How do we design for identity?

Two weekends ago, I have had the pleasure of attending a small conference within the Chinese community to discuss topics and raise issues that have been both a struggle and challenge to the growth of the neighbourhood. Several inspiring speakers were present, like the ever curious and enthusiastic Dr. Lai (who kind of reminds me a little of my grandpa), as well as interactive sessions that touched upon the cultural connections between Canada and China.

Chinatowns always had this reputation of being these underground spaces that house a string of questionable retail business and lower-class citizens. Yet, if one actually walks into the several buildings and shops located in our Chinatown, I discover much less these spaces of anxiety but rather more absence in a sense of cultural space.

According to Dr. Lai, there are five different models of Canadian Chinatowns:

- The Extinct Chinatown – the death of a Chinatown, where there is no desire or legislative motive to salvage a it (eg. Keithely Creek)

- The Historical Reconstructed Chinatown – one in which certain themes or events that have occurred in that specific urban space are recreated and landscaped again to mimic full scale historical sites (Bakerville, BC)

- The Rehabilitated Chinatown – a revitalized Chinatown, where streets are widened in certain districts, oriental ornamentation and themes are strictly reinforced towards new developments and construction (Vancouver, Victoria, Montreal)

- The Replaced Chinatown – demolition of old buildings in order to build newer, more modern buildings on top, (Calgary) and

- The New Chinatown – an institutional use of the Chinatown area. Although, the presence of a Chinese community would be dispersed throughout the city since the lack of cultural centres and Chinese-based organizations are not available (Ottawa)

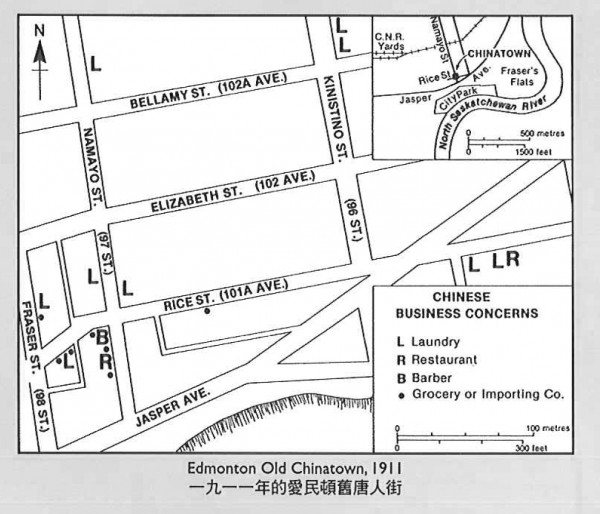

Edmonton’s Chinatown somewhat stands right now as an anomaly where you have the existence of two Chinatowns: North and South, and if you have lived and worked there long enough, the disconnect between the two areas are very obvious.

Chinatown South currently faces two challenges:

- the implications and design consequences of the LRT line expansion, which guts itself through 102 ave in front of the two cultural centres, and

- the relocation of the Chinatown Harbin Gate, which caused much concern. In order for the gate to properly fit between the two proposed sites, the dimensions and design of it will likely have to be altered (not that re-designing something is necessarily a bad thing, but this is most discerning because it was given to the city as a gift from China).

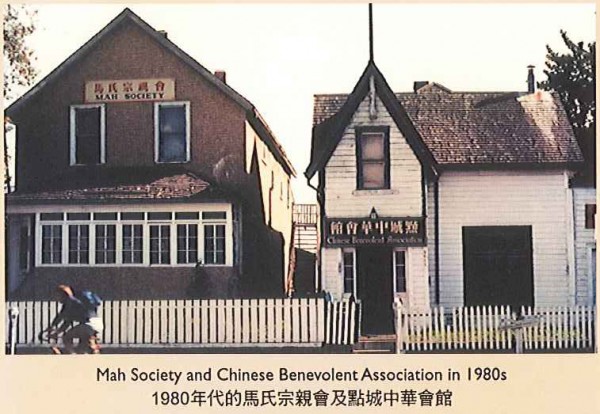

Lai classified our chinatown under the category “replaced” as numerous buildings have been demolished along the 97st strip to make way for new ones such as a new cultural center, a garden, parkade and the Canada Place Building.

I have posted up a few old photographs of what use to exist in the area.

When we move from one city to another, one home to another, we constantly struggle to find an identity that works to preserve where it is we come from while simultaneously letting it grow into our new surroundings. In other words, its always a composite fused together from personal experiences, time, heritage and people. I remember coming back from living for four months in China and all I could go searching for was the best noodle restaurant in town, but ultimately had to make due with what was available. I would also go about looking for a space that could play out that rhythmic sequencing of bicycle bells ringing along with the clatter of flip-flops marching down the street, but I think that small gazebo on 97st is about as close as I can get (although not very encouraging to be there alone during the evening). In doing this, I tried to connect a personal past with my present surroundings.

Despite the amount of rich information that was delivered and presented to the community during the conference, there was a clear absence in the discussing of “the how”, or how I would have like to discuss it, “where is it going and how does this culture shape itself into our unique city?”

What we see “built” in Chinatown today expresses a much desire and need to connect the cultural with the physical. The disconnect comes not only from the obvious four-block separation that we see between the two areas, but a lack in the cultural symbolism that we tend to associate our sense of place with. Thus, physical planning in this case, is not as important as the social planning aspect of this neighbourhood. To design only towards cultural ornamentation and aesthetic answers just a third of our conversation. What is evermore alluring is to discover and form the neighbourhood (both parts) through its local culture and reinterpret those into something modern and uniquely symbolic to that community. So to meditate upon our own Chinatown, the distinct division between the north and the south could set the stage for an ongoing series of buildings and spaces that design only for tradition or modern and never both. But the funny thing is, identity is never either one or the other, it is never singular or stable. It’s organic. And of course, that does become a challenge when you have so many individuals with different experiences and relationships with the city.