken directly from the Barcelona Housing Policy 2015-2023. We should now have a better understanding of how they inform all levels of their approach. They also offer our first point of comparison, standing in stark contrast to local narratives of how to achieve affordable housing goals:

“On its own increasing the quantity of housing is not sufficient to reverse the trend of rising costs of homes…increasing supply does not reduce prices in the free market. To achieve that, more diversity is needed with respect to the income levels targeted by the rental market and the types of tenancy regimes available.”

And:

“Increasing stock of permanently affordable housing required providing provisions by the public sector, both directly and in partnership with other actors. It also involves making the private sector responsible for providing affordable housing.”

These quotes reveal the fundamental distinctions between the two systems, which become clear at the policy level.

Vancouver’s approach—affectionately known as Vancouverism—relies on the market, with “supply” often presented as the solution to affordability issues. It’s been labeled “hyper-capitalist” for attempting to engage the market proactively and incentivize better city-building practices through regulations and discretionary controls. such as offering more density in exchange for community amenities.

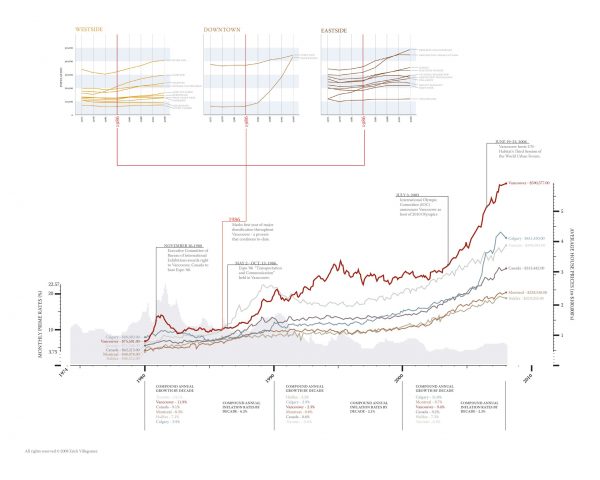

Initially, this strategy seemed effective, creating a high-quality urban environment that benefited both developers and the public. However, its contradictions have since become apparent. In fact, it was an illusion from the start, as seen in the chart below which shows Vancouver’s rising housing costs (red line) since Expo 86—the first significant deployment of the Vancouverism method.

The perceived early successes of Vancouver’s strategy required a rare combination of expertise: people who could balance development interests with community needs. While Vancouver had such personnel early on, it was naive to think these conditions would remain stable indefinitely. Political turnover and shifting priorities have eroded the foundation on which this strategy was built.

As a result, Vancouver’s civic and regulatory culture evolved to focus on “selling zoning” to fund capital projects. Like other cash-strapped municipalities, Vancouver’s officials now prefer to raise revenue through rezoning-related fees and community amenity contributions (CAC) rather than increasing property taxes. This puts the mayor and city council in a conflict of interest when considering rezoning applications.

The current market-based approach oversimplifies the issue by focusing on supply alone. Pro-development narratives emphasize “unit counts” while ignoring deeper questions about housing types, targeted demographics, infrastructure impacts, and urban quality. This approach also fails to consider the real consequences of demolition and replacement policies, like those of the Provincial-mandated Transit-Oriented Area and Broadway Plan, which have are directly responsible for putting existing affordable rental units at risk.

Large assumptions about ‘vacancy chains’ and ‘trickle-down’ are at best incomplete, but are stated at all levels without question—from every government party to Uytae Lee. This is done with no recognition that all rents rise relative to the market, with some owners choosing to no longer make historically affordable rental units available once mortgages have been paid off. The chain continues to be weakened at the low end with older buildings being demolished. This normalizes extraordinarily high rents.

The failure of market-based thinking is summarized by a recent piece in the Harvard Business Review.

It’s clear that simply increasing supply, while necessary, is not enough. It is one part of a larger whole. Focus should be on what kind of housing exists, should types of housing are missing, for whom, and how it fits into the broader urban fabric that seeks to improve the quality of life for all citizens. Questions like “What public space amenities should be included?” and “How will it be funded?” are often overlooked in local discussions, along with those looking at the impacts on existing communities, new systems that need to be created to ensure long-term maintenance, partnerships that need to be made to fund across disciplines, and countless others.

Affordability is a complex issue, and pretending otherwise is irresponsible.

The success of Barcelona’s model—founded on its people-first approach—is based on recognizing and engaging the full affordability system. There is no silver bullet. It targets specific income levels and housing tenures, partnership and information systems, funding, and specific measures, ensuring affordable housing is part of a larger strategy that includes open spaces, infrastructure, and urban quality for all citizens.

Barcelona’s approach aligns with the insights of urban planner Alain Bertaud, who argued that affordability requires targeted supply based on household income, spatial needs and other metrics under the “housing consumption” umbrella. He demonstrates that supply does not guarantee a ‘trickle-down’ to populations in need, as seen when wealthy individuals buy up luxury units while holding onto existing properties, charging market rates, or leaving them vacant.

From my personal experience as Chair of the Academic Working Group for Vancouver’s Mayor’s Affordability Task Force years ago, I’ve witnessed firsthand how the City lacks meaningful targets for households in need. I also saw how critical data on spatial attributes, necessary for informed decisions, was not collected, blindly leaving the market to “work out the details”.

Vancouver’s “hyper-capitalist”pro-market, high-profit system biases limited building types—highrises, for example—even though they come with the highest construction costs. Barcelona, with three times Vancouver’s population density, houses most of its residents in 5-8 storey buildings while maintaining a strong urban environment. This balances the quality of life for all inhabitants with the development industry’s needs, showing that density and affordability are not dependent on highrises or “selling zoning”.

Markets tend to produce homogenous products that maximize profits for the few at the expense of the public good. This hinders its ability to address diverse housing needs. In contrast, Barcelona’s approach, focuses on diversity…of tenancy types, building types, and funding models, to name a few, while leveraging both new and existing buildings.

While Barcelona still faces challenges, as Eduard Cabré Romans points out, it has made more meaningful progress than Vancouver, largely due to its foundational values and commitment to taking responsibility for housing—in the service of all its citizenry—instead of irresponsibly leaving it to “hidden hands.”A sentiment captured by Javier Buron: “Housing is too important to be left exclusively in the hands of the market.”

Words to live by.

With this context in mind, we can now compare the key strategies of each city. As mentioned earlier, do not be fooled by their similar names. They operate in fundamentally different ways. Let’s see how…

***

Other pieces in the Barcelona Chronicles:

- Part 1 – Introduction

- Part 2 – Cerdà and Colau: Two Key Figures

- Part 3 – The Barcelona Housing Policy 2015-2023 Overview

- Part 4 – Defining Affordable & Social Housing

- Part 5 – Supplying Affordable Housing

- Part 6 – The 30% Measure and Others

- Part 7 – Vancouver v. Barcelona – Foundations

- Part 8 – Barcelona v. Vancouver – Strategies

- Part 9 – The Eixample and the Superilla

- Part 10 – The Superilla Pilot

- Part 11 – The Superilla…Evolved

- Part 12 – Vancouver v. Barcelona – Urban Design

- Part 13 – Reflections on Two Cities

**

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.

2 comments

The idea that Vancouver is hyper-capitalist is laughable. Apartments are banned on 90% of city land, and nearly all city plans come with overly complex rezoning regulations that include affordability mandates. Additionally, all residents must pay substantial development fees if they want to live in new housing. A significant portion of land is also restricted to industrial or agricultural use. If you want to see what a true free market approach to housing looks like, look to Japan, where broadly permissive and standardized national zoning, combined with an excellent transit system, makes sprawl much more manageable.

Thanks for your note, East Dakota. I wish I could take credit for the “hypercapitalist” label. Unfortunately, the honour goes to many people who have a lot more direct experience with the inner workings of development than myself. I’m sure they’d be equally apprehensive about your statement…as I am.

Regardless, your discontent with the label means nothing to the overall argument. Barcelona’s system is based on different values within which citizens are prioritized at all levels. Vancouver’s, in contrast, masks itself as “people-first” while creating policies otherwise.

I am curious, however, about your understanding of the Japan’s system. Their approach and issues pre-date “modernization” and go back, at the very least, to the Meiji period and its closed feudal system. Japan is a country, not a city, made up of different cities with different systems based on specific historical circumstances. So, calling a whole country “hypercapitalist” and comparing it to a single city is both strange and flawed. It also shows a superficial understanding of the urbanism there. Their visual similarities hide major structural differences.