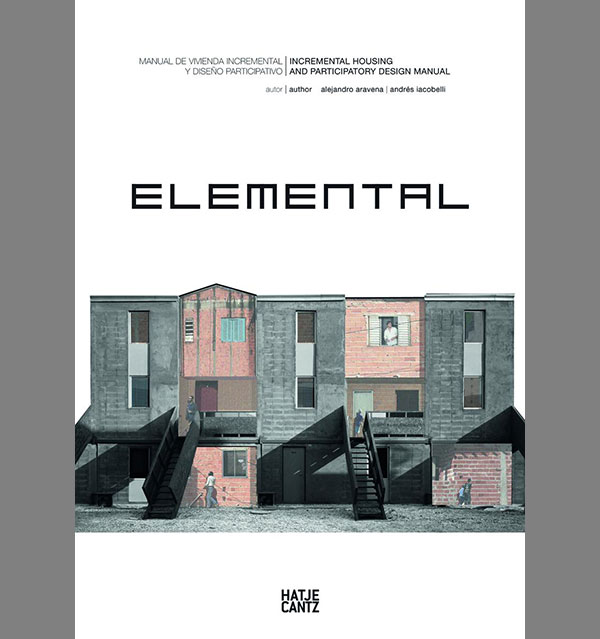

Author: Alejandro Aravena and Andrés Iacobelli (Hatje Cantz, 2013)

The creation of long term, socially sustainable, culturally appropriate housing is a challenge for architects, builders, planners and homeowners alike. This housing model demands maximum benefits using minimum resources. Such projects face some of the most challenging sets of demands over and above being plagued with insufficient funding and wavering political support. As the global urban population continues to skyrocket, the demand for social housing is also on the rise. In the words of the authors: “In order to provide an answer for urban growth that will occur from now to 2030 we must be able to build, in developing countries alone, one city for one million inhabitants per week with US$10,000 per unit in the best of cases.”

Within this context, Elemental: Incremental Housing and Participatory Design Manual comprehensively documents the work and design methodologies of Aravena and Iacobelli. Together, they make up Elemental, a Design Studio in Santiago, Chile, whose focus is the formulation of new solutions to this long-standing problem. This dual-language, 500+ page overview provides an in-depth look at, not only the portfolio of their creative partnership, but of their attitudes and approaches to the development of social housing.

A design typology called “incremental design” is the heart of Aravena and Iacobelli’s work. Definitions vary slightly around the world, but overall incremental design is a solution that was developed to provide new housing for communities of people living in informal settlements and aims to produce maximum benefits with minimum resources. Aravena and Iacobelli’s work aims to address the incredible challenges associated with an ever-increasing urban population, seeking solutions that will support urban populations to thrive, citing the many benefits of living within city limits.

The majority of book is dedicated to detailed case studies, but the early chapters provide a vibrant critical discussion of social housing practices today, beginning with an explanation of Elemental’s attitude and approach and of how their self-proclaimed “Do Tank” came to be. Aravena and Iacobelli do not claim to have one right answer to the problem of social housing. In fact, they claim that to progress towards real solutions, we need to have “a readiness to throw it all in the trash.” We need to consider ideas that may seem radical and we need to recognize when they are not the right solution for a particular context, and move on. With this in mind, their success is due to their willingness to look critically at their own processes and designs, and to use their mistakes and successes as design tools.

Quinta Monroy—a housing development in Iquique, Chile—is the first project in which Aravena and Iacobelli were able to test their theory of incremental design in the real world. Following the inception of the design team at Harvard and a series of architecture studios, design charrettes, critiques, and discussions, the development of Quinta Monroy began, turning ideas that had been evolving for over two years, into action.

Quinta Monroy was arguably a success in terms of completing a project type centered on new design approaches, new community participation methods, and new funding models. The book examines the process from initial conception to occupation, explicitly discussing political and social challenges of the project, such as working directly with community members who have little or no trust in the housing system, the difficulties of dismantling and relocating an entire community of over 100 families, and the incredible lack of funding.

The survey also explains the benefits of employing the skills and experiences of community members in design decision-making, which ensured that the team delivered homes appropriate for the community. The deep level of participation and commitment of the future homeowners and the architectural team is impressive and also daunting, leaving one wondering how universal the incremental design solution may be.

After the completion of Quinta Monroy, the project was criticized for its lack of adaptability to other times and places. In response, Elemental launched a worldwide design-build competition that aimed to provide similar housing solutions to seven different sites around Chile. In 2004, the winners were chosen and, surprisingly, four out of the seven projects were built and occupied by 2010. The remaining two unfinished projects made it as far as building permit approval.

For each project, Elemental provides descriptions of design, construction, and funding strategies as well as architectural drawings, photos and 3D images. Aravena and Iacobelli are candid about challenges they encountered along the way—many of them political—and about various design elements that were cut or added at the last minute. However, the discussion falls short in following up with the homeowners and other the stakeholders involved in each of the projects.

For Quinta Monroy, the team revisited the project eighteen months after occupation. However, it is hard to credit the team with full success without knowing how the developments have impacted the individuals and the communities over a longer period of time. Many of the houses are visible on Google Streetview and a quick walk-through can help to shed some light on how well (or how poorly) the projects succeeded.

However, to fully gauge the success of the projects, it might help to compare the long-term impacts of typical low-rise social housing types in North America to that of projects like Quinta Monroy. How do these projects fare over time? Does the incremental design component help or hinder the long-term success of the neighbouhood? Perhaps it would be beneficial for Elemental to review their projects one, five and ten years later, to see how the projects hold up as they transition through seasons, generations, and surrounding development.

Despite this lack of longer term evaluation of specific projects, Elemental seems to be refining their skills, with each new project building on the lessons of the last, and ultimately becoming more streamlined and architecturally pleasing. Elemental’s Lo Barnechea is an impressive feat when you compare the before and after.

Although incremental architecture as it is now may not be a final solution, the creative duo should be praised for pioneering a new approach to an old problem, for opening up the doors to criticism and dialogue by sharing their experiences and ideas so openly, and for giving the architecture industry a much-needed push towards finding better solutions to social housing challenges worldwide. And, this engaging book shares that journey with its readers.

***

Ellen Ziegler is currently living in Toronto where she is writing her masters thesis in Advanced Studies of Architecture. She spends most of her time biking, exploring the city, drinking coffee, and writing book reviews.