Last week I wrote about how, after three years of volunteering with Dans la Rue, I came to see Berri Square as one of the few places where Montreal’s homeless and marginalized people find common ground with more fortunate Montrealers. I concluded by saying I believe that people who are visible will tend to be better citizens.

From Gotham City to Metropolis?

Yet it seems that many Montrealers want nothing more than to put the homeless out of sight and out of mind. Earlier this month, the mayor recommended shortening the Ste-Catherine pedestrian zone to exclude Berri Square from the seasonal festivities, citing police concerns about safety around Berri Square.

And last November, when Warner Brothers opened an studio in the tower on the East side of the park, the studio director compared Place Emilie-Gamelin to Gotham City, home to Batman and well-known for it’s dark atmosphere, crime, corruption and decay. Naturally, the studio announced that they hoped to make the neighbourhood “less like Gotham City and more like Metropolis,” Superman’s world-class city. And he was clear about the demographic change that would imply.

So on one hand they’re trying to keep festival-goers and terrace-hoppers away from Berri Square while on they other, they would push out the homeless and marginalized people who do use it.

This unwillingness to find common ground is even more shameful when you consider the 170-year-old tradition of providing help and resources to those in need at Berri Square.

A place for Montreal’s homeless since 1841.

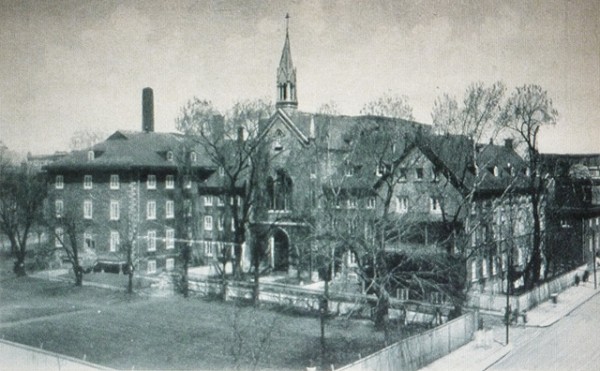

Montreal’s down and out laid claim to Berri Square long before the shops, hotels, bus station, university or even the church were established. In 1841 Emilie Gamelin founded a hospice called l’Asile de la Providence in the very same spot. Its main purpose was to provide sanctuary for elderly women, but the nuns who ran the charity also handed out hundreds of meals to the poor and homeless every day. In 1844, a wing was added along Ste-Catherine Street to house 50 orphans. But after 120 years of service, the hospice came under the developer’s axe: the City bought the land in 1962 and razed the building in order to excavate the Berri-UQAM metro terminal.

From Square to Parc to Quartier

The lot then sat empty until 1993 when it became Berri Square. and three years later, it renamed Emilie Gamelin Park. While the new name honoured Gamelin’s work with the poor, it hid a more subtle and far-reaching implication: as a park, the city was able to enforce a curfew in the space from midnight until 6am.

In protest, 250 punks and street kids camped out overnight in the square. A flyer promoting the demonstration read: “As the corporate monopoly on land continues to grow, our free public spaces become fewer and fewer…Such is the story of Berri Square. Once a place for all, now closed for business and open only to the well-groomed.” Riot police arrested 70 people and fined them for breaking the curfew, which still remains in place today.

A further bylaw in 2006 banned dogs from Parc Emilie-Gamelin and Viger Squares, which some interpret as a blatant message that street kids are unwelcome in these public spaces.

But there remained at least one occasion each year when the curfew was broken: ATSA’s annual État d’Urgence, a 3-day event that aimed to bring together homeless and the general public, in a festive atmosphere of free food, artistic performances, and urban camping. But in November 2011, the festival’s organizers wrote an open letter to Voir, explaining that they were unable to get funding to sustain the event:

Notre festival était un geste d’espoir, de création, de civisme, d’humanité. Mais le quartier change… il se nomme maintenant le Quartier des spectacles. Beaucoup d’argent y a été investi, mais l’ATSA, elle, n’a pas su en trouver pour pérenniser l’État d’urgence! On peut penser que l’argent est plus rare pour ceux qui proposent autre chose que du formaté «tourisme culturel».

État d’Urgence is an example of how programming a public space can be inclusive of more marginalized people (I blogged about the 2009 edition here). Sentier Urbain has created another inspiring model for shared public spaces. With Berri Square set to be revitalized beyond recognition, I argue that a common ground, where the homeless can be visible and find help when and if they want it, is part of our city’s heritage that is worth preserving.

4 comments

I can’t believe you wrote a whole article about Berri Square without mentioning that it’s also a rare safe space for another marginalized group in Canada: Gays. I guess the homeless aren’t the only people that Quebecers would rather have out-of-sight, out-of-mind.

The gay community is hardly out of sight out of mind in Montreal. Nor is Berri square a safe space for gays, or anyone else for that matter.

It’s a difficult situation.. while I advocate for the right of safe haven for homeless individuals in and around the downtown core, I’m not so sure that crack and meth and other addicts should be allowed to monopolize a busy downtown public park, which is essentially the situation now in Berri Square. It isn’t as haven for the homeless, it’s a haven for addicts, some (but not all) of whom are violent and emotionally unstable. I’m fairly open to all walks of life, and am generally not afraid to mingle with most people, Berri Square is the only public park on the entire island of Montreal that I refuse to walk through. It’s dirty, scary, and creepy.

That said, with government officials refusing to open safe injection sites, where else can drug users go? And with homeless shelters overcrowded with individuals who should be in hospitals and long term care facilities, facilities that do not exist, where are they to go, too?

What Montreal, and all cities need, is an outdoor camp providing basic amenities, monitored by health officials and law enforcement. Montreal also needs an appropriate long term care facility for low income individuals with emotional and physical health issues. There are group homes for abandoned youth and children, and old folks homes for abandoned elderly individuals. We need homes too for our abandoned middle aged individuals too. Weird the way we expect everyone between 18 and 65 to magically take care of themselves without any outside help or intervention. In any case..

We need to clean up Berri Square. It is, to sum it up in one word: GROSS.

Niomi, I think you draw a false dichotomy in the first half of your comment but you hit the nail on the head at the end. There is a growing body of research that reveals the concentration of social services in disadvantaged neighbourhoods is both bad for the people requiring services and for the neighbourhood itself. We need to stop writing Dickensian waffle that romanticizes modern day poverty and start pressuring the Government of Quebec to provide social services adequately and evenly across Montreal and the province.

In terms of both safety and concentration, I see the area as highly successful, actually, in dealing with these urban “problems” that exist the world over. In most cities, these areas are off to the side of downtown and used only by the homeless and the drug addicts — take Vancouver, where there is really no reason to go to the Downtown Eastside — its fringe is interesting, but its centre caters only to the down-and-outs.

Montréal’s equivalent offers so much more— the university, the library, the main métro station, an IGA at Place Dupuis, Archambault, the clubs and bars and restaurants along Sainte-Catherine, and it’s sandwiched between other popular destinations like the Village and the Latin Quarter — so in fact it is used day and night by so many ordinary people that it remains safe, despite what the studio director and Niomi say, who I’m willing to bet have never had any problems, just seen things they don’t like.

Our perception of safety and what is actually dangerous can be quite unrelated. I lived in the neighbourhood for 20 years, and I’m gay, too, and while it’s not crime-free and it’s not particularly pretty, it’s also not particularly dangerous — if you look at statistics, most violent crime happens between people who know each other, not between crackheads and innocent strangers walking through parks. Plus, if you go through Place Émilie-Gamelin often enough at different times of day, you get to see that it’s not only drug addicts and pushers who use it. But thank goodness they’re going to revitalize it. In terms of park design, it’s got quite a few problems of its own :)