[EDITORS NOTE: This piece seeks to answer a simple question by a community member: how could the City decision-making about the Broadway Plan be so different than the community at large? And although Christina DeMarco and Erick Villagomez are the primary authors of this piece, it owes a lot to many experts—who will remain unnamed—who offered feedback and insights, while ensuring accuracy. These people ranged from developers to urban planners, architects to urban designers, and provided a wide cross-section of those knowledgeable in planning and development.]

Contributors: Christina DeMarco & Erick Villagomez

In November 2024, despite urgent calls for a pause, the Vancouver City Council approved rezoning for several contentious developments. These approvals permit 18-storey high-rise towers in quiet duplex neighbourhoods and areas with older, affordable rental buildings. The potential development rights, established under the Broadway Plan adopted in 2022, were made possible through individual rezoning applications.

For many, these approvals were a stark wake-up call, exposing the Broadway Plan’s overly complex and far-reaching implications for current and future Vancouver residents. Critics argue the Plan is built on short-sighted assumptions that may ultimately fail to resolve the city’s housing crisis.

Some of these developments were granted densities nearly ten times the current zoning limits while being exempted from community amenity contributions and development cost charges. These decisions—and their consequences—have sparked widespread alarm. Tenant displacement, the loss of older affordable rental units, and their replacement with smaller, often less affordable ones, have been criticized as undermining affordability goals.

This debate underscores a deep divide between critics of the Broadway Plan—ranging from residents to urban planning experts—and the City staff and Council who support it.

How could decisions so misaligned with principles of livable, sustainable urbanism gain traction?

At its core, this controversy reflects conflicting visions for Vancouver’s future.

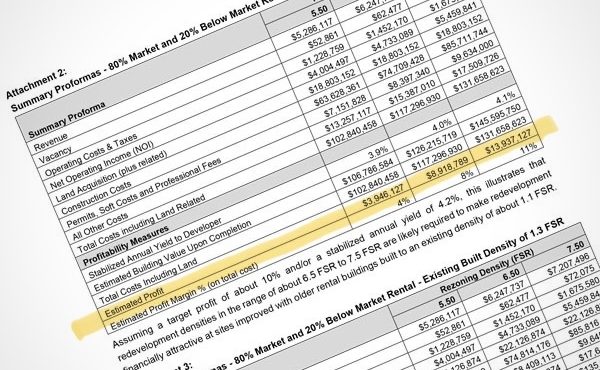

Council and staff defend the Broadway Plan as essential for addressing the housing affordability crisis. By offering significant density bonuses—a current default approach by the City—the Plan incentivizes developers to build rental buildings with a portion of units designated as below-market. Twenty percent of the residential floor space must be allocated to units with rents at least 20% lower than the City’s average market rates.

Critics contend these benefits come at an unacceptably high cost: the destruction of affordable rental homes, tenant displacement, and the erosion of neighbourhoods valued for their housing diversity and character. The rapid pace of speculation and development, with 139 projects underway within two years of a proposed 30-year timeline, has only deepened concerns.

The Broadway Plan’s appeal to developers lies in its reliance on high-rise towers as the primary redevelopment strategy. At the center of this debate is an over-reliance on a narrowly applied and misunderstood tool: the developer-driven pro forma.

A development pro forma is a financial model used to determine project feasibility by estimating costs and revenues. It incorporates variables like land prices, construction expenses, financing, profit margins, and market assumptions. While pro formas are indispensable in the development industry, their reliability depends heavily on the assumptions that underpin them. Developers often tailor pro formas for different purposes: one version to negotiate land purchases, another to secure financing, and yet another to demonstrate project viability to city planners.

Ideally, a city like Vancouver takes a more comprehensive approach accounting for broader impacts such as community costs and the long-term consequences of redevelopment. Instead, the Broadway Plan’s building heights and densities were largely shaped by developer-driven pro formas aimed at encouraging land assemblies and large-scale redevelopment. Influenced by industry lobbying, land economists, and city real estate staff, this approach prioritizes high-density rental towers as the most financially viable option for developers. Towers are predictable, scalable, and highly profitable, particularly since upper-floor units command premium rents.

This narrow focus sidelined smaller, incremental housing options, such as low-rise or mixed-use developments. Often led by local or independent builders, these projects do not align with the profit-maximizing framework of large-scale developers and were therefore deemed less viable—despite their potential to foster diverse, inclusive communities.

Historically, Vancouver has used pro formas responsibly to test market feasibility and determine appropriate developer contributions, which have funded vital community amenities such as parks, schools, and non-profit housing. Critics argue, however, that the Broadway Plan marks a troubling departure from this practice. Developer-driven pro formas for rental buildings now dictate density levels, prioritizing profits over preserving rental housing, maintaining neighbourhood character, or encouraging housing diversity.

The unintended consequences are clear and stark: the promise of higher-density development has fueled land speculation, driving up land prices and undermining affordability—the very issue the Plan seeks to address.

Critics also question whether the 20% below-market units in new towers will provide meaningful relief, as rents remain prohibitively high for most households. Furthermore, there is skepticism about the sustainability of these below-market units, given the private sector’s tendency to renegotiate terms when profits decline.

The Plan’s preference for high-rise towers also raises concerns about tenant displacement, rapid neighbourhood transformation, and diminished housing diversity, particularly for families and low-income residents. Alternatives like the City’s Secured Rental Housing program have demonstrated that 6-storey developments with 20% below-market units can achieve the necessary density without the disruption caused by high-rise towers. This approach would also ease the development pressure on existing rental housing.

Why, then, are 18-storey high-rises being favoured over more neighbourly and environmentally sustainable 6-storey buildings?

Concentrating high-rise towers along Broadway and near transit hubs, while preserving lower-scale developments in surrounding areas, could strike a balance between density, housing diversity, and livability.

Adding to the complexity is the Province’s imposition of its own pro-forma-driven legislation mandating minimum densities near transit hubs. This one-size-fits-all approach often ignores local priorities, including preserving rental housing and ensuring community amenities like schools and parks.

The flaws of the Broadway Plan highlight a broader tension between the financialization of housing and the aspiration to treat housing as a social good. By allowing developer-driven pro formas to dominate, the Plan prioritizes short-term market interests over long-term sustainability and community-building.

To move forward, Vancouver must rethink its reliance on developer-driven pro formas as the foundation of urban planning.

A balanced approach—one that integrates financial feasibility with community values, urban design, and sustainability—is essential. Senior government involvement is also critical to address housing needs that the private market cannot meet, ensuring housing is treated as both a necessity and a right.

The Broadway Plan represents a defining moment in Vancouver’s urban development. It challenges the city to answer a fundamental question: What kind of city does Vancouver aspire to be? Beyond density targets and financial models lies a profound responsibility to build communities that are functional, inclusive, resilient, and vibrant…not simply abstractions.

As Vancouver navigates these challenges, it has an opportunity to lead by example, demonstrating how to balance development pressures with sustainability, diversity, and livability. The stakes—a thriving, equitable city—demand bold, thoughtful action. Vancouver must decide whether its legacy will be one of hasty, shortsighted growth or a visionary commitment to a city that serves all its residents for generations to come.

***

Christina DeMarco is a former planner for the City of Vancouver, Metro Vancouver and Sydney and Perth, Australia..

Erick Villagomez is the Editor-in-Chief at Spacing Vancouver and teaches at UBC’s School of Community and Regional Planning. He is also the author of The Laws of Settlements: 54 Laws Underlying Settlements Across Scale and Culture.