Some time ago now, I wrote Part 1 of The Edmonton Streetcar and its Urban Form. In it I identified that Edmonton’s favourite streets are largely historic streetcar routes – anchoring our favourite neighbourhoods and lined by many of our favourite shops. In Part 2 I delve into greater detail to examine what makes streetcar streets great, and the elements we can apply to how we design streets today.

I started writing this article armed with characteristics of streetcar streets to convey, but the best way to communicate their success is comparing the influence mobility changes had on our city since. In this sense, this article is as much about our city’s evolution in urban form away from the streetcar’s influence. Historic streetcar streets were (and remain) our best walkable streets because of:

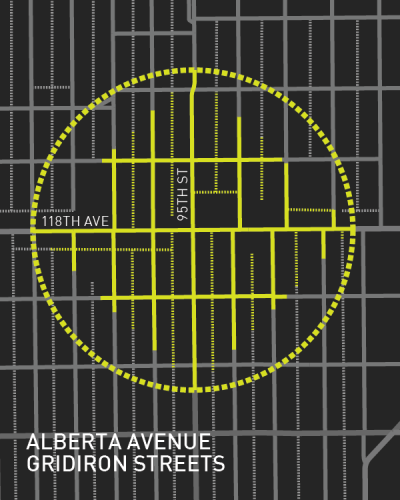

1. walking distance: In a real physically quantifiable sense, surrounding ‘gridiron’ streets and land use were optimized for pedestrian proximity to the streetcar and its arterial commercial spaces.

2. narrowness: Because they were relatively narrow streets by today’s standard, and lined with buildings, streetcar streets were spatially well defined public places designed to the scale of a pedestrian.

3. destination diversity: the small scale nature of retail and community space along streetcar arterials allowed for a multitude of daily functions to be accomplished on foot.

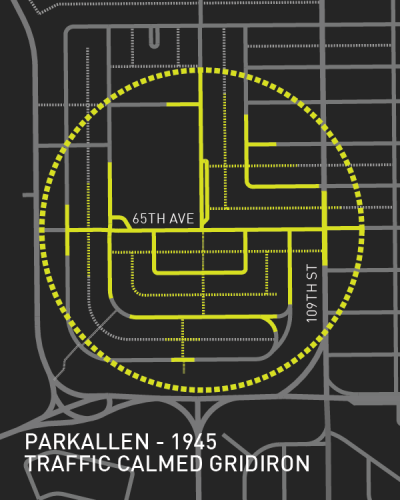

To explain these three main points, below are some simple graphic elaborations. 5 minute walking distance is shown on the maps as a 400m radius, and its limit according to the routes available to a pedestrian from its centre

Gridiron Streetcar Arterials

Edmonton’s traditional ‘gridiron streets’ are typically marked by short blocks, numerous intersections, and alleyways. All contribute to a multitude of ways to walk to the same destination. As discussed in part 1 small scale ‘high street’ commercial opportunities exist as important destinations, where many daily activities can be accomplished nearby and on foot. Community services, a grocer, doctor, clothing retailer, or restaurant serve as examples.

Traffic Calmed Gridiron

The period of the rise of private automobiles and decline of the streetcar, shows how changes in the form of transportation can significantly affect urban form. Postwar street networks are a compromise between traditional gridiron streets, and a resistance to the increasing unpleasantness of traffic. Curved streets deliberately ‘traffic calm’ neighbourhoods by limiting outside traffic to pre-determined routes. Some small scale commercial opportunities are still preserved, and a permeable network of walkable streets is maintained. For further discussion I recommend Troy Smith’s essay.

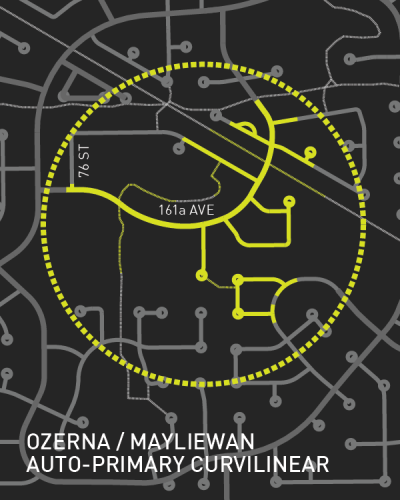

Auto-Primary Curvilinear

With its curvilinear streets and cul-de-sacs as functional dead-ends in a network, contemporary Edmonton contains many poorly connected areas marked by a single land use. Parks and playgrounds do serve as local destinations, but small scale retail and community services in close proximity to homes is sparse to non-existent. It is not a stretch to say many must burn a litre of gas to buy a litre of milk in many areas of the contemporary city.

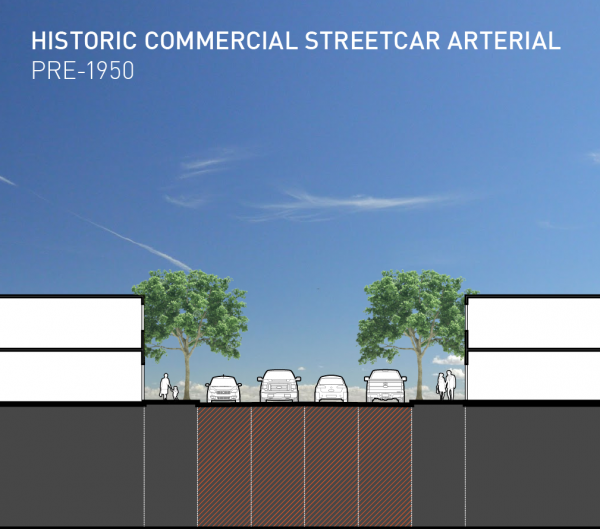

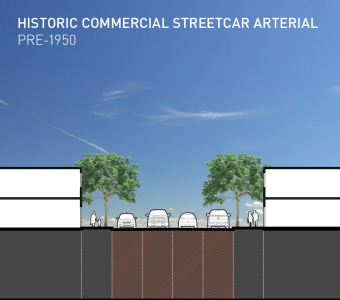

Historic Commercial Streetcar Arterial (Pre-1950)

When the above street section is seen in a side-by-side width comparison with images following, it is readily apparent: historic streetcar streets such as Alberta Avenue are comparatively narrow. 1-2 storey buildings on either side of the street form a ‘streetwall’ and spatially define it. Building variety, materials, and landscape details contribute to place. Crossing and jaywalking are common because it is easy, relatively safe, and quick to reach a destination on the opposite side. Shops provide numerous finger thawing locations on frigid days. Windows abutting the sidewalk perform a safety function; surveillance has proven to alleviate both real and perceived danger.

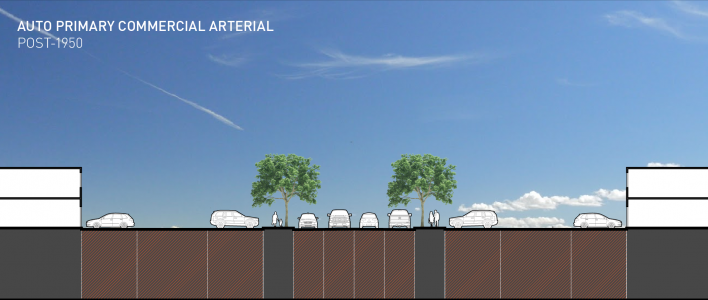

Auto-Primary Commercial Arterial (Post 1950)

Commercial transit arterials during the transition from streetcar to automobile also reflect a compromise between modes. The obvious observation here is the space required for cars. To accomodate storefront parking, the window to window width is over triple that of the streetcar arterial. Sidewalk pedestrians are between parked and moving cars instead of window shopping in this section. The sense of space is lost, and the functional crossing width erodes walkability and attractiveness.

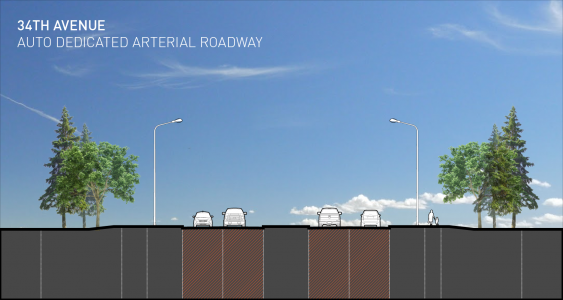

Auto-Dedicated Arterial (Contemporary)

Further in the evolution to private automobile dominance, public life ‘streets’ disappear in favour of ‘roads’; the main purpose is carrying vehicles at great distances most efficiently. While the pedestrian experience may not be the last thought in auto dedicated arterial roadways, it is far from the first. Sidewalks are provided, but pedestrians walk here more by necessity than incentive. There are few reasons to linger, aside from an interest in traffic gazing from the odd park bench provided. Residential layouts rightfully turn their back (yards) on these roads with a noise and visual screening fence; emphasizing a disengagement from public street life that older designs once inspired. Everyone who has lived in Edmonton long enough has been down this ubiquitous road many times before.

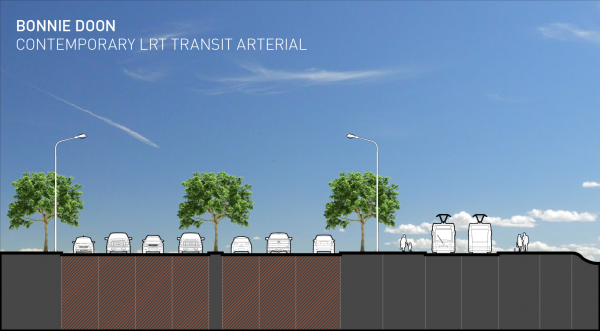

Transit Arterial (Contemporary / Future)

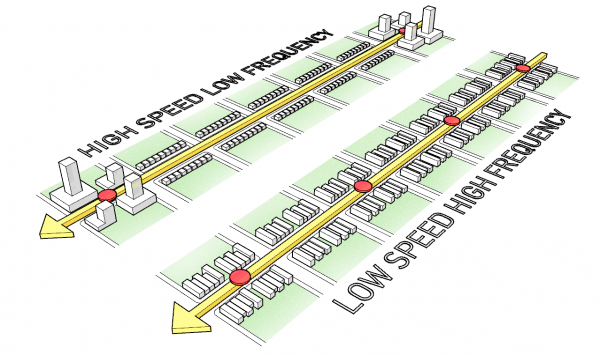

What about the streets of our planned future? If the question is ‘how do we again design attractive and walkable streets?’, the answer decisively includes transit purely based on space demands. The type, urban design, and integration with suitable surrounding land uses will determine success. Recently planned and constructed LRT routes (illustrated above in future Bonnie Doon) have typically included expropriation of land and widening road right of ways to accommodate tracks and station platforms, while maintaining all automobile lanes. Trains travel at relatively high speeds with great distance between stops, meaning little opportunity for integration with the surrounding land uses between stops. The effect is that development influence in this respect is limited to distinctly separated ‘nodes’. Malls like Southgate are easy targets for transit stops and redevelopment, and clusters of density in large scale projects like Century Park are more probable.

The streetcar on the other hand travelled slower and stopped frequently. The integration with the surrounding landscape was higher, and reflected the nature of streetcar streets as linear interconnected public spaces. Development pressures were not limited to specific transit nodes, and tended not to surpass midrise level along routes. Land ownership further emphasizes the picture: Streetcar routes generally formed along avenues lined with houses, contributing to ‘fine grained’ urban fabric made up of small buildings and parcels. Numerous lots spread over great distance makes land assembly more difficult, even for the well financed. This leads to a moderate scale of buildings and development projects, distributed more evenly along the streetcar arterial. Limited hard infrastructure was required to add future streetcar stops along an existing line, making the system resilient and flexible to demographic and density changes. The streetcars themselves were relatively lightweight and able to use existing roadways and bridges.

A caveat to address briefly is the bus: as a replacement for the streetcar at a similar speed and stop frequency, without the relationship to attractive streets. data supports the streetcar attracting greater ridership and investment. Streetcar tracks communicate to riders where to board and the direction they’ll go, while bus routes can be nebulous for a novice. Once streetcar tracks are laid, an investor has relative stability given the route won’t likely change. See additional with varying viewpoints.

Now that we’ve covered how the past established the present, how do we use what we know for the future? Pedestrian values were embedded by default into our streets at a time when all Edmontonians were pedestrians, but were gradually lost as most of us became commuters. For many favourite neighbourhoods a great street is the backbone of its desire. There is an immense and worthwhile focus on redeveloping downtown, but it shouldn’t allow us to overlook perhaps a greater civic cause. One is the all important icing on the cake, the other is the bulk of the cake. All Edmonton neighbourhoods deserve an attractive walk to meet many daily needs, which is a tough thing to cite anywhere outside of a central area developed after the 1960’s. Getting there will require a mental shift: from the single engineered function of roads, to the complex and social functions of streets.

For reference, below I have included Google Streetview images of the types of streets I have referenced in street section drawings.

Alberta Avenue

Beverly

34th Avenue

Bonnie Doon

Jason Pfeifer is an Edmonton based Landscape Architect and Urban Designer, and Principal of PD+A Studio, a boutique service-oriented interdisciplinary design firm.

One comment

Great article! It’s good to see this type of discussion and critical thought happening in my city.