In this series on the different options for raising the $2 billion/year needed to pay for new transit in the GTHA, I am starting with the idea of a parking tax because it is probably the option that has most often been proposed by politicians, including those on the right.

The idea would be a charge a levy to commercial property owners (e.g. malls, offices) for each parking spot on their property. They would presumably pass this cost on to their customers/staff in some manner.

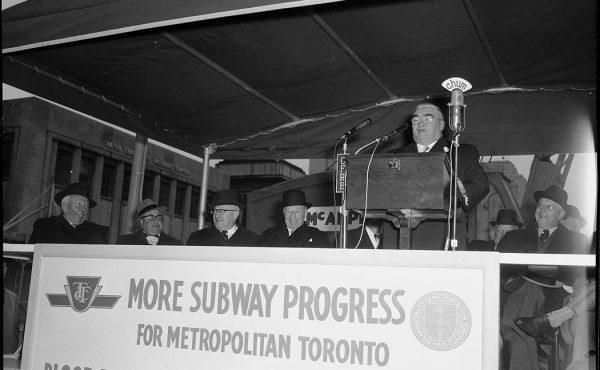

Even Mayor Rob Ford himself briefly opened the door to the idea of a parking tax to fund his Sheppard subway proposal (before quickly backing down). Budget chief Mike Del Grande also flirted with the idea. In John Michael McGrath’s article in the new issue of Spacing, councillor Peter Milczyn is quoted as noting the advantages of such a tax.

A levy on commercial parking spots to fund The Big Move would need to be significantly larger than what they had in mind, of course.

Amount charged

The CivicAction report (PDF) estimates that a dollar-a-day levy on commercial parking spots in the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Region would raise $1 billion a year.

Cost to implement

Rating: Good, but …

The cost to manage a commercial parking levy shouldn’t be onerous. The amount could be charged through the property tax system, with municipalities collecting it and passing it on to Metrolinx.

However, municipalities or Metrolinx would face one up-front cost because they would need to build an exact inventory of parking spaces on each commercial property across the city. Cities do not currently have such an inventory, but they ought to have one in order to do coherent transportation planning. So pushing them to do so is an added advantage, although it does create an initial cost.

Retail malls, paid parking lots, and many corporate headquarters already know how many parking spots they have, but factories and business parks may have more informal parking lots so there would be some work required coming up with an assessment system for such cases.

Behaviour incentives

Rating: Good, but …

A parking levy works as a pretty good indirect tracker of road use — if you drive somewhere, you usually need to park at your destination. So a parking levy can provide a useful nudge towards using another mode of transportation.

However, its effectiveness on driving behaviour would depend on how property owners pass it on to their customers. Where parking is already paid for, a small increase would cover the cost. For employers, it would be easy to pass the cost on to their staff, which would encourage staff to explore alternative modes of commuting.

For retail parking that is currently free, however, property owners would have a choice between changing their free parking to cost-based parking (which could entail some adaptation costs) or absorbing the costs through raised prices in stores or other means. If the costs are absorbed, then the positive impact on driver behaviour would be largely eliminated in these cases (since people would pay the cost no matter how they got there).

A parking levy also provides an incentive to landowners and developers not to create more parking spaces than they really need. As Donald Shoup has famously shown (PDF), free parking creates a lot of hidden costs. In turn, less parking available further encourages people to reconsider driving as an option.

However, the GTHA municipalities would, in turn, have to re-examine their minimum parking requirements for all buildings, since these would now impose ongoing costs to the owners. This re-examination should be done anyway, since these regulations often require unproductive and unneeded parking spaces, so this would also be a positive behaviour change.

At the same time, municipalities would want to consider some kind of incentive program to make it easier for landowners to remove unneeded parking spaces and replace them with something that contributes to the city (e.g. trees; bioswales to manage water runoff and provide green space; improved pedestrian access; bike parking). Some of the revenues from the parking levy might be diverted to cost-sharing for this purpose.

The negative behaviour associated with a parking levy is looking for free parking on nearby residential streets. In parts of town where main street parking is already charged, communities are already habituated to this issue, and experience has shown people still use the pay parking. In areas where a lot of free parking is currently available, businesses may choose to absorb the cost. If not, the charge for parking to cover the levy would be low (since the cost is only $1 a day per spot). In these areas, residential areas are often an inconvenient distance from destinations in any case. So this behaviour change may not be as significant as feared. It may be, however, that municipalities will need to review parking regulations on residential streets in suburban areas.

The other negative behaviour associated with a parking levy is sending drivers outside its bounds in search of destinations with free parking. This impact would be greatly reduced if the entire GTHA was subject to the levy, because most people would have to drive a great distance to escape it and there are fewer alternative destinations outside the GTHA. It would also be minimized because the daily rate is low, so the impact would be minimal on any individual driver and less likely to be worth the extra effort.

Political viability

Rating: Good

As noted above, a parking levy has had support even from conservative politicians. The idea of paying for parking is something people are used to. It is administratively simple and, given the low charge-per-day, the costs per person are not all that significant.

The most significant opposition would come from property owners who currently offer free parking, who could see a significant increase in the costs they pay on their property and would need to figure out some way to cover these new costs.

Another source of opposition could be suburban residential communities near commercial properties who fear an influx of drivers seeking free parking. This would not be an issue if retailers absorbed the cost, and would not likely be an issue if the cost remains low.

What do our readers think of this option? What are other advantages or disadvantages to a commercial parking levy?

(Note: as many of our readers know more about aspects of these issues than I do, I am also hoping that some crowdsourcing will happen in the comments section in terms of links and resources on each option).

Tomorrow: Highway Tolls

12 comments

“So a parking levy can provide a useful nudge towards using another mode of transportation”

Many of those who write about transportation issues fail to grasp reality. Am I going to take public transportation to the supermarket with my infant son because free parking is no longer offered? Of course not! While many choose to live in the city of Toronto without a car that is a not a real option for the rest of us.

Andrew: Just because it doesn’t apply to you, it doesn’t mean that it doesn’t apply to others. Those without kids, who could take transit if they just “decided to”, are the ones that it applies to. Stand on an overpass over the Gardiner and count the number of single-passenger cars passing beneath you… a reasonable proportion of those people are candidates for taking transit, and those are the people that the parking levy is ideally targeting.

Personally, I think the only way to get people to change their mind is to make transit the substantially cheaper option. If you have a highway toll and a parking levy put in place and all of a sudden it costs $100 more per month to drive a car to work, you might think long and hard about whether or not you need to drive. More people will start taking transit, which will ideally mean more revenue that can be turned into service improvements, and then transit becomes the cheaper AND better way and both transit-users and drivers benefit. When the tide comes in, all the boats go up…

I have to agree with Andrew. Behaviour is directly linked to where you live, and I don’t think it’s possible to change that. In the eight years I lived in Pickering, I never left my house without getting into my car, no matter what I was doing or where I was going. Here in Toronto, I rarely use my car even if I’m going somewhere like a grocery store, because trying to find parking on streets like Danforth or Queen is simply not worth the hassle. I’d rather take a granny cart or stroller to help me lug my groceries and kids home than put up with the hassle of driving a few blocks and searching for limited parking. Whether that parking is free or not makes no difference to me, both in Pickering and Toronto.

Free parking is an incentive to use a car. Fee parking should encouraged to reduce the requirement to use a car and use public transit instead.

Why just commercial? Residential should be included also.

I would also add in a 25 cent surcharge for the use of Drive-Thru’s.

Leo – that’s interesting – it sounds like it’s the availability of parking, rather than the cost, that is playing a role in deciding whether to use a car (distance is no doubt a factor as well).

Andrew,

I predict that you will be taking your infant son shopping using car-free transportation when that is the fastest, easiest and most convenient way of doing so.

Millions of babies life in urban car-free zones around the world. To see them, you don’t even have to travel to The Netherlands, just the Toronto Islands.

Here is a video of how they do it in Japan:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Iaz_T89wJ2o

And yes, some also blog about their experiences. Here’s one example:

http://mamabicycle.blogspot.ca/

Get the impression that it is not a big deal?

A parking tax levied to property owners, could in fact simply be passed on, the way other parking costs are passed on. Take for example Yorkdale Mall, it has a parking area about 3 times the size of the building. The mall passes the cost of owning and maintaining this asphalt ocean on to the stores, through their rent, the stores then pass this on to their customers through product prices. Even if you add a parking tax, the mall may pass that on through store rents, the stores then pass it on through prices, and whether you use that parking lot or not, your paying for it.

People who argue you need a car because you have to do shopping with an infant, haven’t be outside of car centric North America. What people in other places do, is shop more often. It’s not uncommon in Europe to buy what you need for the next 24 hours, every day. Stick your parcel on the shelf under the stroller and continue the trip home.

In the downtown area where I live, many people drive downtown, park on residential streets and take TTC the rest of the way. That’s very nice for them, but a real nuisance for those of us who pay for on-street parking but sometimes have difficulty finding a place to park. For some reason, parking west of Parliament has a one hour limit, but east of Parliament there is no limit (other than permit parking restrictions).

If retail areas are charged for parking, then they must be allowed to reduce the amount of parking provide. Currently malls have to provide large amounts of parking, but if they can show that (say) 10% are arriving by transit, they should be able to reduce their parking by 10%. (Most mall operators would love to do this, because then they can covert the space into rentable space)

@David: “For some reason, parking west of Parliament has a one hour limit, but east of Parliament there is no limit (other than permit parking restrictions).” Not true. There are ‘defaults’ on roads within the city that apply when there are no signs that override those defaults: speed is 50 km/h, roads are two-way, and parking is limited to THREE hours.