HALIFAX – On May 24th, Halifax Regional Council approved an extension of Halifax’s water service boundary to allow a 256 unit development in Beaver Bank, a bedroom community. You can see how city planners and Council thought the proposal reasonable. If you look at a map, it seems like it makes sense to just fill in the gap.

Halifax Water said it was a good idea: the developer will pay for a watermain between the two neighbouring areas. Why not change our growth boundaries to allow another business-as-usual development?

Because car-dependent growth has enormous, well-established costs that could be avoided with complete rural and suburban communities. It’s time these alternatives become the new minimum standard.

But first, let’s look at the costs.

Health Costs of Car Dependency

At Beaver Bank’s current person per household, this development will house 742 people. That’s half the population of Chester outside Halifax’s transit service boundary, where they also will have no local businesses or services to walk or bike to.

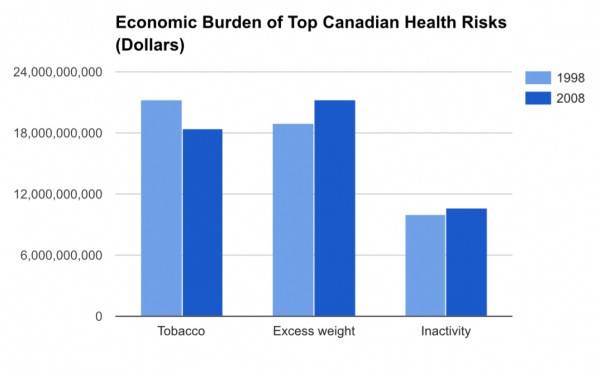

Of course, this is nothing new: an enormous proportion of Halifax’s development is 100% car dependent. But if it’s normal, does that mean it’s OK? Consider this table:

While the health costs of smoking are dropping, the costs of being overweight and inactive are rising to take first place in health costs in Canada.

So how do we combat this health crisis? No matter how great our advertising campaigns, we will likely never convince every Canadian to go to the gym three days a week. Fundamentally, if we want Canadians to walk or bike, we have to build communities where people have things to walk or bike to.

And consider the human cost. According to UK’s Department of Health, inactivity leads to a 16% to 30% greater risk of premature death. If car dependency is a leading cause of inactivity, how many of our 742 new residents in Beaver Bank will die prematurely because task-oriented walking is not option? The number will likely not be 0.

All these people will drive through other people’s communities, where residents will breathe in fumes and fine particulate pollution. Drivers and pedestrians alike will die in car accidents, the 9th leading cause of death in the world. It’s not fair that even people who walk or take transit suffer the health consequences of other people who have been forced to drive.

Drinking during pregnancy was once seen as normal. Smoking was once seen as normal. 100% car-dependency may now seem normal, but for most of human history, it didn’t exist, and considering the health impact, it need not seem normal in the future.

Financial Costs of Car Dependency

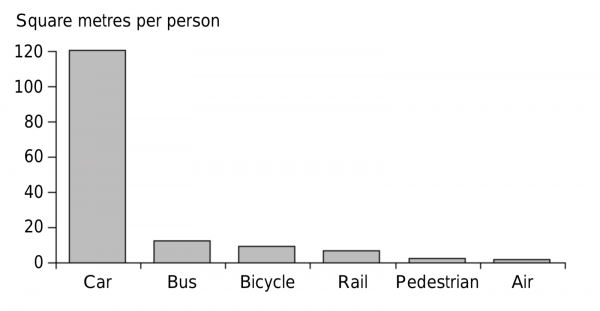

Single occupancy vehicles are inefficient in their use of space and are expensive to accommodate.

Find this graph hard to believe? Consider this image:

Our quality of life is better when driving is an option, but how much are we willing to spend on driving being the only option?

If Halifax’s next 100,000 residents need to drive for every task, consider how much more we will have to spend on infrastructure to handle that level of traffic. If just half of their trips can be handled with sidewalks or bike lanes to local schools and business, or by transit, we will save millions.

Costs to Service

Stantec Inc found Halifax could save $3,000,000,000 over 18 years by better concentrating growth. The reason is simple: if a property is three times wider, it costs three times more to build pipes and roads to it, to pick up its garbage, to plough its snow, to police it, etc.

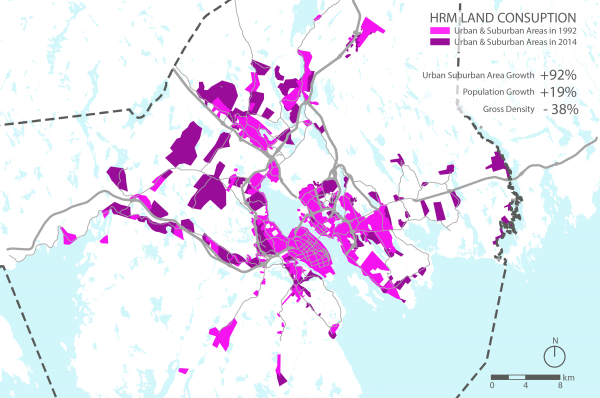

Between 1992 and 2014, Halifax’s built-up area doubled in size while it grew in population by only one fifth. For each person, we now all need to pay for far more infrastructure, and for all that space to be serviced weekly.

While growth should be making Halifax wealthier, dispersed car-dependent development is instead burdening each of us with greater costs.

Costs to the Environment

Personal vehicle use is the largest direct source of CO2 emissions of Canadian households. There is no mystery how cities can reduce that number:

Costs to Autonomy

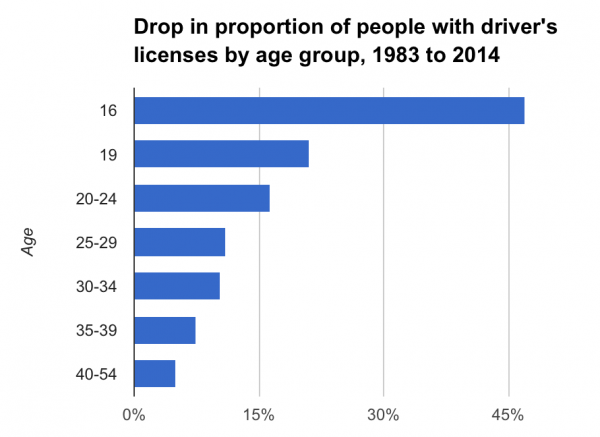

Fully one third of Canadians do not have driver’s licenses. That number includes youth, the elderly, the disabled, and people too poor to own a car.

What does it say about our attitudes to these people if so much of our growth denies them basic independence? I grew up in a poor family of seven with one car in a car-dependent community. Like me, too many young people have no access to jobs and other opportunities until they leave home.

Personal Costs

Owning a car costs $9,500 a year on average in Canada. If the design of a community requires a family to own a second car, it can add $237,500 to a 25 year mortgage. The difference makes many homes that seem cheap up-front cost significantly more, in effect, than transit-oriented homes (pdf). That’s why, in part, car dependent home values plummeted during the housing crisis while the value of transit-oriented homes stayed stable (pdf). What would happen to the value of these homes in an oil shock, if the price tripled or quadrupled?

Are home buyers rationally accepting these costs and risks at purchase? Or are some of these costs hidden to buyers, systematically distorting the market to encourage unhealthy development? It’s an empirical question, but it is hard to believe we would have the same Halifax if home-buyers could see the full equation up-front.

Saying No

The facts about car dependency, inactivity and health are not controversial. What’s controversial is doing anything about it.

Public health initiatives such as Nova Scotia’s Thrive Strategy express the need to build healthy communities that foster physical activity. That much is easy to say, but by failing to directly address the heart of the issue—the construction of places where walking to fulfill practical needs is not possible—these strategies allow the problem to persist.

The attitude of many in government appears to be that while we shouldn’t continue to allow this kind of development, we can’t not allow it.

In fact we can. A piece of land has zero development value unless taxpayers provide it with roads, pipes, and a commitment to service it with garbage pickup, snow ploughing and much more without end. Just because someone happens to own a piece of land does not mean they have a “right” to reach into taxpayers pockets, create an infrastructure liability, and get away with large profits.

That’s why under Canadian law, it is municipalities that decide where subdivisions can be built, not land owners. One of the most decisive legal cases on this issue was actually decided in Nova Scotia, and the outcome was clear: land ownership does not equal an absolute right to residential development. Ontario has used this power to say no to subdivisions in an area nearly the size of PEI.

Saying Yes: Complete Rural and Suburban Communities

There are, in fact, many Halifax communities that are actively trying to create attractive local mainstreets where residents will be able to conduct much of their daily business on-foot: Musquodoboit Harbour, Tantallon Crossroads and Village on Main (Dartmouth). We need to support these efforts by directing our scarce yearly growth to such places.

Many people do prefer living in car-dependent places. Happily, we can already offer 10’s of thousands of car-dependent homes, and space for thousands more have been approved. This preference is well-served. Considering the health and cost consequences, however, approving more is unethical.

A Basic Minimum Standard

“Not all urban development is good just because it is urban. Not all suburban development is bad just because it is suburban.”

These words—spoken by a planner representing 265 unit development in Beaver Bank—are no doubt true. But if the health data is correct, car dependent development, whether rural or urban, is indeed bad. In fact, the numbers are clear: it leads to illness and premature death.

We must abandon the idea that it is permissible to build communities where driving is the only option to do anything. We must set new minimum standards for growth so all new communities will be complete communities. A proportion of commercial space should be required within walking distance of homes. We need rules for street layouts that allow people to walk in the most direct way possible to destinations and street-design standards that make walking and biking safe and comfortable. We should require new growth to achieve a reasonable levels of compactness, while maintaining the privacy and space that makes rural and suburban development attractive.

It would not be considered professional for authorities in the health sector to play a role in encouraging smoking. Currently, however, it is considered professional for planners to enable development that constitutes a leading cause of illness in Canada.

All this raises a question: given the evidence on health alone, how can we continue to accept that car-dependent development is part of professional planning practice? How good does the evidence need to be before we update what we deem ethical?

It is time to set a new norm: the only good development is complete development, where healthy forms of transportation are at least an option.

4 comments

Complete communities. Yes. Everyone knows them when we see them. People go on holiday just to walk in one.

One more point. Next to the big banks nothing conveys wealth out of a rural region faster and more efficiently than new car dealers. Economies need capital to grow productivity and make investments. New cars, more than any other household expenditure extract capital from our economies.

Of a typical $30k new car, less than $1000 even makes one stop in our economy, the rest, plus the bank financing cost, plus the uncovered infrastructure costs, gas and insurance is an unmitigated outflow of wealth.

If you wonder what’s wrong in our rural region. If you wonder where our wealth is going. If you wonder why there’s no capital to start businesses and develop ideas. If you wonder why growth is completely disconnected from broad-based prosperity for regular people. If you wonder why you can’t get ahead… just look out in the driveway, and all the roads and driveways, and count $100k for every car you see…

I don’t think forcing people to park their cars is going to be successful . Stay the course. Widen the service boundaries and improve public transit and perhaps , empower community councils to govern their communities . Create a system of local neighborhood governance and foster communities, and social planning as part of complete communities , perhaps an organic ot grassroots form of complete communities could be the result.

Thank you for many great points. I could not agree more on the direct relation between planning and health. I’m surprised we are not talking more about this crucial issue. That’s a big picture problem that we will have to tackle, as great cities like Malmo and Copenhagen have for the last two decades. However, we cannot dismiss all the facts when looking at any planning issue. On this particular case, your article is missing key facts that are important in making the water extension the right planning move for this site:

1. Your premise for this article is this:”Halifax Regional Council approved an extension of Halifax’s water service boundary to allow a 256 unit development in Beaver Bank”

This is wrong. The residential density of 256 unit has nothing to do with service extension. In fact, the residential density is already enabled through Regional Plan and has nothing to do with the water extension. The water extension will help the existing and future residents with access to reliable and clean municipal water and it will help improve quality of life for hundreds of people.

2. This land is zoned for industrial use, it’s 300 acres of viable industrial land with access to a main road, but this is at the middle of two residential communities. Taking this industrial land away is the right planning decision. The as-of-right development right here will be the wrong approach.

Not only that, the residential community proposed for here is a “Conservation Design” concept where 65% to 80% of the natural features of the site will be identified and preserved. Unlike typical suburban clear cutting practice, this residential neighbourhood will be designed with the nature and as the nature being the defining feature of it.

3. The water extension here is a very special case and likely would not happen anywhere else in the Municipality. This is an extension that Halifax Water requires to improve the reliability of the access to water for all the residents. This extension will have to happen at some point, should we make it a cost on taxpayers, or worse the residents of the area, or allow for sensible, good infill development at the site?

4. We won’t resolve the health issue by taking out suburban and rural development out of the equation. 60% of Canadians choose this lifestyle, we need to work on the quality of life so people who live in these communities can still have a healthy lifestyle. How can we make these areas more sustainable and improve the quality of life? Conservation Design is one of the best ways of doing just that.

Again, thank you for the stats. Health is probably the most important issue in planning. Let’s focus on making our communities more active. Right now even our urban developments cannot enjoy the benefits of cycling and walking because of lack infrastructure required. Let’s get more bike lanes, reduce incentives for driving everywhere, increase transit ridership, and, most importantly, increase awareness on the issue.

Canadians are bad city planners. Period!