Originally published in the winter 2014 issue of The Yards. Written by Omar Mouallem.

Shortly after the CN Tower was completed in 1966, the City of Edmonton’s planning department produced a fact sheet with an illustrated timeline depicting all a developer needed to know about the Gateway to the North. The final milestone included a utopic drawing of Edmonton’s downtown skyline—with what was, for a brief time, Western Canada’s tallest skyscraper at its centre. Below it, this caption: “Modern Edmonton, a lusty young giant and the key metropolis in Canada’s next 100 years.”

Ironically, it was around this time Downtown started becoming anything but vigorous. A giant, maybe, but a lethargic one that slept for 16 hours a day. By the 1970s, it was in bad health, sick from suburban flight, uni-functionalism, insular buildings and pedways that robbed the streets of life and history. Its nervous system flowed with cars and its heart beat ever slower. How did this happen during Edmonton’s most prosperous time?

The image of a lifeless city centre is unrecognizable to many who live there today. The core is in recovery mode, largely thanks to a reverse exodus of people who’ve made Downtown and neighbouring Oliver two of Edmonton’s fastest growing neighbourhoods. Many, if not most of them, are too young to remember the dark days, or are new to the city. Had they been here 50 years ago, there is something they’d recognize right away: a mind-boggling construction boom.

Once again there are more cranes in the Downtown skyline than you can count in one gaze. What will the end result be? The changes are happening so fast that it’s hard to predict, but if we understand the past we can help shape the future.

‘Nowhere a More Buoyant People’

One-hundred and twenty years ago, Edmonton’s most prominent feature wasn’t buildings, cars or people. It was trees. The governor general’s wife described the city after her 1894 visit as “Pretty scenery with plenty of timber, very different from the dreary prairies.” Three years later the Klondike rush arrived and Downtown’s quaint character gave way to a real estate boom.

The rail yards and station built by Canadian Northern Railway, along what’s now 104 Avenue, opened in 1905 and accelerated development. While the province’s first newspaper owned by politician Frank Oliver (namesake for the Oliver neighbourhood) called for expelling the Cree, Eastern Canadian and European families arrived to Jasper Avenue with freights of livestock and heads full of dreams. “There could be nowhere a more hopeful or buoyant people than the Edmontonese,” wrote The National Monthly of Canada. “They look upon themselves as being the makers of a city that will surpass Winnipeg in time.”

Others insisted it was the next Chicago, but Downtown was still a playful infant. “On Saturdays,” writes Tony Cashman in When Edmonton Was Young, “a popular form of relaxation was jumping fully-dressed into the horse trough at Jasper Avenue and 95 Street … a grand spectator sport for kids of the neighbourhood.”

Soon Downtown had six theatres, the dome-topped Alberta Legislature dwarfed the riverbank’s old fort and the McLeod and Tegler towers cast shadows on the surrounding shops. Those who’d spent a few hundred dollars on Jasper Avenue properties flipped them for hundreds of thousands.

But it was pure luck. The First World War stoppered immigration, the bubble burst and Downtown’s dreams were put on hold.

‘Marred By That Unsightly Block’

Despite the Great Depression, Downtown was determined to become something befitting of the city’s capital status. There was little money, just ideas. The local government bought up cheap land surrounding CN’s new station, slated for completion in 1928, hoping to construct an attractive civic centre that would impress newcomers the moment they stepped off the train.

Complete with a natural history museum and standalone art gallery, you could call it Downtown’s first revitalization project. Like the forthcoming arena district, it dragged on for years—decades even—due to its costs and lack of government support.

In 1943, JW Sherwin, an academic and writer, explained his impatience in a letter to the mayor, recounting King George VI and his Royal Family’s recent visit: “I was one of the thousands who stood or was crowded in front of the Macdonald Hotel on that memorable and now almost historical night. … I have often tried to visualize since, what their impression was when they smilingly looked down and waved their hands to that enthusiastic audience, almost one of their last appearances, and the whole scene marred in its background by that unsightly block of antiquated frame shack stores and their backyards.”

Then, in February 1947, Leduc No. 1 filled 41 barrels of oil in its first 60 minutes. Three months later, Edmonton’s planning commission presented a renewed civic centre plan even grander than the first. A plebiscite for the plan was held in 1950. But the public rejected it.

Perhaps Edmontonians were busy cashing in on a modern dream. As Linda Goyette put it in Edmonton: In Our Own Words, “Young developers became millionaires because they supplied a treasure more valuable to families than all the black gold in Alberta: an affordable home.”

Downtown hardly needed a boost from the public coffers anyway. Modernist masterpieces, such as the AGT Building, Toronto Dominion Bank and Centennial Plaza, blossomed from those former shacks and yards. In time, a new city hall, library and art gallery would bring the civic centre to near completion, while CN planned a new station inside its striped marble-clad tower. Also in the works was North America first light-rail transit system, intended to connect the city’s growing extremities—suburbs and subdivisions—to its heart. Out went the ground, up went the cranes.

There were few critics of Downtown’s “new look,” as it was called, perhaps because fewer lived there. It became less a neighbourhood than a public works project, and those who spoke out were laughed down by boosters, such as in this 1965 Edmonton Journal editorial: “A modest stroll through the business section of the infant city just before the 1914-18 war would have been enough to send the architectural purists to the sidewalk of that latest wonder, the High Level Bridge—with thoughts of jumping off.”

Going Big

In July 1972, as throngs of people in dapper hats, corsets and furs crowded Jasper Avenue for the Klondike Day Parade, a wrecking ball smashed through the neo-classical courthouse a block away. Parts of its exterior went to the provincial museum for exhibition. That was the boomtown mentality. Sixty-year-old sandstone: artifact.

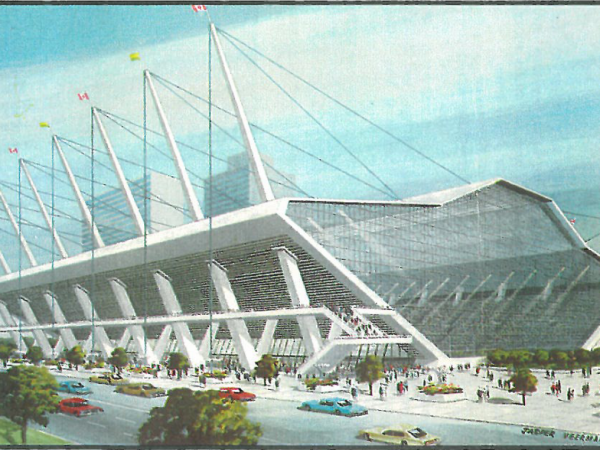

The iconic courthouse, Victorian post office and King Edward Hotel—all razed for glassy and concrete offices of an inhuman scale and parking lots to support them. The few planned social spaces were insular and threatened to vacuum what little street life remained, culminating in the half-baked Omniplex proposal—an all-in-one football stadium, hockey rink and convention centre.

“Going big” had serious consequences to the feeling of being in Downtown. For one, it resulted in a rush of the hideous concrete residential and office towers that still define it today. Meanwhile, the commercial buildings, connected by pedways, turned their backs to the streets, repelling rather than encouraging life in public spaces. As well, zoning changes that attempted to increase density increased land values, so property owners were more inclined to sit on their parking lots waiting for investment that never came.

It wasn’t just the residential potential that was grim. The Hotel Macdonald was falling into disrepair and other surrounding businesses were shuttering or moving to malls in droves. More would follow when West Edmonton Mall opened in 1983, awakening residents to the core’s undeniable lameness. Until then nothing could crush the boosterism.

Leading up to the 1978 Commonwealth Games, Mayor Cec Purves announced, “We won’t be mistaken for a dot on the map any longer.”

Throwing Things at a Wall

For a while it felt that way. The games, the Oilers, SCTV and the planet’s largest mall attracted unlikely attention to Edmonton and its core.

On assignment with the New York Times magazine in 1985, Mordecai Richler observed about Wayne Gretzky’s home: “There is hardly a tree to be seen downtown, nothing to delight the eye on Jasper Avenue. On 30-below-zero nights, grim religious zealots loom on street corners, speaking in tongues, and intrepid hookers in miniskirts rap on the windows of cars that have stopped for traffic.”

It wasn’t without warning. In a 1979 civic report, architect R.L. Wilkin said that Downtown had become uni-functional as an area devoted to the service sector. “The future of downtown Edmonton as a substantial residential area does not at this point look bright.”

Despite his sobering words, attempts to revitalize it focused on megaprojects, including a $100 million plan that included a “world-class” concert hall, a renovated Chinatown, an outdoor mall dubbed the “Towne Market,” a theme park and fantasy fair. Indeed, it was a fantasy, one quickly halted by economic recession, high mortgage rates and austerity programs. However one was realized, the mall now known as City Centre. The private-public partnership cost nearly the same as the new arena and was contracted to the billionaire family behind West Edmonton Mall. It was supposed to help Downtown recover from their very creation. The proposal was repeatedly watered down and never met expectations.

Despite the addition of beautifying new streetlights and meridian globes few would walk the area after work. “Have you ever gone for a walk in downtown Edmonton at night?” asked Olive Elliot in a Journal column. “The city is transformed by shadows and light and takes on a new, moody beauty that is never suggested by day. Unfortunately, many Edmontonians know nothing of such experiences because they have grown to fear the streets at night. Stories of robbery and rape, assault and harassment seem to fill the news pages and the impression of mean streets sinks deeper into public consciousness.” But more than anything, there just wasn’t much there to do.

That was less true in nearby Oliver, which saw a budding community of students, gays and seniors, drawn by cheap rent, who patronized what few bars and cafes existed. It seems obvious now that the difference between east and west Downtown was residences, but it would take another decade to draw that conclusion.

An opportunity to correct mistakes arose after CN finished dismantling the rail yards in the 1990s. The city planned a dense community of walkups and townhouses that would essentially extend Oliver northward. Instead, “market forces” overturned the idea and 104 Avenue took on a suburban form with traffic planning so pedestrian-unfriendly that one city councillor even argued for buffers keeping unwanted pedestrians from slowing her commute. None were needed; the strip malls were barriers enough, further dividing residents of Downtown and Oliver from surrounding neighbourhoods.

Downtown is for People

And then, in 1997, an epiphany: Instead of trying to attract people to Downtown, what if people lived there?

At the moment there were about 5,100 residents in Downtown proper—fewer than there were five years earlier. City Council approved a $30 million Capital City Plan that focused not on commerce, but on homes. There were some beautification ideas to attract residential developers, first on the 104th Street Promenade, but the golden ticket was a generous grant program that the city hoped would nearly double Downtown dwellers to 10,000.

It’s since exceeded that by over 3,000. Oliver’s population also ballooned, and now counts 20,000 residents. With the number of Downtown residential condos and apartments under development, it’s safe to say the two regions will be home to nearly 40,000 Edmontonians by 2020. Surrounding Central Edmonton neighbourhoods—McCauley, Boyle, Central McDougall and Queen Mary Park—haven’t seen as much growth but are on their way with various infill. And only 20 years later, the City has acknowledged its mistakes with the former rail yards and is attempting to undo the barrier by re-imagining 104 Avenue as a pedestrian-friendly, mixed-use corridor.

Yet when we talk about Downtown’s revival, the focus tends to be on the new cafes and boutiques, the megaprojects, the hotels, the cranes, the holes—instead of the people. Certainly, the commercial upswing has made Downtown noteworthy again, but without those thousands of urban pioneers none of it would have happened.

According to the 2014 census, about 40 per cent of new Oliver and Downtown dwellers arrived from outside Edmonton. They’ve helped renew the optimism, projecting upon Downtown their idea of what a capital city should look and feel like. But a city with our in-migration—one of the fastest in Canada—grapples with a lacking sense of history. In its third quest to becoming “world-class,” Downtown must learn from its mistakes.

As far as it has come, Downtown still lacks the vitality of most other cities of 1 million. Will the current boom spread its successes—the reinvigorated Warehouse District, Jasper Avenue and 124 Street—to the rest of the core and Edmonton’s other straggling promenades? Or might it do the opposite, drive people out who can’t bear the construction or afford to live there anymore?

The focuses on infill, higher density, appealing architecture, entertainment and walkability are a step in the right direction—though they shouldn’t come at the risk of historic erasure, class exclusion or street life. And we must acknowledge the obvious: The second oil boom enabled Downtown’s renaissance as much as the urban pioneers have. It’s offered us the chance to build it right this time, but we can’t know for how long it will last. If and when the well runs dry, what will keep up Downtown’s momentum?

Omar Mouallem (@omar_aok) edits The Yards and writes a weekly column in Metro News.