Until around the mid-twentieth century, almost all subdivision plans for Edmonton were conceived as a traditional grid of streets and avenues in cardinal directions. Apart from earlier river lot subdivisions, the 1912 Hudson’s Bay Land Subdivision broke this pattern during an optimistic boom time. Today its vestiges are barely legible, yet indelibly mark Edmonton with its peculiar diagonal avenues of Kingsway and Princess Elizabeth. Once perceived as a progressive departure, what remains today stand as an awkward testament to a bold plan compromised with shifting circumstance.

The Hudson’s Bay Land Subdivision of 1912

The City Beautiful Movement ‘flowered’ in Canada between 1910-1913, just as planning was being established here as a profession. The 1912 Hudson’s Bay survey created by Driscoll and Knight constituted 1000 acres and at the time was ‘the biggest and most valuable tract of land ever subdivided in the Dominion of Canada’.

As seen in following plans, the Hudson’s Bay Company sat idle with their land apportioned through the Dominion Land Survey, allowing an appreciation of its value over the booming decade. The Town of Edmonton began to surround the large undeveloped tract raising both ire and encouragement of city officials.

1882 Plan of Settlement – original river lots and parts of Dominion Land Survey at fringe

1882 Plan of Settlement – original river lots and parts of Dominion Land Survey at fringe

circa early 1900’s – subdivision south of Jasper Ave first of Hudson’s Bay development

circa early 1900’s – subdivision south of Jasper Ave first of Hudson’s Bay development

1905 – Driscoll’s Map of City of Edmonton. Land developing around remaining Hudson’s Bay reserve

1905 – Driscoll’s Map of City of Edmonton. Land developing around remaining Hudson’s Bay reserve

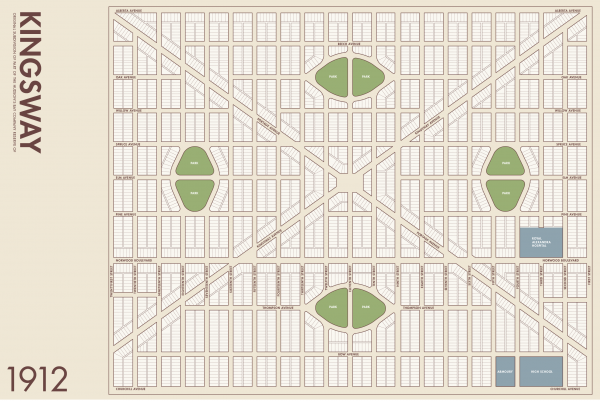

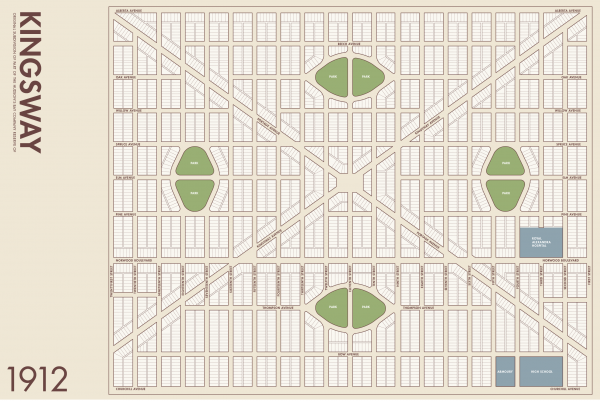

1912 Hudson’s Bay Subdivision Plan

1912 Hudson’s Bay Subdivision Plan

(Likely 1929) Map showing land sold on the Hudson’s Bay 1912 Subdivision and elsewhere as of that year. Revisions being made to subdivision per the markups and notes on this map.

(Likely 1929) Map showing land sold on the Hudson’s Bay 1912 Subdivision and elsewhere as of that year. Revisions being made to subdivision per the markups and notes on this map.

1954 – Most of the original 1912 subdivision has vanished

1954 – Most of the original 1912 subdivision has vanished

1957 Road Map solidifies the existence of much of present day layout of the area

1957 Road Map solidifies the existence of much of present day layout of the area

(excepting my redrafted 1912 plan) all images courtesy and copyright of City of Edmonton Archives and subject to conditions of use

Common City Beautiful plans of the era naturally emphasized beautification, the introduction of nature into the city, and landscaped boulevards and civic amenities. In addition to the over 45 acres of ‘artistically arranged’ parks, the plan spelled out some of today’s civic institutions including Royal Alexandria Hospital, Prince of Wales Armouries, and Victoria Composite High School. The diagonals were intended to be ceremonial boulevards, as highlighted by the use of Portage (now Kingsway) for a procession in 1939 Royal visits by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. The plan called for wide sidewalks on the diagonals and ‘more economical means of traffic to all quarters of the city‘.

The land lottery for the 1912 sale of the parcels triggered nothing short of a speculative frenzy during the unprecedented boom. Almost immediately after, Canada entered major economic depression in 1913 with winds of war blowing across from Europe. World War I, the Great Depression and an airport prevented the majority of the plan from ever being realized.

It’s tough to speculate whether the plan is an interesting footnote to the City’s urban history, or if there’s something meaningful to read in its realization. What is obvious is that Kingsway and Princess Elizabeth Avenues were intended to be endeared civic boulevards worthy of a Royal visit. The narrow parcels with their short sides oriented to the street along Kingsway, Portage, and Norwood suggest that they may have become interesting commercial avenues with varying facades; a similar condition seen of today’s Alberta Avenue or 124th Street.

The wedge shaped lots formed at non-orthogonal intersections is an ingredient in a loved ‘flatiron’ building typology built in many cities generally in the 20th Century:

It is difficult to speculate that following this plan stubbornly would have yielded an area today of great civic pride, but we do know that to be the plan’s original intention. The avenues were intended to be worthy of Royalty, but what exists today on much of Kingsway is unremarkable:

A blue collar city with a pattern of boom and bust economies has led to a development mentality that prioritizes expediency at the expense of long term vision and principles. Fear surrounds the perceived costs of inaction: we collectively understand that if a project isn’t completed now while conditions are favourable, it may never happen. The compromises we seem overly willing to make at times are the parallel – where standing by vision and principles during an idle circumstance seems to many as foolish and imprudent.

With the original subdivision of these HBC lands now over a century behind us, we’ve reached an historic parallel to perhaps stop and reflect upon. After more than a decade of meteoric rise we again face the looming prospect of a dark, lingering economic cloud. Can we stand by the visions and principles in our plans that we’ve forecast will lead us forward into the next 50-100 years? Or, as deficits replace surpluses, will we settle in the here and now for what is merely profitable?

References:

Meek, Margaret Anne. “History Of The City Beautiful Movement In Canada, 1890-1930”. University of British Columbia, 1978. Print.

Street Map Of The City Of Edmonton. Driscoll & Knight, 1924. Web. 4 Jan. 2016.

http://www.edmonton.ca/city_government/documents/PDF/EAM-34_FULL.pdf

Links:

https://classconnection.s3.amazonaws.com/238/flashcards/1219238/jpg/chicago_21334636969558.jpg

http://www.fredericklawolmsted.com/burnham.htm

Jason Pfeifer is an Edmonton based Landscape Architect and Urban Designer, and Principal of PD+A Studio, a boutique service-oriented interdisciplinary design firm.

2 comments

What is the city claiming copyright in? Those maps are long since in the public domain.

Most of the images I used in the gallery of the old maps of Edmonton are downloaded directly from the online portion of the archive, which has rights of use for downloading images.