Sky. When I talk with Edmontonians-away-from-home about what we miss most about the city, the answer is almost always the same: the sky. The Northern Lights. Thunderstorms. Fiery sunsets. It is one of the things that makes this city liveable, and unites across our many differences. And with our long winters, sunshine is a valuable, renewable, and free public asset.

But as this city grows and changes, how do we ensure that everyone gets a piece of the sky?

I am proud to call myself an Edmontonian, but I am not thrilled about sharing that identity with a 71-storey condominium. “The Edmontonian Sky Garden Tower” proposed by BCM Developments would be located next to the new Arena District at 10525 101st St. “This beautiful and elegant tower will forever change the Edmonton skyline”, reads BCM’s website, “[it] will be the tallest building in Edmonton and one of the tallest residential buildings in western Canada. On the proposed 30th floor you’ll enjoy a sky garden with an unparalleled view of the city’s core.”

With the recent closure of the City Centre Airport, height restrictions have been lifted, and downtown towers can now go as high as 200 metres. The City’s Downtown Plan wants to encourage more development, with taller, sleeker towers. This could bring more life to downtown, which we need, in this sprawling city. However, if this city is set to reach higher and higher, do we understand all the implications of what more tall buildings will mean? Will a view of the sky be something reserved only for condominium owners? Can we identify and preserve iconic Edmonton views? And how do we make these views accessible from eye-level, from street-level? Danish architect Jan Gehl, in his book Cities for People, says we must consider: “life, space, buildings – and in that order.” He says that we must start from the human-scale, from the 5 km/h scale, and scale up from there to the birds-eye view, rather than the reverse.

At ground level, looking east, down 105th Avenue and north, down 101st Street.

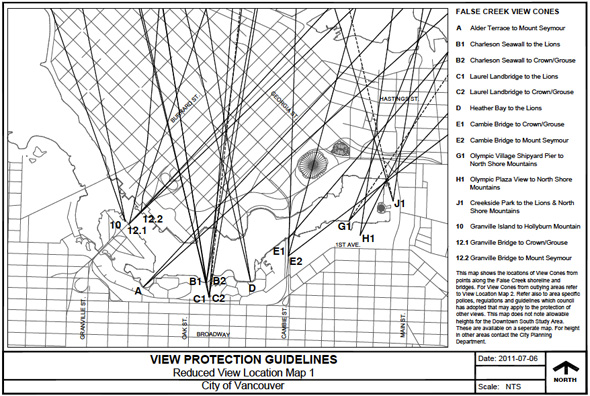

The idea of protecting views is big in Vancouver, where there are 27 protected view corridors, established by the City to protect the view of the North Shore mountains, the Downtown skyline, and the surrounding water, to “ensure that Vancouver maintains its connection to nature while the city expands.” The City of Vancouver has had View Protection Guidelines in place since 1989, in order to protect selected, threatened public views, called “view cones.” The protected view corridors help determine the site location and design of new buildings, resulting in the retention of panoramic and narrow views downtown. Montreal has thought carefully about how to make Mount Royal, the gem of the city, visible fromall directions. The Montreal Master Plan identifies a need to preserve views of Mount Royal from various parts of the City.

As Edmonton changes, as cities are wont to do, we need to mourn the views already lost. The Strathcona Railway Station is one of these. Due to an oversight by both planners and community members, the vista was lost in 2012 to the four-storey Fuzion on Whyte condo and commercial development, also by BCM. People didn’t realize the visual implications of losing a line of sight until after a development permit was approved at a 2007 subdivision and development appeal board hearing. “It wasn’t on anybody’s radar,” said Councillor Ben Henderson, in the Edmonton Journal (May 2, 2012).

What if we could avoid these mistakes in the future? What if we could inventory the views that Edmontonians value, and enshrine these views in city plans, so that the visual implications of developments are on the radar. So that proposed developments must consider the views they will frame or block, so that the public knows which sight lines are valued, so that the City can stand firm at the bargaining table with developers, if need be.

“Oh yeah, we wanted to beat Calgary,” said Sherwood Park architect Terry Hartwig, whose firm first designed The Edmontonian as a 41-storey tower, about six years ago (Edmonton Journal, Nov.1, 2013). The bragging rights to having “one of the tallest buildings in Western Canada” inevitably only last until someone else builds a bigger building. Could we aim for a more thoughtful legacy?

Could we ask that urban development be guided so that there is deliberateness, intention and elegance to how this city unfolds?

Imagine if one day the world will know Edmonton as a city of sky and grace, not a city of big things. That would make me proud to call myself an Edmontonian.

What do you think? What views say “Edmontonian” to you? The Legislature? The High Level Bridge? The Harbin Gate? The refineries that ring the city? The ribbon of green that runs through it all?

One comment

I completely agree that there are views that need protecting. The High Level Bridge, The new Walterdale Bridge, The Hotel Mac, The Legislature (technically already partially protected by the Capital Blvd refurb), The Space & Science Centre, and the list goes on. The real issue is whether it’s really feasible to protect the view of the sky without physically stunting our skyline. I don’t consider the view South on 101st especially fetching, and I’m sure the same could be said of the other views around The proposed Edmontonian tower, so I don’t necessarily see it as an issue. That said, the views from the top will be a showstopper, and I sincerely hope that BCM follows through with a public viewpoint if this every actually gets built.

In a city not surrounded by mountains and oceans it will be an uphill battle to protect the view the sky, the one natural beauty that we all cherish. However, protecting the view of the list above will, in turn, protect certain pockets of sky, and that’s a good start.