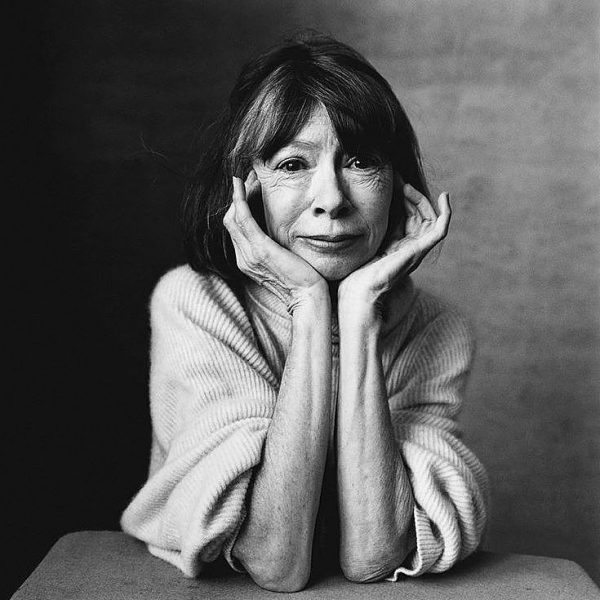

After a month of reading the essays of Joan Didion—the American author whose literary reputation seemed to ascend to new heights when she died late last year— I discovered something unexpected: Didion is a placemaker writer, a close observer and unsentimental celebrator of civic life, a fierce critic of sprawl and inequality, a defender of the freeway experience, and, briefly, a student of land economics. Didion is many things to many people, including now, to this reader, a secret urbanist from Cowtown, California.

It is hard to overstate Didion’s influence on her fellow writers. Host a confessional for prominent essayists and fiction writers from the last half century, and more than a few will acknowledge stealing from her. The DNA of her sentences—staccato lists and tumbling subordinate clauses—is as stunning as it is prolific. Simply count the number of tributes written in the wake of her passing. The New York Times alone published a half dozen articles about Didion in the span of a few weeks, the most recent a partial takedown by Daphne Merkin entitled “The Cult of St. Joan.” In spite of this and other sporadic attacks on her early conservatism, Didion is venerated to an extent that is unusual for a writer of any era, but particularly in our current fault-finding era.

When I say Didion is a placemaking writer, I mean that literally. Didion creates and then transforms the places she wrote about. Through observed physical fact and shared unsentimental anecdote, she puts the there, there. Didion wrote repeatedly about specific cities where she either lived or spent extended periods of time. In the pages of her essays, she visits and revisits the same locations, as if trying to make sense of them for herself and for us: Honolulu, Las Vegas, and especially California and New York City.

“New York,” she wrote in 1968, “was no mere city. It was instead an infinitely romantic notion, the mysterious nexus of all love and money and power, the shining and perishable dream itself.” The sentence is both a tribute and a takedown of a city that lives in all of our imaginations. More than two decades later, when confronting class and inequality in the case of the Central Park Five, she challenged other journalists and public opinion: “What is singular about New York, and remains virtually incomprehensible to people who live in less rigidly organized parts of the country, is the minimal level of comfort and opportunity its citizens have come to accept.”

For Didion, the naked city’s eight million stories were “all the same story, each devised to obscure not only the city’s actual tensions of race and class but also, more significantly, the civic and commercial arrangements that rendered those tensions irreconcilable.” What is remarkable about this essay (“Sentimental Journeys”) is how much of its analysis and commentary apply to the New York or Toronto of 2022, cities where inequality and structural racism are still the primary forces that disfigure urban life.

But her most moving writing about New York is the deeply personal, and less assured, “Goodbye to All That.” An essay in the true sense, it explores her changing and ambivalent relationship with New York without offering any crisp answers. It builds up the image of New York for the reader only to tear it down again, ruthlessly. Cities are never finished, just as Didion’s apprehension of New York was never static. In her purposefully wandering prose, she crystallizes what it means to be young and enthralled by a city that feels simultaneously at your fingertips and yet impossible to grasp:

…I was in love with New York. I do not mean “love” in any colloquial way, I mean that I was in love with the city, the way you love the first person who ever touches you and never love anyone quite that way again. I remember walking across Sixty-second Street one twilight that first spring, or the second spring, they were all alike for a while. I was late to meet someone but I stopped at Lexington Avenue and bought a peach and stood on the corner eating it and knew that I had come out of the West and reached the mirage. I could taste the peach and feel the soft air blowing from a subway grating on my legs and I could smell lilac and garbage and expensive perfume and I knew that it would cost something sooner or later—because I did not belong there, did not come from there—but when you are twenty-two or twenty-three, you figure that later you will have a high emotional balance, and be able to pay whatever it costs. I still believed in possibilities then, still had the sense, so peculiar to New York, that something extraordinary would happen any minute, any day, any month.

The shared anecdote brought to life with commonplace details and coolly observed facts amidst the limitless possibility of a larger-than-life city, its streets filled with smells, tastes, and articulated longings. This is how Didion makes the shape of a place flash brightly on the page. And though the spell cast on her by New York City would eventually be broken (because the city itself was broken and unliveable in so many ways), we get to linger on that street corner with the younger Didion because of the distinctiveness of her view.

Moving west to her native California, Didion wrote about Los Angeles as a city “largely conceived as a series of real estate promotions.” To truly understand mobility in the Los Angeles basin and its unbreakable connection to the autonomy of the car, one needed “to have participated in the freeway experience, which is [LA’s] only secular communion.” In “Bureaucrats,” Didion mocks the technocrats responsible for a doomed Caltrans pilot project for an HOV lane on the notorious Santa Monica Freeway. She pokes sarcastically at a planner fond of speaking in jargon and pulls a quote from Reyner Banham’s seminal book, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies. The reference to Banham alone credentials Didion as an urbanist, while the essay’s condescension—sometimes smacking of plain ridicule—gives ammunition to those who accuse her of elitism.

In much of her writing about the American West, Didion walks the line between cynicism and fondness, despair and nostalgia. There is a poignancy and shared familiarity to her perspective of San Francisco, Berkeley, Malibu, LA, Sacramento, the Central Valley. “A good part of any day in Los Angeles is spent driving, alone, through streets devoid of meaning to the driver, which is one reason the place exhilarates some people, and floods others with an amorphous unease,” she wrote in “Pacific Distances” (1979-1991). In the Haight-Ashbury counterculture, “we were seeing the desperate attempt of a handful of pathetically unequipped children to create a community in a social vacuum.” Describing runaway fires in the San Gabriel Mountains in the 1960s—another essay that feels like it could have been written now—she wrote: “The city burning is Los Angeles’s deepest image of itself.” Again, images of the city flash vividly on the page—from Day of the Locust and the Watts riots to Rodney King and the Getty Fire—illuminating memories for the reader of places they need not have ever visited.

Early in her career, while working at Vogue, Didion enrolled in an Urban Land Economics course, which she hoped to turn into a real estate play to fund her fiction writing. From the course readings on parking ratios and gross floor area, she spun gold, in the form of an opening paragraph on shopping centres:

They float on the landscape like pyramids to the boom years, all of those Plazas and Malls and Esplanades. All those Squares and Fairs. All those Towns and Dales, all those Villages, all those Forests and Parks and Lands. Stonestown. Hillsdale. Valley Fair, Mayfair, Northgate, Southgate, Eastgate, Westgate. Gulfgate. They are toy garden cities in which no one lives but everyone consumes, profound equalizers, the perfect fusion of the profit motive and the egalitarian ideal, and to hear their names is to recall words and phrases no longer quite current.

Didion’s opening paragraph from “On the Mall” (1975) shares a compelling intertextuality with the concluding paragraph from a talk Louis Kahn gave to the International Congresses of Modern Architecture in 1959:

I believe also that shopping centers in our country are not shopping centers—they are buying centers, that is all they are—and they can never develop into shopping centers, that is too wonderful a thing. They are devices for buying, that’s all. They are as stupid as anything when the cars are away. They look like some of the abandoned American West. You see nothing and more nothing in most of them.

I am not suggesting that Didion cribbed from or was even aware of Kahn’s speech, but it is certainly interesting that her thinking about shopping centres aligns so closely with one of the last great modern American architects. Kahnian comparisons notwithstanding, passages like the one above transmit the thrill of Didion’s exultation of language, celebrating words for their sounds, syntax, and semantic weight or weightlessness. In the same essay, she goes on to describe car-induced sprawl as if the “frontier had been reinvented, and its shape was the subdivision, that new free land on which all settlers could recast their lives tabula rasa.”

Unlike New York’s streetscapes or the burning of LA, here she is not so much making places come alive with the brilliance of light and language, but rather dulling them down to their antiseptic blandness. The false promises of post-war suburban sprawl, of growth paying for growth, of places “behind which there isn’t some historical imperative,” can’t compete with either the complex tensions of New York City or the regional mysteries of Los Angeles.

I have no idea whether Didion considered herself an urbanist writer. Probably not. What can be plainly found in her work, however, are the observations of a writer making both a subject and an object of place, a seeker who methodically and artfully constructs sense of whatever city, town, or neighbourhood she happens to visit. As Didion herself once told us: “I write entirely to find out what I’m thinking, what I’m looking at, what I see and what it means.”

photos by Alyssa L. Miller and Tradlands

Josh Fullan is the director of Maximum City, a public engagement and education firm based in Toronto