Property taxes are weird. They don’t work like other taxes. I’ve been trying to get my head around them for a few years now.

In the run-up to this year’s operating budget, which is going to council next week, I thought I’d try to figure them out. I started researching a story for NOW magazine about how the city works out property taxes. My research confirmed that I was not the only one who had difficulty sorting them out — even the experts I talked to weren’t confident about all the details. The one person who was really on top of them was Councillor Shelley Carroll, chair of the city’s budget committee.

NOW found the details of how property taxes worked too dry for a magazine article, perhaps understandably. They did publish parts of what I wrote in yesterday’s issue, but unfortunately, in the search for an interesting headline and the need to keep things tight, what’s left of the article doesn’t really hang together.

I’m hoping that Spacing‘s readers may be more interested in the gory details of the workings of the property tax system and its implications, so here goes.

Property taxes basically work backwards, compared to other taxes.

For most taxes, like sales or income, the government sets a fixed percentage that it will collect, and then sees what revenue comes in.

For property taxes, on the other hand, the city government sets the exact revenue it wants to collect, and then works out what percentage to charge each existing property to get that revenue.

There are several important implications to this backwards system, all of which cause difficulties to the city.

First, city revenues don’t increase automatically with inflation and growth. The provincial and federal governments get more money automatically from the same taxation rates most years, because prices and incomes have gone up, and there are more jobs and more sales. That’s why they seem to be able to both increase spending and cut taxes at the same time.

The city, by contrast, will get exactly the same amount of money each year from existing properties. There is not even any increase to compensate for inflation.

The only way the city can increase its revenue from existing properties is by increasing its revenue target. The media generally describes this as “raising taxes”.

Here again, the city is a victim of the backwards property tax system. For other types of taxes, “raising taxes” refers to increasing the percentage that the government collects. If we judged the city by this standard, Toronto would in fact be a tax-cutting juggernaut. Between 2002 and 2007, Toronto’s residential property tax rate dropped from 0.73081% of a property’s value to 0.5888434% — a cut of about 19%. Commercial taxes dropped by slightly more.

(The drop is because property values have increased quite a lot, much more than municipal spending. Quite a lot of properties in Toronto, whose values have increased slowly, have enjoyed a small reduction in the amount of money they pay in tax in recent years).

If we were to judge other levels of government by the amount of extra revenue they raise, we would find that they usually increase their revenue in absolute terms by 5% or more each year — far more than the City of Toronto has been doing. Yet they give the appearance of keeping taxes steady or cutting them, while cities are presented as raising taxes every year. It makes city governments look less competent, despite the fact the City of Toronto, for one, has actually been operating under much tighter fiscal constraints than upper levels of government.

The one way that city governments can get more money from property taxes without “raising” taxes is if more units are built. Revenue from new units becomes an addition to the existing property tax base, expanding it. That creates a temptation to accept as much development as possible in order to raise revenues without a “tax increase.” Of course, more units means there are more people who need more services, but a council desperate for money could overlook that problem.

When I talked to Shelley Carroll, she agreed that this temptation was a danger, especially in smaller councils where greenfield developments could bring in lots of money, but she felt that most Toronto councillors understood that it wouldn’t actually improve Toronto’s situation, and would not fall into that trap. I’m not entirely sure myself — while I have no doubt that most councillors are consciously aware of the trade-offs, I think that the unconscious bias is powerful, especially given that many downtown developments are not accompanied by huge increases in service like new police stations, so that the costs are more hidden. Intensification is good, of course, but the danger is that the need for new revenues will lead to ignoring planning considerations in order to build as many new units as possible, without expanding services to match.

(Note that even when new units are built, a mature city like Toronto probably won’t get revenue expansion that is equivalent to economic growth, because the new units are still a small percentage of the overall size of the city. The new units factor makes a much bigger difference to a small municipality.)

The fixed property tax system also, to some extent, insulates the city government from the state of existing neighbourhoods. Upper levels of government suffer if the economy is declining, or are rewarded with more revenue if the economy is doing well. But the city gets the same revenue whether neighbourhoods are improving or declining. This situation reduces the fiscal incentive for the city to try to make existing neighbourhoods better, or to try to do something about the problems of declining neighbourhoods. Overall, the result is that the property tax system tends to push a city in the direction of seeking new development rather than nurturing existing properties.

The final big problem with the property tax system is rhetorical. It gives an in-built advantage to right-wing tax cutters in public debate. City politicians who simply want to maintain services at existing levels have to “raise taxes” every year. By contrast, anti-government politicians can call for a reasonable-sounding and attractive “tax freeze,” which actually means cutting city revenues in real terms (because of inflation).

Such a promise helped Mel Lastman get elected mayor of the newly amalgamated Toronto in 1997, and his three years of tax freeze in the midst of amalgamation caused problems for the city’s budget that still have repercussions. In Ottawa’s 2006 municipal election, the progressive candidate lost his lead in the polls and eventually the election to a right-wing candidate promising a tax freeze.

The property tax system has these peculiarities because it’s one of the oldest forms of taxation around. It developed at a time when growth and inflation were fairly slow, and when municipalities had fairly small populations and provided limited, predictable services.

Property taxes were also shaped by the subordination of municipal governments to the province. For a long time, the province has imposed a rule that municipal governments are not allowed to budget for either deficits or surpluses [clarification – in their operating budget. They can borrow for the capital budget]. (That’s another reason why local governments are required to set revenue targets for the tax, rather than seeing what the economy brings in — they need to be exact in their projections).

But, as Carroll says, “the original design doesn’t match up with today’s reality.”

Cities now have much greater responsibilities than they did in the past, including social services whose costs fluctuate with the economy, and large capital projects. And once a city gets to a certain size, these responsibilities begin to expand rapidly. Carroll explains that most cities start to look for new sources of revenue that grow with the economy as they approach a population of a million. By three million, cities cannot really function without alternative revenue sources. This need is why Toronto’s city council introduced the land transfer tax last year.

I have to wonder, though, if we shouldn’t also look at modernizing the property tax system itself so that property tax revenues grow with inflation and the economy. It’s tricky, but I think there are ways to do it. The second part of my NOW article deals with that, and, while there’s a section that doesn’t quite make sense because of cuts, I refer readers to it if they are interested. This post has gone on long enough for even the most patient Spacing reader.

photo by Trea Brown

16 comments

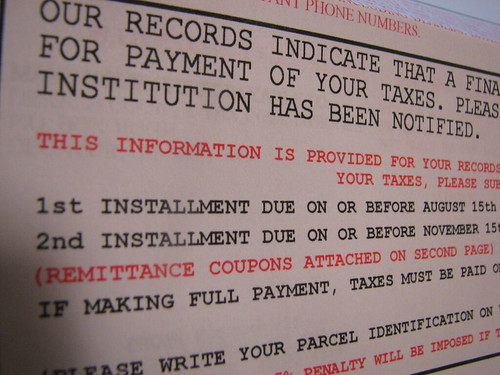

I actually found this article quite interesting. Especially given that I just bought my first home and received my first property tax bill. Nice to have some understanding of what’s going on there.

Thanks – a helpful explanation.

There’s a further detail that could help though I miss the full import – there’s a division between the tax on the building and the tax on the land. Some – eg. Greens suggest upping the tax on the land as improvements and maintenance on buildings boost taxes and help ease the conversion of old buildings to parking lots as vacant land in urban core areas is less “valuable”.

Maybe we need a new category of tax for the city – a tax on paved car space – including city streets and public sector parking lots. But we don’t want to tax the cars – they vote.

And what an under-statement – “a council desperate for money could overlook this problem” of okaying excessive devilopment for the money!!, though the OMB is also a big part of the problem.

Re: “a council desperate for money could overlook this problem” of okaying excessive development for the money.”

What an understatement indeed. I am not anti-development but it strikes me as more than just a coicidence that the unprecedented condo boom in our City (which still seems to be full steam ahead) started happening post-amalgamation… seems the development fees became a key “revenue tool” for the City offsetting any decreased funding from Queen’s Park. And darn it if the bulk of this condo boom hasn’t taken place while a supposedly “progressive” council has been in power. (quotation marks used because, frankly, I think this council is progressive in appearance only).

Also interesting to note that on top of amalgamation (which saw a marked reduction in the number of elected municipal officials in Toronto — and hence marked reduction in the ability of local constituents to make their voices heard), the City of Toronto Act gave the City increased new powers which have even further diminished the ability of local residents to help shape new developments in their area.

The City often likes to point to a few high profile cases and lay the blame for this at the feet of the OMB. The OMB may be a factor in some cases. But the lion’s share of the responsibility rests with the City, it’s official plan, and the reduced powers of residents to help shape new developments in their community.

Thanks for the insightful article. It confirms what I have suspected for a while, and definately puts things in perspective.

An excellent summary of how it all fits together. Thanks very much for posting. I’d hope that NOW is underestimating its readership if they think that people wouldn’t be interested in this: it’s essential knowledge for thinking about how our city works…

Thanks again.

“For most taxes, like sales or income, the government sets a fixed percentage that it will collect, and then sees what revenue comes in.”

That’s not really the way it works. The provincial/federal governments set their tax rates (income/sales/etc.) with a pretty good idea of what the revenue will be. They have a pretty good idea of the size of the tax base, and they set the rates so that revenues will match expenditures (as best they can).

-Josh

We shouldn’t raise property taxes because the value has gone up, the money is only on paper and isn’t realized until you sell or remortgage.

I can see raising taxes if you’re getting an income from it, but that mean rents will need to escalate – that won’t sell.

It is a weird system.

It’s time to do away with the property tax or have a minimum base tax. The rest should be raised with a carbon tax or consumption fees.

Dylan, you and councillor Carrol wisely point out that new development does not directly equate to increased revenue for the city.

In the current tax / expenditure climate, the city spends on average $ 8,282.00 per year per household. On average it receives $ 2,176 per household in property taxes. The city also receives approx. $2,318.96 in revenue (per household) from other sources like fees and provincial transfers. This still leaves a deficit of $3,787 per year per household. That difference is largely made up from the taxation of the non-residential class. This is why Toronto finds itself in a precarious position. Where can it find the money to make up the shortfall? Or will existing residents accept a dilution of services?

Before it was easy to rely on the contributions of the non residential class. Now though the onerous tax burden that has been placed on the non residential property class has created stagnation within it. We have already witnessed Toronto’s pathetic (negative) record on job creation over the booming past decade. Between 2000 and 2006, slightly over 14 million s.f. of office space has been developed across the GTA with the overwhelming majority (90%) taking place in suburbs. Mississauga itself, while being less than half the size of Toronto, had five times the amount.

As I posted about in my blog. They city is lucky it missed its growth targets. If they city had grown by the projected amount of 131,966 it would be $195,982,448 worse off than it already is.

http://southofsteeles.blogspot.com/2008/01/toronto-cannot-afford-to-grow.html

Thank you for posting this.

The NOW version illustrates why I can’t read it. I don’t think they respect their readers, everything becomes shrill. “The great crane robbery.” Somebody said it once, they are the Sun of the left, nothing more.

People are smarter than both those papers.

It seems to me that it is odd that in this discussion the only time there is a mention of the province is in talking about deficits and surpluses because, really, the entire property tax system is regulated by your MPs at Queens Park!

First, in regard to deficits and surpluses. It should be clarified that this is for operating budgets only. Municipalities have a capital budget as well. The capital budget can run in deficit but the payments on that debt are covered through the operating budget. Therefor if a municipality commits to spending a lot of money on capital investments in a given year it will increase the operating budget for next year to service that debt. That is how municipalities can run ‘deficits’. That debt service becomes part of the operating budget municipal governments can then say they don’t have control over.

Secondly, someone made a comment about not raising property taxes because the assessment goes up. The city has not raised your taxes in this case. The tax rate is set by the city (an increase in the tax rate is an increase in property taxes, an increase in assessment is not technically a tax increase). Assessment is not controlled by the city! This is an important fact. MPAC, the Municipal Property Assessment Corporation, is a provincial agency and is responsible for tax assessments. Municipalities themselves have no control over how your property is assessed.

Lastly, it is my understanding that the property tax assessments had been frozen a number of times by various provincial governments and the entire assessment program is all out of whack making the system even more confusing and introducing many inequalities.

The Institute for Municipal Finance and Governance has lots of papers that might be of use to anyone interested in learning more on this topic:

http://www.utoronto.ca/mcis/imfg/resources.htm

Thanks Iain. I didn’t want to go into to the province and MPAC because that would have been even more complicated (technically, it’s actually MPAC that sets the tax rate, once the city has indicated its revenue target). But it’s valuable additional information. Similarly, Josh, I was keeping things simple to highlight the contrast. (Most taxes: rate fixed, revenue fluctuates; property taxes: revenue fixed, rates fluctuate).

Also, people talk about the province’s role quite a lot, and the various problems with assessment, but I’ve always found that people don’t go into the basics of how the taxes actually get calculated. I was really happy I got a chance to finally work it out – I’m glad others have found it useful too.

The property tax ought to be abolished, and replaced by a municipal income tax (which might apply to non-residents who work in the city as well). An income tax is progressive unlike the property tax; it does not put a high tax burden on the poor (who pay the property tax through their rent) or seniors who own their home but have low incomes. Furthermore, the complexities and imprecision of property tax assessments are eliminated, as is the link with fluctuating property values. If the municipal income tax is calculated on the provincial income tax forms, it would be very easy to collect.

Hi Dylan, sorry, I didn’t mean to criticise, just add. I think it was a great post : )

yes indeed it is a complicated system and it is true the general public is confused by the provincial assessment system and how it relates to taxes.But in the end people only really see the “total” tacxes and service charges that they pay at the end of the year and then decide if the taxes were fair or not.In the meantime new charges are being added to the water bills and “side service fees” are just being thrown at the public.Not to mention the new parking fines and fees that are in full effect.No wonder the confused public doesn’t know who to trust.They are told that if they want to preserve services they have to pay,then those services are cut and they have to pay more.I feel sorry for taxpayers they can’t seem to win at all.Maybe another article could explain the role the auditor-general plays in all this.

Iain – I meant the thanks sincerely! I did think about adding stuff about the province and MPAC but it just seemed too long – so it’s good to have the context added. Also, the capital budget context is important, too.

Via The Toronto Star

How much property tax will you pay?

http://www.thestar.com/News/GTA/article/407339

Calculator: (NB. does not include education portion)

http://www.thestar.com/article/349083